Final Fantasy Legend III – Now Featuring Chrono Trigger

I. Prelude to Pedantry

Final Fantasy Legend III is a computer game. It possesses computer-game-like qualities and does things typically associated with computer games. It contains some of the same tropes one might expect to find in computer games, particularly ones of the role-playing variety and especially those released on the Game Boy in the ’90s; complete with green-tint and bite-sized gameplay best characterized as “bite-sized gameplay”, something I can’t (won’t) extrapolate on in this paragraph.

If it seems like I’m biding my time or beating around the bush, that may (or may not) be because I am. Maybe I just want to drink wine and play something that distracts me to the point where I don’t think about my mortgage, or maybe I simply don’t want to write about Final Fantasy Legend III. This mystery, and more, will be explored in detail throughout this collection of words – if I feel like it. Maybe I will gloss over the existential crisis bit entirely, maybe I won’t. Maybe I’ll gaslight you into believing that I never mentioned it at all, a magical feat considering the words are right here in all their (faded) glory. Either way, you will get what you came for, an article of some sort about a niche computer game for the Game Boy.

Developed by Square and released in 1991 in Japan as The Ruler of Time and Space ~ SaGa3 [Final Chapter], and released in North America two years later as Final Fantasy Legend III; the same year as Haddaway’s hit song ‘What is Love’ and William Gibson’s novel ‘Virtual Light,’ both completely unrelated; although Gibson could be credited with a modicum of influence on the SaGa series with his cyberpunk-grandfathery, and ‘What is Love’ is a funny, if overplayed, song that personifies going to the movies with your parents in ’93, perhaps with a Game Boy in the backseat, perhaps with Final Fantasy Legend III inserted in the cartridge slot of that Game Boy, and perhaps with your parents arguing about stopping at the Dollar Store for candy before heading to the theater. Whatever the case, it’s more likely you wanted to stay home since Gunstar Heroes was released that same year, and you would rather just play some Funstar (not a typo).

*Penguin publishing cover art for William Gibson’s “Virtual Light”, SaGa 3 box art, Red from Gunstar Heroes and Haddaway’s “What is Love” single

*Penguin publishing cover art for William Gibson’s “Virtual Light”, SaGa 3 box art, Red from Gunstar Heroes and Haddaway’s “What is Love” single

Gunstar Heroes, a game completely unlike Final Fantasy Legend III and not the subject of this article, was developed by Treasure, a developer that has gone down in computer game history as one of the most celebrated for run-and-gun platform shooters. Every game Treasure puts out is met with widespread praise – yes, even their McDonald’s commissioned fast-food platformer, McDonald’s Treasure Land Adventure – Masato Maegawa, the producer of Gunstar Heroes and the aforementioned Hamburglar game, is revered in the Sega fandom almost as much as Hironobu Sakaguchi in the Final Fantasy fandom.

As fans, we tend to gravitate toward the meteoric figures involved in a game’s development, typically the concept-people, “idea guys”: the directors and producers. We raise these individuals to celebrity status and treat them with 13th-century-BC-peasant-levels of Zeus idolatry. However, these “gods of gaming” had a whole team of people who brought their vision to life – the programmers, those who painstakingly keyed and clicked out the pixels, made the music play at the right time, and all around ensured the game wasn’t an unplayable mess. Despite this, in almost every medium, an “ideas guy” garners far more recognition than those who made their ideas possible to begin with. Hideo Kojima, Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, Shigeru Miyamoto, Will Wright, the list goes on. But why do we do this? Well the answer is simple: Final Fantasy Legend III.

It should be noted that, especially in Japanese game development, these “idea guys” often moved up the ladder by proving themselves; many went to university for something games-adjacent, and most programmed for other games before they became directors. Many directors and producers help with the nitty-gritty programming of their own game as well. Akitoshi Kawazu, creator of the SaGa series, is one such person. What I’m trying to convey is, these people are not without technical game-smithing talent; however, the point stands: we throw their names around far more than the traditional programmers involved with a game’s creation. I include this paragraph out of fear of being attacked online by someone who knows far more about their gaming-heroes than I do (please don’t hurt me).

*out of respect for the brave souls messing with the 1s and 0s; full endgame credits roll for Final Fantasy Legend III, played upon defeating the final boss

*out of respect for the brave souls messing with the 1s and 0s; full endgame credits roll for Final Fantasy Legend III, played upon defeating the final boss

Development of Final Fantasy Legend III was handled by an entirely different team at Square than the previous two titles, Square’s Osaka Department; a new development team that later went on to spearhead Final Fantasy Mystic Quest. Akitoshi Kawazu, the “ideas guy” behind the SaGa series, was preoccupied with the development of Romancing SaGa for the Super Famicom. Consequently, the responsibility for Final Fantasy Legend III fell into the hands of a new “ideas guys” named Kouzi Ide and Chihiro Fujioka, the latter primarily recognized as a composer for their work on Earthbound. While Fujioka also contributed to the game’s music, the primary composer was a newcomer named Ryuji Sasai. Among the previous SaGa team members, the only returning member was Katsutoshi Fujioka, concept artist who helped establish the series’ science-fantasy and occasional-cyberpunky aesthetic.

The resulting game is one that – while competent and complete – is not a SaGa game. The vision was lost somewhere in the handoff between Akitoshi Kawazu and the Osaka Department. Without Kawazu to guide the game’s direction, it spiraled out of control and morphed into something entirely non-SaGa-like; more akin to a Final Fantasy game than a SaGa game, something Kawazu was clearly trying to avoid from the beginning. One gets the impression that Kouzi Ide was given the SaGa handbook but didn’t bother to read it; at best, he might have skimmed a few pages.

William Gibson wrote in his novel Neuromancer, “Cliches became cliches for a reason; that they usually hold at least a modicum of truth, and the following cliche is truer than most: You can’t know where you’re going if you don’t know where you’ve been.” I had an art teacher in highschool tell me something similar. I was a rebellious kid and fancied myself an artist of sorts, also a writer and a musician; hell, I was in a “band” with the only other writer on this site (“band” in quotes because we were awful primarily because I wasn’t a musician). I considered myself an overall genius at everything; with the perfect excuse if I failed at anything: I just “wasn’t trying very hard” or “didn’t care”; but I could do it, and I could do it better than you if I actually applied myself, or so I believed.

