Final Fantasy Legend II – Save the World

If The Final Fantasy Legend was the blueprint, the rough draft, the demo; Final Fantasy Legend II is the genuine article, the “real McCoy” as they say. Dropping “The” from the Western title wasn’t the only improvement here; from the gameplay systems to the presentation and music, everything is turned up to eleven on a dial that goes to five. Playing Final Fantasy Legend II feels like a grand adventure whereas The Final Fantasy Legend feels like a series of set pieces with RPG coating designed only to showcase cool ideas to a board of lifeless corporate executives who cheat on their spouses every other night because they lack real passion for anything other than the almighty dollar; a harsh hyperbolical, I know, but a necessary one to illustrate just how much better this game truly is over its predecessor.

After the roaring success of The Final Fantasy Legend on the Game Boy, being the first Square game to ship over 1 million units, it was only natural to make a follow up. That follow up is the brilliant SaGa 2: Hihou Densetsu (translated to SaGa 2: Goddess of Destiny), or Final Fantasy Legend II in the West. Akitoshi Kawazu takes up the mantle once more as director and main designer; bringing along the original SaGa graphic designer, Katsutoshi Fujioka, and composer, Nobuo Uematsu, along with a second composer, Kenji Ito. The stars aligned at the precise point in spacetime to create a blinding constellation of pure talent culminating in the supernova known as Final Fantasy Legend II; much like Synchronicity-era Sting or Richard Dean Anderson’s haircut in Season 6 of MacGyver, if you don’t immediately see the appeal then there’s something wrong with you.

*Sting, Japanese SaGa 2 box art, and Richard Dean Anderson

*Sting, Japanese SaGa 2 box art, and Richard Dean Anderson

Immediately upon starting a new game, it becomes apparent that the presentation of Final Fantasy Legend II is of a much higher caliber than its predecessor; likely due to more experience developing for the hardware and a higher overall budget. The presentation is such an upgrade that it often feels like playing a modern demake of a newer role-playing game. Every tile seems to contain twice the detail of what may be found in the first game. Particularly notable is the use of blacks for shading, adding considerable depth to scenes that would have fallen flat in the previous title. These improvements make exploring the various sci-fantasy worlds optically interesting and visually spellbinding.

Although existing in a separate universe, Final Fantasy Legend II’s setting builds upon the foundation established in the first game, incorporating a compelling blend of sci-fi and fantasy elements across multiple worlds. These worlds span from sprawling futuristic cities governed by the Goddess Venus, where only the beautiful may live, to an abandoned realm of giants, where the giants have shrunk themselves to coexist with humans on another planet. Even Edo period Japan makes an appearance, featuring an amusing localization quirk replacing all mentions of the drug “opium” with “bananas”, courtesy of Nintendo of America’s family-friendly guidelines. Even the dungeons are memorable: one taking you inside a human body, while another features horrific faces all over the walls, inspired by horror mangaka Kazuo Umezu. Progression through these worlds often requires revisiting previous worlds, which makes the game feel like a large interconnected universe rather than a series of set pieces.

*Dungeon scene, notice the shadows on the columns and general sense of depth

*Dungeon scene, notice the shadows on the columns and general sense of depth

Compared to The Final Fantasy Legend, the plot is more detailed and emotional, with glimpses of humor sprinkled throughout. Our heroes are traveling the universe in search of the main character’s father, an adventurer on a quest to collect all of the sacred ‘magi’ stones to prevent them from falling into the wrong hands, even though they already have. Along the way, you encounter god-like beings, some based on mythological figures like Apollo, Venus, Ashura, and Odin, who were once ordinary people but gained power by hoarding magi. Each of these beings lusts for control over the universe and, of course, it falls on you to stop them and save the world.

Composers Nobuo Uematsu and Kenji Ito create an astounding soundtrack that perfectly compliments the Final Fantasy Legend II’s unique setting and consistently odd situations; containing some of the best music ever produced for the limited four channel Game Boy sound chip, including the brilliant final battle theme, “Save the World” – one of Nobuo Uematsu’s best works; if you haven’t heard it, stop reading this article and go do that instead.

Kenji Ito was brought on as the second composer to ease Uematsu’s workload, as the latter was also working on the music for Final Fantasy IV at the time. Ito’s output impressed the executives at Square, who couldn’t discern between an Uematsu track and an Ito track during production, resulting in Kenji Ito emerging as a prominent composer for Square moving forward, eventually becoming the primary composer for the SaGa series. This is especially impressive as Final Fantasy Legend II was the first computer game Kenji Ito worked on.

*Dungeon scene, notice the shadows on the columns and general sense of depth

*Dungeon scene, notice the shadows on the columns and general sense of depth

Voted Nintendo Power’s hardest game of 1990, Final Fantasy Legend II can ruin your day about as much as getting stabbed on the subway. That’s in spite of all the “casual” changes over its predecessor, such as the removal of permadeath, multiple save slots so you don’t get locked into game breaking death loops, and the ability to restart a battle after a full party wipe; the latter made possible by Odin, of Norse mythology, who resurrects the party personally so he can one day do battle with our heroes. In a cool bit of continuity, defeating Odin removes the resurrection feature entirely, sending you to the title screen upon death for the remainder of the game.

In a mechanic unique to SaGa 2, the magi that Odin and others use to make themselves so powerful is not exclusive to the Gods. Our heroes find magi throughout the game and can equip them to receive a number of useful effects, such as significant stat increases, powerful attacks, and even utility options like teleportation. By the end of the game, you’ve slain so many Gods and taken so much of their magi that you might start feeling like a God yourself. However, after a certain event, all the magi you’ve grown so accustomed to are stripped from you, leaving you like Alucard at the beginning of Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, a computer game trope that I appreciate, especially when it happens very late in a game as opposed to the beginning.