Around that time, I was interested in the “dada” or “anti-art” movement; a concept that questions the true meaning of art, denies the accepted definitions of what constitutes art, and rebels against the perceived pretensions of modern art. In this way, “anti-art” is the most pretentious of all artistic philosophies, an irony lost on my high school self. Hindsight being perfect vision, the idea of taking a picture of a toilet and being praised for it was appealing to me, in a clearly narcissistic and lazy way. So, when the teacher assigned a project to paint a picture of a house in black and white as an exercise in shading, I painted the most gaudy and colorful house I could possibly paint. I turned in that assignment, thinking I was the coolest person on the planet.

*Marcel Duchamp Fountain, 1917; seminal work of “dada” art movement

*Marcel Duchamp Fountain, 1917; seminal work of “dada” art movement

Needless to say, the teacher failed me and told me something I didn’t care for at the time: “you can’t break the rules if you don’t know the rules to begin with.” Shortly after, I learned even the most famous “anti-art” artists knew how to draw a realistic person in perfect detail. They were artists and they knew what they were doing. They mastered the rules so they could break the rules. I, on the other hand, was skipping a step. I was a fraud.

All of this serves a purpose: the new creative team behind Final Fantasy Legend III broke the rules established by SaGa creator Akitoshi Kawazu, but they did so without fully understanding those rules. What we end up with is an ambitious title lacking the SaGa-soul, which is obviously crucial for a SaGa game. This is precisely why “idea guys” achieve celebrity status, particularly in the realm of Japanese computer games. Their ideas are so deeply ingrained and realized in their work that their absence is keenly felt. The best directors leave a piece of themselves in their work that is almost impossible to replicate without a true understanding of their vision.

II. Anyways, Let’s Talk About Chrono Trigger

Final Fantasy Legend III follows a group of adolescent adventurers led by a spiky-haired boy as they embark on a quest to prevent the destruction of their world by a Lovecraftian cosmic horror. On this quest, they discover a palace housing a jet-like craft that allows them to travel through time. Our heroes repair and use this vehicle to influence past and future events in an effort to subvert the destruction of their world, making friends and enemies along the way; and no, this is not a retelling of the plot of Chrono Trigger with the names swapped out. Final Fantasy Legend III predates Chrono Trigger by almost four years.

In Chrono Trigger, we control a red-haired teenager creatively named Crono; a silent protagonist who serves more as a player insert than a fleshed out character. In Final Fantasy Legend III you play as Arthur, a brunette boy from the future, sent back in time to save the world. Coincidentally, my son’s name is Arthur; actually, this is not so much a coincidence as it’s the only correct name to give the protagonist of any role-playing game – King Arthur did wield Excalibur after all – meaning most developers have really dropped the ball in this regard; for example, Tidus? Half of the world’s population can’t even pronounce the name Tidus properly. Arthur is a far better choice and any half decent writer knows this.

*cast of Chrono Trigger, drawn by Akira Toriyama; a much better cast of characters than those found in Final Fantasy Legend III

*cast of Chrono Trigger, drawn by Akira Toriyama; a much better cast of characters than those found in Final Fantasy Legend III

Tangent aside, Final Fantasy Legend III sets itself apart from previous SaGa games by introducing a fixed cast of characters, each possessing unique names, races, and other typical default attributes one may expect to find in a role-playing computer game. These characters include Arthur and Sharon, both of whom are humans. Sharon’s unrequited crush on Arthur is hinted at through a single line of dialogue at the outset of the game, but oddly never explored further, even in post-game credit scenes where you would expect something like this to be expanded on in older games (like a shot of Arthur and Sharon living together in a town or something). The last two characters are Curtis and Gloria, mutants who have almost no dialogue worth mentioning at any point in the game. As such, if Sharon, Curtis, and Gloria were replaced with player-created characters, there would be no impact on the plot whatsoever; ultimately, Arthur is the only necessary piece for the plot to play out in its intended fashion.

This change is where we begin to witness Osaka Department deviating from the established SaGa rules and basically losing the plot entirely. With the inclusion of predetermined characters, the sense of crafting your own unique party is gone, a fundamental element of the Game Boy SaGa games that has been lost in the ether. You are forced to live out the developer’s fantasy instead of your own. In this regard, Final Fantasy Legend III bears a stronger resemblance to a Final Fantasy title rather than a SaGa title. Moreover, considering the limited depth of each character’s personality and lack of important dialogue, it falls short of achieving even a hint of Final Fantasy’s character driven goodness.

*cast of Final Fantasy Legend III; Arthur, Curtis, Gloria, and Sharon, respectively; original concept art compared with Americanized NA manual art

*cast of Final Fantasy Legend III; Arthur, Curtis, Gloria, and Sharon, respectively; original concept art compared with Americanized NA manual art

In Chrono Trigger, you have Lavos, and in Final Fantasy Legend III, there’s Xagor – an evil being hailing from Pureland, a beautiful world inhabited by monsters. Instead of completely obliterating our hero’s world with his tremendous power, Xagor devises a brilliant plan: summon a colossal jar of water in the sky that unleashes an endless torrent, flooding the land. The inhabitants of the hero’s world aptly name this water-filled jar the Pureland Water Entity (a name that passes the on computer games “rule of cool” test for its stating-the-obvious-mysteriousness). This flooding process is very slow, spanning generations, as evidenced by our time-traveling escapades. Xagor’s flooding scheme is similar to a James Bond villain securing Bond to a chair, poised before a crossbow triggered by a taut string slowly burning under a flickering candle flame, affording our heroes ample time to devise a solution to the problem; in other words, it’s dumb, but also cool.

The solution to the problem is, of course, time travel. In Chrono Trigger, there was the time machine Epoch, and in Final Fantasy Legend III, there’s Talon. Both serve as main fixtures in the hero’s journey for both games, functioning as hubs of sorts and later as vehicles to travel the world. Utilizing the timeship Talon, our heroes embark on a journey through three distinct time periods in an effort to stop Xagor and the Pureland Water Entity. These three time periods serve as separate worlds, reminiscent of the worlds found in SaGa 1 and 2, although lacking the same level of creativity. They can be compared to the last Christmas gift your grandma gave you (likely socks), although my grandma once gifted me Quiet Riot’s album “Mental Health” on vinyl, which, admittedly, is cooler than most gifts but not an album I would ever admit listening to.

Unlike Chrono Trigger, which encompasses multiple time periods ranging from prehistoric to end of the world, Final Fantasy Legend III’s time periods range from last week to Mom’s next birthday. The characters encountered throughout each time period remain the same, albeit at different stages of their lives, and the world’s scenery undergoes minimal changes between time jumps, except for the gradual increase in water levels caused by the Pureland Water Entity, this is especially apparent in the future where the world is more waterful than Pokemon Ruby and Sapphire (“waterful” being the third word I’ve made up for this article so far, a practice I plan to continue as long as it sounds good).

*Pureland Water Entity and world map of Final Fantasy Legend III, per the Game Boy manual; see the Pureland Water Entity in the far right

*Pureland Water Entity and world map of Final Fantasy Legend III, per the Game Boy manual; see the Pureland Water Entity in the far right

This lack of worlds, specifically lack of unique worlds, illustrates another miss by Kouzi Ide and his team; simply adding time travel to your game doesn’t make up for a lack of creative world-building. In SaGa 1, you traveled through a post-apocalyptic world while being chased by a giant flame bird. In SaGa 2, you went to Edo era Japan, stopped a literal banana racket, then fought a demonic shogun on a roof with a crescent moon backdrop. In SaGa 3, you go to your world in the future and there’s a bit more water and your grandma dies of old age.

The primary objective of most time travel in the game is to acquire new units for your timeship, Talon. These units grant Talon various powers and weapons. For instance, there is a unit that enables travel to the future and another that allows travel to the past. As such, these units serve a similar plot progressing function as magi in SaGa 2. Consequently, the progression unfolds as follows: begin in the present time (although the notion of a fixed “present” is dumb and arbitrary, considering any moment experienced is inherently the present, ok, taking off my redditor hat now), locate the unit for “future” to enable travel to the future, find the unit for “past” within the future to facilitate travel to the past, and ultimately, discover the unit for “Pureland,” enabling our heroes to journey directly to Pureland and confront Xagor head-on. The sequence of these events may be incorrect as the time periods in Final Fantasy Legend III end up feeling samey and boring; idea being cooler than execution, much like a highschool crush. In fact, you jump back and forth so much early on in the game that it almost feels like you’re not time traveling at all.

Oh yeah, you also go to a floating island and the underworld at one point, both highlights in an otherwise bland adventure.

Towards the endgame, it is revealed that our timeship, Talon, is actually built around a human brain. The impression conveyed is that the timeship consists of a blend of metal, wibbly-wobbly-timey-wimey stuff, and a human brain integrated into the hardware, as suggested by in-game text. This revelation raises intriguing implications. Just imagine, trapped within a hunk of metal, manipulated by kids who use you as a tool for their heroic play, silently witnessing the weird-kid-things kids do when they believe no one is watching – enough to drive anyone insane. If I were tasked with creating the sequel to this game, it would revolve around Talon subjecting these kids to brutal torture, locking them inside its metal body and forcing them to kill each other, only to rewind time and make them do it again. The title of this sequel would be “Final Fantasy Legend IV: I Have No Fun and I Must Scream.”

As I typed the previous paragraph, I found myself nervously pondering my own mental state, considering I have two kids of my own – let’s just attribute it to edginess and move on.

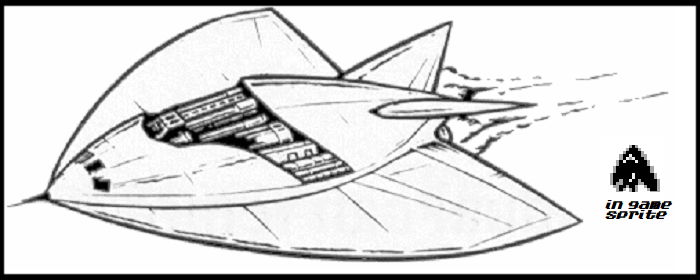

In actuality, Talon is the coolest character in the game. As previously mentioned, it is revealed that Talon was created using a human brain. Throughout the game, Talon unexpectedly takes independent action at crucial moments to assist Arthur. Incorporating this concept into the gameplay, once you acquire a specific unit and install it in Talon, you gain the ability to fly Talon across any world map and when encountering random foes while riding Talon, it immediately initiates its weapon systems and attacks the enemy before your first turn, often eliminating the enemy outright without any input from the player.

In the final dungeon, Talon emerges out of nowhere and blasts a hole in an obstacle, enabling your progress; and in one of the most remarkable instances of Game Boy storytelling I’ve ever experienced, during the final boss battle, when all hope seems lost, you hear a loud Game Boy soundchip buzz – it’s Talon, swooping in, firing its cannons at the boss. Talon continues its assault on the boss for the rest of the battle.

*concept art of Talon found in Final Fantasy Legend III’s Game Boy manual; alongside Talon’s in-game sprite

*concept art of Talon found in Final Fantasy Legend III’s Game Boy manual; alongside Talon’s in-game sprite

The player gets the impression that Talon is its own character, capable of independent thought and deeply invested in aiding the heroes in achieving their objectives; and the player is right, as it turns out that Talon is Arthur’s father, who embarked on a quest to defeat Xagor but was ultimately defeated. His body was salvaged, and his brain was transplanted into Talon – Arthur’s father was with him the whole time.

Before the credits roll, you revive Arthur’s father using science (or magic), and he asks for the name of the hero who saved him, to which Arthur provides. Arthur’s father then states, “That’s a good name. I think I’ll name my son after you.”

But hold on, because this is where things get complicated.

III. Time Travel and Causality Loops

If I were the writer of Final Fantasy Legend III, the aforementioned plot summary would only be Chapter 1. The rest of the story would involve correcting the universe-shattering causality paradoxes caused by what just happened.

Let’s start from the beginning. Two young men named Jupiah and Borgin travel to Pureland to confront Xagor. They are defeated, and Borgin manages to escape. Jupiah’s body is salvaged, and his brain is transplanted into a time machine called Talon. Using Talon, Borgin sends Jupiah’s son, Arthur, back to a time period before his birth in order to prevent the destruction of the world. Arthur, after a series of heroic adventures, eventually triumphs over Xagor in Pureland. As a final act of heroism, Arthur restores Jupiah to human form thereby allowing Jupiah to live out the remainder of his life in peace. Jupiah, feeling grateful to the hero who saved him, decides to name his future son after this hero. Presumably, at some point after these events, Jupiah meets a woman, and they have a child named Arthur.