If some of these changes offend your hardcore sensibilities, worry not because the creators of Final Fantasy Legend II were acutely aware of this sentiment and ramped up the difficulty considerably to (over)compensate. Without changing any of the core gameplay mechanics from the first SaGa, battles are now deadly turn-based chess matches that can take a devastating turn with just one wrong move. This legendary difficulty is primarily accomplished by the game constantly throwing packs of fifteen or more monsters at you, requiring you to know your enemy and carefully plan every action to survive. This makes random encounters far more dangerous than most boss battles. In contrast, SaGa 1 was mostly a ‘hold A to win’ affair, making SaGa 2 feel far more strategic and fully realized than its older brother, albeit more frustrating at times.

*A battle scene resulting in death, watch to the end to see a brief glimpse of Odin reviving the party

*A battle scene resulting in death, watch to the end to see a brief glimpse of Odin reviving the party

As an additional compromise for the game’s high difficulty, running from battles is now much easier, to the point where it tempts abuse. While running isn’t useful early on, it becomes extremely helpful late game when skilling up is less important, especially when exploring large dungeons where you need to conserve your resources for bosses; in this way, the game encourages running, which is unfortunate because Final Fantasy Legend II is a role-playing game, not Sonic the Hedgehog 3 & Knuckles.

With permadeath now a thing of the past, guilds are no longer necessary for recruiting new party members. Instead, you create a party of four heroes at the start of the game by choosing between four races; one race being a new addition to the series; move over, Tetsuya Takahashi – we’ve got robots.

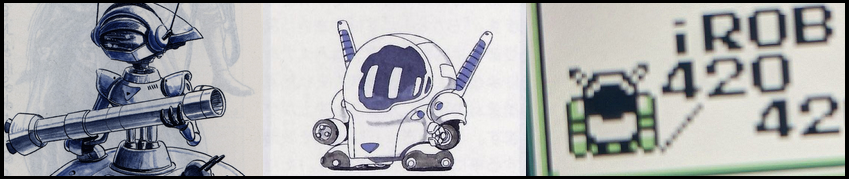

Continuing SaGa’s tradition of general weirdness, robots have a unique progression system that forgoes skilling up through battle in favor of an equipment-based system that increases your robot’s stats based on the armor they wear. This results in slower overall progression when compared to other races. Additionally, due to their reliance on armor for stat growth, robots have limited inventory space for weapons, and any weapon they do equip has its ammo cut in half. These drawbacks are partially mitigated by the fact that robots do not deplete weapons like other races; instead, they recharge by resting at an inn. These quirks ultimately result in a suboptimal party member that, despite the “rule of cool” dictating you include at least one in your party, is outclassed by every other race.

*Robots as portrayed in the NA game manual, the Japanese manual, and the actual game

*Robots as portrayed in the NA game manual, the Japanese manual, and the actual game

Humans, on the other hand, received a buff compared to their counterparts in SaGa 1, as chugging potion is no longer the only method to enhance their stats. They now skill up through normal battle, similar to mutants but with significantly faster progression, compensating for their lack of proficiency in magic. Similar to SaGa 1, humans excel at physical combat and serve as perfect frontline fighters, now even more so.

Mutants received a slight nerf from SaGa 1, where they were far too overpowered, resulting in a slower rate of stat progression. They still possess the unique ability to learn spells from battle, although the intricacies of this process still remain a mystery, and there is still a risk of overwriting previously acquired spells, a point of criticism left over from the first game; however, I have come to accept this quirk as an inherent part of mutant lore. Interestingly, there appears to be a way to permanently retain specific spells on mutant characters; yet, in typical SaGa fashion, the exact method to achieve this remains unexplained.

The monster race is still present and remains unchanged from SaGa 1. Monsters are total garbage unless you utilize an online guide to obtain the best monster type, a method not readily available to the typical ’90s kid. This emphasizes a significant point of contention that applies to all SaGa games: a lack of adequate explanation for the game’s systems, something SaGa fans just learn to get used to.

Outside of the four main party members, SaGa 2 includes several fully playable guest characters that join your party for brief periods as dictated by the story. Being a game that is more character-driven than its predecessor, guests joining is a frequent occurrence, and these guests vary in strength from overpowered to completely useless. This aspect can be seen as a precursor to the guest system in Final Fantasy XII, another game Akitoshi Kawazu worked on in a producer role.

*Our hero with two guest party members in Edo

*Our hero with two guest party members in Edo

The creators of SaGa 2: Hihou Densetsu insisted that the retail box be larger than any other Game Boy game box at the time of its release in 1990. This effort was made to make the game more noticeable to Japanese consumers as they browsed their local computer game stores. Like the big box it came in, SaGa 2 had big shoes to fill, and it did so in spectacular fashion. If young Richard Dean Anderson is the peak ’90s action celebrity, then Final Fantasy Legend II is the peak ’90s role-playing computer game for the Game Boy. Yes, I realize the oddly niche nature of this comparison; however, it requires someone with exceptionally good taste to understand, much like the SaGa series itself.

Final Fantasy Legend II builds upon the blueprint laid out by The Final Fantasy Legend, incorporating a plethora of improvements that culminate in a truly must-play game for the Game Boy. Its art direction, music, difficult gameplay, and overall green-charm leave an immediate imprint on the brain, potentially evoking a sense of nostalgia even if you’re experiencing it for the first time in your thirties (like myself).

Frequently brilliant and never boring. Radiant and refined in its execution. If you’re going to play just one Game Boy SaGa game, make it this one. Save the world.

As always, if you get bored, do something else.

(originally published on 5/21/2023)