All of this checks out until we introduce the fact that Arthur is Jupiah’s son. This is where things start to become complicated.

It is assumed that Arthur was born during a time of peace before (or maybe after?) the appearance of the Pureland Water Entity, which initiated the flooding of the world. When the Pureland Water Entity emerges, Jupiah is motivated to defeat Xagor to stop the flooding, but unfortunately, he fails. However, Jupiah’s son arrives from the future and rescues him. Jupiah then proceeds to meet a woman and eventually they have a child. Jupiah names this child Arthur, in honor of the hero who saved him – unbeknownst to him, this hero is actually his own son from the future, Arthur.

*the paradox begins

*the paradox begins

This raises two primary questions. The first question is, where did the name Arthur come from? It is illogical for someone to be the cause of their own birth or naming. To put it simply, it would be akin to me traveling back in time before my own birth and instructing my father to name me Forrest. By doing so, I would essentially be naming myself. However, if I had not already been named Forrest without my own intervention, how could I possibly go back in time and suggest that particular name?

In essence, this represents a form of causality loop known as the bootstrap paradox, also referred to as a predestination paradox. It entails a temporal loop in time travel where one event triggers a second event, which was in fact the cause of the first event. This creates an illogical and unsolvable loop, a paradox. In the case of Final Fantasy Legend III, Arthur’s birth serves as the first event, while Arthur saving his father’s life serves as the second event. The second event causes the first event which causes the second event which causes the first event which causes the second event, etc.

This concept is later explored in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time through the “Song of Storms” quest. Link, who is capable of time travel, learns the song from the windmill man at Kakariko Village in the future. The man mentions that he learned it from a child in the past. Utilizing this knowledge, Link travels back in time and plays the song for the windmill man, thereby teaching him the song — so, where did the song originally come from? While I doubt Zelda was inspired by Final Fantasy Legend III, it is an interesting bit of trivia that the latter did bootstrap paradoxes before Zelda made it cool.

*bootstrap paradox illustration created by yours truly

*bootstrap paradox illustration created by yours truly

I did mention two questions, and we have addressed the first. The second question is: If Arthur successfully defeated Xagor and prevented the emergence of the Pureland Water Entity, which event initiates the events of the game? It cannot be Xagor, as he has already been defeated by Arthur in the past. In this predicament, one might assume that once Xagor is vanquished time for those in the future rewinds to a point where Xagor never manifested. However, if time were to reverse, the defeat of Xagor would never occur, resulting in Xagor’s reappearance, leading to another loop! This type of loop is known as a “grandfather paradox”, which we will loop back to in a paragraph or two.

There are two main schools of thought around time travel and its consequences. The first school of thought is that time travel to the past would be extremely dangerous, to the point where you could prevent your own birth or even drastically alter the course of human history if you interfered in any way. This is encapsulated in the concept of the butterfly effect, which is supposedly illustrated in the movie titled “The Butterfly Effect” (a movie I’ve never seen). It suggests that even a small, insignificant change in the past could cause a ripple effect that drastically alters the future.

For example, let’s say you go back in time and accidentally kick a small pebble onto a sidewalk. An hour later, a roller skater skates down the same sidewalk and hits the pebble, tripping. This roller skater then tumbles into the road and hits a moving car, causing a fifty-car pile-up resulting in the death of a woman who would have become the president of the United States in 2032. That president would have gone on to prevent World War III. So, when you return to your own time of 2099 (or whatever), the world is ravaged by nuclear holocaust.

The second school of thought suggests that any interference with the past would result in a multiversal effect, causing the timeline to branch off into a new timeline.

Let’s consider the “grandfather paradox” mentioned earlier: if you were to travel to the past and kill your own grandfather, you would effectively erase your own existence, as the circumstances leading to your birth would no longer unfold. However, this implies that you were never born in the first place to carry out the act of killing your grandfather, ensuring his survival, which in turn ensures your birth, enabling you to travel to the past and kill your grandfather. Obviously, this presents a significant problem because it makes no sense, which is why it’s a paradox.

However, in the second school of thought, killing your grandfather would result in the emergence of a new timeline (or “universe”, a term I’ll use interchangeably) that is separate from the timeline you originated from; thereby, no paradox would occur. And while this theory provides a less paradoxical explanation for meddling with the past, one gets the feeling it was created solely to solve the multiverse of issues that time travel to the past presents. This theory also implies the existence of an infinite number of universes as every choice would branch off into a new timeline, which poses significant narrative problems, especially in superhero fiction where “multiverses” are as abundant as, well, a multiverse; for a superhero to truly maintain their superhero status, they would have to save each doomed universe, a potentially endless task.

*crude illustration of the split timeline theory, preventing grandfather paradoxes

*crude illustration of the split timeline theory, preventing grandfather paradoxes

This is partially why I find the idea of a “multiverse” in literature dumb and incoherent, especially in comic book narratives, particularly when the heroes are deeply committed to saving lives. After all, if there are infinite universes, there are infinite people in need of saving – the ultimate humanitarian crisis. Can a hero truly be considered a hero if they only care about the people in their own universe? Sure, one could argue that there is an alternative version of Superman in each universe, thereby circumventing the need for Superman Prime to go around saving every universe. However, this is not guaranteed, and Superman is not invincible; he has likely died in several timelines.

There exists a third, less-discussed school of thought, which happens to be my personal favorite. In the Doctor Who episode “Waters of Mars,” our titular hero, the Doctor, succumbs to an arrogant impulse and decides to save someone who was destined to die, as their death played a crucial role in the future advancement of humanity. However, the Doctor, being the last Time Lord and believing he has dominion over time itself, goes ahead and saves this individual. To the Doctor’s surprise, this person ends up committing suicide, thus allowing history to unfold as intended – only the “little details” were changed.

This particular school of thought revolves around the notion that time, like a sentient entity, corrects itself to ensure that history (or the future, depending on your perspective) remains unaltered. It’s a cool concept, albeit one that raises certain philosophical dilemmas such as the idea of predetermination and fate.

To finish off this section: this is why time travel, particularly time travel to the past, exists only in fiction. If it did exist in our reality, we would be meeting our unborn future family members far more often than we do now (never), and we would most likely already be caught in a temporal causality loop, similar to the movie “Groundhog Day” or that one episode of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” where Willow casts a time loop spell (or something).

Consider me a disbeliever – although, we could already be caught in a causality loop and not even know it.

IV. Gameplay or: The Save File Test

While we’re discussing loops, consider this: You’re holding the forward direction on the d-pad as you walk through a door. The door transports you to a new area with a reversed perspective from the one you just exited. Despite intending to conserve your forward momentum by continuing to hold forward, the perspective change flips your direction, and you inadvertently walk right back into the door you just exited. If you continued to hold the forward direction, due to the reverse perspectives, you would go through the initial door again then immediately walk back through the door you just exited from – again! An endless loop!

If this hasn’t happened to you before, it’s probably because you haven’t played many 3D computer games, where this type of situation is common due to poorly conceived camera cuts. It’s far rarer in 2D games, where clever door-tile placement prevents the issue entirely. However, in the case of Final Fantasy Legend III, it happens all the time, especially in hub zones like the timeship Talon – an area where you would expect the developers to catch this detail and correct it, considering how often you have to go through this zone.

*an example of an endless “one direction” door loop; still more interesting than Harry Styles; developers, don’t do this.

*an example of an endless “one direction” door loop; still more interesting than Harry Styles; developers, don’t do this.

The first chapter of this article is called “Prelude to Pedantry” for a reason. Expanding on this pedantry, imagine for a moment that you’re playing Contra for the Nintendo Entertainment System. To fire your gun, you have to rapidly tap the A button. This quickly puts a strain on your finger, so you decide to invest in a third-party controller with a turbo switch – a switch that changes the behavior of holding a button down to “on and off and on again, etc.” from “the button is being held down.” This effectively allows you to hold the A button and continuously fire your gun – a helpful thing for run-and-gun shooters. However, it’s not necessary for Gunstar Heroes because it has native turbo, like any good run-and-gun game should (this is Treasure we’re talking about, after all).

Now, imagine that, like Gunstar Heroes, a role-playing computer game has this feature programmed into it natively. Perhaps the thought process behind this decision was, “this will help players rush through battle text!” or “this will make it faster to input previous selections again!” Whatever the reason, the result is that when navigating any menu, holding the confirmation button for longer than a millisecond selects whatever option the cursor happens to be on, taking you to the next menu option. Now, imagine you unintentionally hold the button for three milliseconds – suddenly, you’ve accidentally selected a bunch of menu options!

Let’s suppose you’re trying to input character actions in battle, and you mistakenly hold down the confirmation button for a millisecond longer than you should. Now, instead of selecting “cure,” you’ve selected “flare,” and as a result, you’re dead.

I bring this up because this is how Final Fantasy Legend III behaves – constantly accidentally selecting options you don’t intend to, as the turbo function is permanently applied to all confirmation button presses. But it would be unfair for me to deduct points from Final Fantasy Legend III alone, as this is an issue present in all the Game Boy SaGa games. Besides, I don’t give out points to begin with; nevertheless, this turbo issue seems to occur more frequently in this game compared to the others, so I thought I would mention it. In truth, I wanted to bring it up in my SaGa 1 and 2 articles, but it slipped my mind.

The game design follies mentioned above are not game-breaking by any means; rather, they are minor quirky annoyances. In fact, Final Fantasy Legend III does not have any “game-breaking” issues. The true problems that exist are more conceptual than technical, and there are several of these conceptual issues that we will delve into. However, before we explore those issues, let’s focus on the positives.

The first positive, and something I didn’t realize I needed until I experienced it firsthand, is the addition of jumping. A minor annoyance I encountered while playing the first two SaGa games was the occasional, but not infrequent enough, occurrence of NPCs blocking pathways and entrances. In the past, when this happened, I would try to push past the NPC, hoping they would move. However, in Final Fantasy Legend III, you can simply jump over any NPC! It may sound insignificant, but it’s actually one of the best improvements over the previous two SaGa games.

Another advantage of this jump mechanic is that, although the dungeons themselves may not be the most interesting to look at, there are plenty of dungeon jumping puzzles that require you to leap over holes or obstacles on the floor to progress. This adds a twist to dungeon exploration that is not commonly found in other 90s role-playing computer games, especially those of the 2D variety, and especially the previous SaGa games which featured highly linear exploration, albeit through significantly more eye-popping dungeons.

*a dungeon jumping puzzle that took me far too long to figure out

*a dungeon jumping puzzle that took me far too long to figure out

And you’ll find yourself jumping around a lot due to all the stuff in Final Fantasy Legend III – the content, there’s a lot of it. If you were able to clear SaGa 1 in three hours and SaGa 2 in six hours, SaGa 3 will likely take about ten hours to clear, maybe a bit less. Final Fantasy Legend III offers far more content than its predecessors, including several optional quests – something that was completely absent from previous entries in the series, not including SaGa 2’s sole optional dungeon.

Aside from traveling through time to collect remnants of magical swords and shields; one particular optional quest has you gather a magic seed in the future, travel back in time to plant the seed, and then return to the future to interact with the magical tree that grew as a result of your time meddling; similar to the situation with the Deku Tree or magic beans in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, just done seven years earlier – the similarities are getting suspicious now.

Final Fantasy Legend III’s new development team deserves praise for creating a competent turn-based combat system that surpasses both previous SaGa entries in terms of engagement and complexity; placing greater emphasis on immunities and exploiting elemental weaknesses in battle, it takes the strategic elements introduced in SaGa 2 and levels them up, maybe by one or two levels, not actually by much. Unlike the previous entry, which lacked meaningful exploitation of weaknesses (or perhaps I overlooked it, if so that’s simply evidence that it wasn’t necessary), such tactics are now required to achieve victory, sometimes – better than never.

Final Fantasy Legend III also includes numerous buff spells that were not present in older games, adding a new tool to utilize in battle. Additionally, “ancient magic” was added, which requires items to create and results in extremely (over)powerful spells like Nuke and Flare.

*a battle scene; return to sea monke

*a battle scene; return to sea monke

In contrast to the first SaGa, where one could rely on mindlessly pressing the confirmation button to win every battle, like a trust fund baby mindlessly relies on their inheritance to subvert every life struggle, the aforementioned weakness and immunity changes require players to actively focus on battles. Otherwise, prepare to become very familiar with the returning “Would you like to start this battle over from the beginning?” death prompt introduced in SaGa 2. However, this mechanic had a lore reason in SaGa 2 that is missing in Final Fantasy Legend III, implying our characters can just resurrect themselves and rewind time whenever they want – more pedantry.

It’s important to note that combat in Final Fantasy Legend III is not groundbreaking or very complex compared to other turn-based games from the same era, such as Dragon Quest IV or Final Fantasy IV, which incorporated more advanced battle gimmicks to shake things up. For example, Final Fantasy IV featured bosses like Mist Dragon, who could decimate your party if attacked at the wrong time. Nothing like this exists in Final Fantasy Legend III, although it comes close to achieving similar effects at times, primarily through its reliance on immunities that force you to change strategies when dealing with certain enemies. This becomes especially apparent when facing bosses, as they now pose a greater threat than random encounters.

*Ashura, a recurring boss, with two Lizalfos from the Zelda series

*Ashura, a recurring boss, with two Lizalfos from the Zelda series

Bosses in Final Fantasy Legend III have increased health and deal more damage per turn compared to previous games in the series. Although many bosses can still be defeated by spamming attack magic with two characters and group heals with the other two, the game manages to subvert this strategy often enough that it doesn’t feel like complete child’s play. Another interesting bit of trivia is that Ashura returns, being a staple boss in the previous two SaGa games. Like Gilgamesh of the Final Fantasy series, Ashura appears in every game without explanation, considering they’re all separate universes. Perhaps, opposite of Superman Prime, Ashura travels the multiverse destroying every universe instead of saving them.

Balance changes also extend to random encounters, as the game no longer throws dozens of monsters at players all at once. Instead, all monsters are now displayed on the screen, unlike in SaGa 1 and 2, where the monster sprites only represented the type of monster you were fighting, not the number of them. As a result, there are significantly fewer monsters to contend with in each battle, although these monsters are usually more dangerous to compensate. It feels more manageable overall. This makes Final Fantasy Legend III feel less “cheap” than its predecessors, where being overwhelmed was a frequent occurrence that could easily lead to throwing the controller or pouring lighter fluid on the console and setting it on fire, something I haven’t done (yet).

The monster sprites themselves, although frequently reused, have undergone either a significant upgrade or a notable downgrade. It’s hard to tell, as the sprites range from extremely high quality to comically low quality, sometimes showcasing a “so bad it’s good” aesthetic. As a result, the monster sprites are always interesting and unquestionably the best in the Game Boy SaGa series; at least in this writer’s entirely subjective opinion.

*small collection of some of my favorite monster sprites: cat mummy, ronin, low-quality merman, Ghouls and Ghosts demon, and brain-in-a-vat-bro

*small collection of some of my favorite monster sprites: cat mummy, ronin, low-quality merman, Ghouls and Ghosts demon, and brain-in-a-vat-bro

Final Fantasy Legend III’s inventory and weapon systems have undergone a significant overhaul. In past games, each character had their own inventory with limited item slots. This has been entirely removed in favor of a free-for-all system, where any character can access a shared inventory during battle that is separate from their own equipment. The drawback is that characters can no longer carry multiple weapons simultaneously, so there is no more waving a chainsaw around while propping a nuclear rocket launcher over your shoulder, like in the SaGa 1 concept art. In fairness, the SaGa 3 concept art shows our heroes holding only one weapon at a time, so you can tell Katsutoshi Fujioka was on point in regards to knowing the gameplay systems at work within the games he was drawing for.

Circumventing the drawback of weapon restrictions, our heroes can now swap weapons mid-battle without losing a turn. Additionally, weapons no longer have durability, making them immune to breaking. One minor issue is that the new user interface for character equipment is dumb, as it doesn’t clearly indicate which line corresponds to which type of equipment. Regardless, these changes contribute to an inventory system that requires far less micromanagement compared to previous SaGa games, where battling with limited inventory space was as common as random encounters.

*dumb equipment UI: someone please explain what “Bronze” is referring to

*dumb equipment UI: someone please explain what “Bronze” is referring to

The combat presentation underwent a complete overhaul, drawing inspiration from Sega’s role-playing series, Phantasy Star, by showing the back sprite of each character during battle. This change adds an aesthetic flair to the battles while also serving the practical purpose of visualizing the combat in a more intuitive way. Since the text-based combat log from previous titles has been significantly toned down, this change was necessary to fully convey what was happening in combat. Now, our characters exhibit movement when they attack, and damage numbers and status effects are visually represented on the screen rather than in the combat log.

Somewhat unrelated but some say Star Trek predicted the cellphone, citing the frequently used communicator as proof of this. Well, Final Fantasy Legend III didn’t predict anything, however, it was one of the first games to include an auto-battle function, following in the footsteps of Dragon Quest IV, which was released one year prior. Auto-battle functions as a toggle you can switch on for any character except Arthur; once switched on, the characters will proceed to use every buff and healing spell they have, often resulting in a slow and very stupid death. This auto-battle feature, while innovative for its time, is a completely useless addition, only serving as a precursor to the automatic nature of mindless gacha role-playing mobile “games” that I will instead be calling lottery software from now on. Auto-battle is a feature to avoid, but a feature nonetheless; akin to WiFi on a microwave – nobody asked, and nobody cares.

*Dumb equipment UI: Someone please explain what “Bronze” is referring to

*Dumb equipment UI: Someone please explain what “Bronze” is referring to

It’s unfortunate that these improvements weren’t added in SaGa 2, as they are now confined to a game that fails to grasp the essence of what makes SaGa so special. In a departure from previous SaGa games, and another example of the Osaka department losing the plot, Final Fantasy Legend III abandons the established “activity-based” skill progression system in favor of a traditional leveling system. As such, each character starts at level 1 and progresses through the game in cookie cutter role-playing fashion, their stats increasing in a predetermined manner.

With this change, the concept of specializing your characters through focused training is gone. Characters are only proficient in what the developers want them to be proficient in, leaving practically no room for meaningful character customization. As a result, one would expect every endgame save file to have the same party with the same equipment and spells, with only the character names being different. However, even the latter is unlikely as every character has a default name.

Compounding this lack of customization, the baffling decision to remove a player-created party in favor of a bland group of predetermined teenagers has a number of downstream effects on the gameplay. For one, you don’t pick the race of your characters anymore; this is predetermined by the developers: two of the characters are human, and two of them are mutants – another point of customization lost.

Mutants lost their ability to learn spells naturally and, as a result, lost everything that made them unique. Since both races now learn magic from magic shops, the need for mutants to learn magic innately has been eliminated. This also ensures that both mutants in your party will have the same optimized spell selection by the endgame.

Mutants now only differ from humans in that their magical stats are higher, making them more akin to standard fantasy wizards instead of the unique SaGa staples they once were. However, one thing remains true: mutants are still overpowered, a SaGa staple thus far. This is because magic is still incredibly useful for blasting multiple enemies at once, and since mutants excel at magic, they are the ones most suited to do the blasting.

*Gloria, the mutant, casts Quake on a group of monsters, decimating them all; also meat

*Gloria, the mutant, casts Quake on a group of monsters, decimating them all; also meat

The robot and monster races still exist in some capacity technically, albeit in a very strange, backwards way. Robot parts can now be grafted onto a character, transfiguring them into a robot, or a character can eat monster meat to become a monster. Both of these actions are accessed through a menu prompt after battle. And in a case study on why you shouldn’t default prompts to “yes,” it is entirely too easy to accidentally body-mod your characters if you’re holding the confirmation button a little too long at the end of a battle; early in the game I accidentally turned Arthur into a weird robot and couldn’t figure out how to change him back until an hour later when I got the “toilet unit” for Talon. Yes, the toilet reverts transfiguration, don’t ask me why or how.

Ignoring the fact that grafting robot parts onto a person is a little weird and horrific, this mechanic ends up being unnecessary; something you can just do if you feel like it for fun (or something). I didn’t find any benefits in transforming any character into a robot or monster. In fact, they always ended up being worse than their original state whenever I experimented with these body horror transformations. It seems like the creators added these transfiguration mechanics simply to claim that robots and monsters were still part of the game.

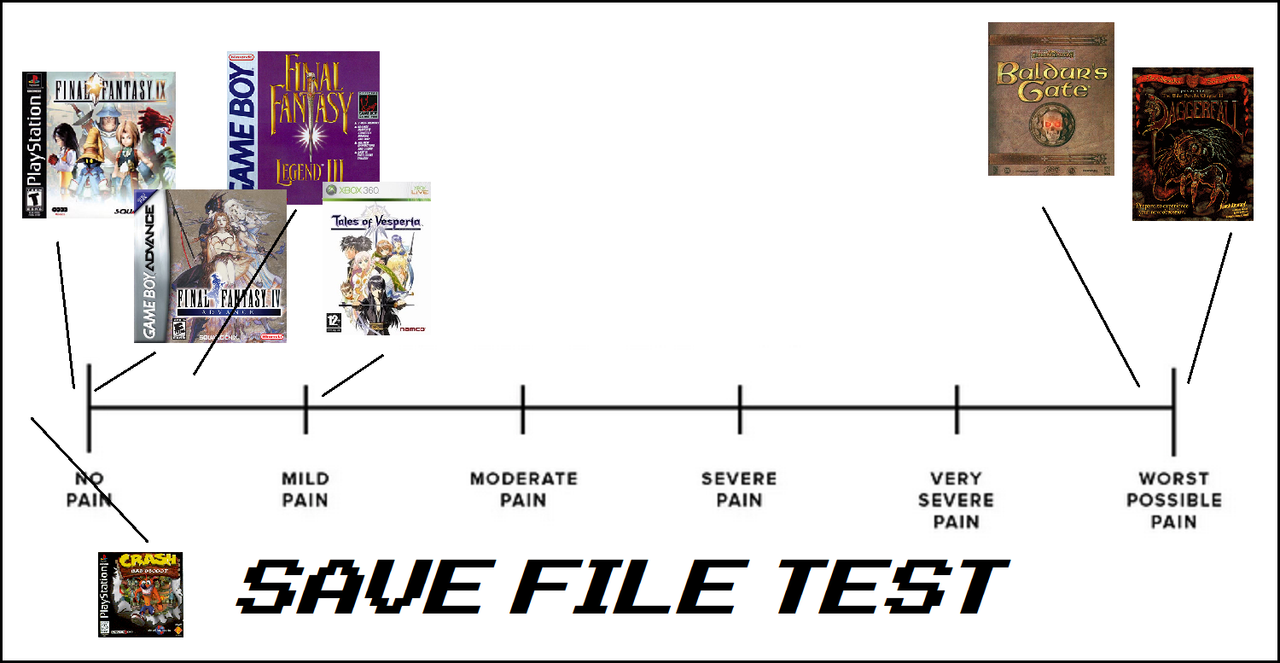

Final Fantasy Legend III does not score very high on the “Save File Test,” a term I just made up. This test assesses the level of variety found in a role-playing computer game, specifically concerning character building. Essentially, it examines the extent to which completed save files from different players would resemble one another. For instance, a game that offers extensive character customization, including features like race selection, stat distribution, a robust class system (especially those that allow multi-classing), unique equipment that goes beyond simply choosing the one with the highest attack stat, and (surely) some other stuff, would score very high and serves as the primary criteria for evaluation. Basically, if you load up a 100% Crash Bandicoot save, you know what you’re expecting – this should never be the case with a role-playing game (that I like).

As a measure of this test’s reliability, consider The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall the highest scoring game while something like Final Fantasy IX is the lowest, as the latter, if min-maxed, would have every character identical across every save file; Zidane would always have Ultima Weapon and all learnable skills, Steiner would have Excalibur II and all his skills, Vivi would have Mace of Zeus and all spells; you get the picture. On the opposite end of the spectrum, a Daggerfall save would be different between every player in significant ways; one save file may have a traditional orc warrior main character, another may have a dunmer mage who moonlights as an assassin, and another may have a personality-based imperial who tries their best to avoid conflict by smooth talking all the npcs; basically, it has variety – maybe too much.

*the save file test graph, simplified; ignore the “pain” bits (typo, seriously)

*the save file test graph, simplified; ignore the “pain” bits (typo, seriously)

Final Fantasy Legend III would score a 2 or 3 on the Save File Test, narrowly missing the lowest score due to the inclusion of monster and robot transfiguration mechanics; these mechanics, although unnecessary, provide a level of depth that games like Final Fantasy IX or IV do not have, offering some semblance of choice beyond the RPG basics. Alternatively, SaGa 2 would score a 6 (or something, this isn’t an exact science or a science at all) since it allows full character creation for each party member, including race selection, and enables you to train your characters according to your preferences, all of which are missing in Final Fantasy Legend III.

Of course, this does not tell us if a game is “good” or “fun,” both of which are dumb terms based around subjective experience. One could argue that a game boasting the most intricate character customization ever created, but can be completed within three minutes after character creation, would be deemed a “bad” game. I would likely agree with that sentiment, highlighting that character customization alone does not solely determine a game’s worth. However, it is important to note that the Save File Test does not aim to evaluate a game’s overall worth; its purpose lies in serving a specific niche by assessing the level of customization and depth in a role-playing computer game – that’s all.

Why is character customization so important anyways? Well, like most things in life, it’s not. But it’s important to me.

I enjoy creating things, which is one of the reasons I write these articles. The other reason is that I want to catalog the games I play since they take up a large portion of my time, and not documenting them in some type of “permanent record” feels like losing the experience to history.

Anyways, I like creating things. A game that provides me with tools to create stuff is always more appealing to me than one that lacks such tools; primarily why I find role-playing computer games so appealing, which have historically been known for character creation and branching stories ever since their tabletop ancestors established this trend back in 1974 with the original Dungeons & Dragons. However, an excessive amount of creativity can be overwhelming, so a balance is necessary.

Games like Daggerfall, I would say, score a 10 on the Save File Test. They offer an abundance of choices and freedom, which can be overwhelming. On the other hand, a game like Final Fantasy XI, an MMO with races and multi-classing, sits at about an 8 on the scale, which is a fair balance. Some people prioritize story, while others value presentation above all else. Personally, I appreciate a combination of all these elements, but player choice is what I value above all else.

A game where the predetermined hero saves the day in a predetermined way with the predetermined hero sword and predetermined hero spells does not appeal to me, both in terms of gameplay and narrative – this is precisely why I find Final Fantasy Legend III so offensive.

V. Conclusion or: Let’s Stop Talking About Chrono Trigger Now

As a foreword, I hate writing conclusions. I hate reiterating things I’ve already written just in a slightly different way; conclusions are the hardest part of an article for me to write, but I feel like this article needs a conclusion, so here we go; let’s stop talking about Chrono Trigger.

The developers of Final Fantasy Legend III were either time travelers or trailblazers, maybe both; incorporating ideas that were ahead of their time, such as a loopy time travel plot later recycled and greatly improved on by Square in Chrono Trigger, temporal hijinks that later became core Zelda gameplay mechanics, auto-battling that became a staple in role-playing games by 2023, and even a mechanic resembling HMs (hidden machines) later used in Pokemon (which came out 5 years after Final Fantasy Legend III); the latter of which I failed to mention in the main body of the article because there was just too much going on, but, yes, you can teach your characters to fly or swim with specific spells, although this is only used in the early stages of the game; quickly abandoned, like most ideas in Final Fantasy Legend III.

And that’s the problem. Final Fantasy Legend III, ambitious and grand in its scope, ultimately falls short in its half-baked amateurish execution, sometimes feeling like something I would write if I were tasked with coming up with a role-playing computer game about time-travel – obviously not a compliment; I bring stuff up, never circle back to it, abandon it, act like it never existed. I believe there was something I mentioned earlier in this article that I never circled back to, or maybe I didn’t. Anyways, the point is: wait, what’s the point?

Oh, right. Final Fantasy Legend III, good or not? Well, the narrative often jumps from one time period to another with no sense of gravity or cohesion, leaving the impression that several opportunities to utilize the time travel concepts were missed. Plot threads simply vanish, bizarre transitions occur out of nowhere to progress the story, character deaths are quickly circumvented with magical devices, and glaring plot holes masquerade as deep science fiction time travel paradoxes, sometimes feeling as if the developers accidentally stumbled upon paradoxical gold instead of intentionally including it. All these random tropes are piled into one crazy and ultimately confusing narrative, so carelessly constructed that not even Columbo could crack it.

*Columbo trying to understand the hidden logic of Final Fantasy Legend III

*Columbo trying to understand the hidden logic of Final Fantasy Legend III

And while the majority of the game feels like aimlessly doing stuff just to be doing stuff, none of that is important because Final Fantasy Legend III made me write over a thousand words on temporal paradoxes, which I would consider a significant achievement.

In terms of gameplay, the act of cutting through monsters with a laser sword continues to be just as gratifying as before, requiring strategic focus in combat rather than mindless button pressing. However, the combat experience could have been improved if we weren’t forced to control four heroes deemed so important to the plot that they had to be included by the development team. This odd choice diminishes the sense of achievement that comes from successfully utilizing a distinctive ensemble of player-created characters in the game’s hostile environment.

The implementation of an experience-based leveling system, as opposed to the skill-based progression system seen in previous SaGa titles, removes any significant character customization. This change has the potential to make every save file and replay identical unless players make use of the monster and robot transfiguration mechanics, which is more akin to picking between cat urine and orange juice than an actual choice. The overall experience quickly becomes bland for those who value a certain level of customization in their role-playing computer games.

*we did it! wait, what were we doing again?

*we did it! wait, what were we doing again?

Contrary to my sometimes overwhelming negativity, Final Fantasy Legend III is not a bad game. In fact, it stands out as one of the more comprehensive role-playing games available for the Game Boy. With its strategic turn-based combat, abundant levels of bite-sized content, and an overall sense of time-travel grandeur, it successfully encompasses many essential elements that make a computer game “fun”, whatever that means. However, it does lack a key role-playing game component, that of player choice. Essentially, if it didn’t fall short in this one aspect, which could be argued as the most important aspect for a SaGa game, it would be the perfect Game Boy SaGa game.

The new development team’s failure to grasp the essence of SaGa is evident, as they completely missed the point. SaGa has never been about controlling predetermined characters and leading them along a linear path of progression. The series’ original vision drew inspiration from games like Dungeons & Dragons and Wizardry, prioritizing non-linearity, especially in character development — this crucial aspect is absent in Final Fantasy Legend III, underscoring the significance of the original director, Akitoshi Kawazu, to the series. The absence of his influence is keenly felt in every facet of gameplay.

Much like my highschool shading project, Osaka Department turned in a game that, while technically competent, missed the mark because they didn’t understand the rules they were trying to break to begin with.

Final Fantasy Legend III is not a bad game. It’s just not a SaGa game, and I wanted to play a SaGa game.

As always, stop playing if you’re bored. Put the controller down. Go outside. Do something else. If you’re not having fun, it’s not worth it.

(Originally published on 5/27/2023)