Fishing for God

I: The Boy and the Brown Bear

Five o’clock, morning dew, and the fireball rises like a wizard’s cantrip ricocheting off the wild wind. Fully clothed in rip-worn blues and whites earth-stained from angling adventures of days gone by, I fish my tackle box of seen-better-days from behind the sliding screen that is my makeshift closet. Tiptoeing through the house so as not to wake Big Sis from her sickly sleeps, I head straight to the cupboard to collect my lunchbox generously filled to the brim with Mom’s perfectly wrapped rice balls. I sneak a quick bite off the largest ball; it’s luscious, as usual, and crumbles out of control when placed back into the metal box for future snacking.

I tiptoe silently towards the front door, where my trusty companion awaits: the child-sized fishing rod propped against the thin wooden wall of the flimsy shack we lovingly call home. The tatami mat below creaks loudly, but it wasn’t me this time; it was Mom: “Up early again to catch the Guardian Fish?” I nod vehemently, grab my pole with Sisyphusian determination, bear hug Mom, and close the front door behind me as I exit into God’s great and bountiful gift: nature.

I’m going to catch that Guardian Fish and rip its guts out.

When Mom told me Big Sis was sick and could only be cured by eating the innards of the Guardian Fish, it all clicked for me. This is my calling. I love to fish; to sit on the side of my chosen stream, cast my line, and contemplate the nature all around me as I wait for a bite; crickets chirping, fish splooshing once calm waters, bees bumbling buzzed-up flowers, limbs creak-cracking as squirrels play their tree games – the ecosystem: God’s great and bountiful gift.

And how do I fit into it all? God’s gift cares for me, provides for me, as long as I do my part; I catch the fish, I eat the fish – bones and all. The fish, with their hearty charred flesh and soup-flavoring bonemeal, sustains me and my entire village; no different than how the fish is sustained by smaller fish and the lion is sustained on the elk’s bloody, mangled carcass. I am not above it, merely momentarily on top.

I am the ecosystem.

So when Mom told me that Big Sis was sick and that I needed to catch the Guardian Fish, I took up the challenge with the determination of the dung beetle I observed while waiting for a tug on my fishing line this morning. The dung beetle was rolling its precious dung up an incline, which, from their perspective, must have been a very steep hill but appeared to me as an impressive anthill teeming with fire ants. The little ones were creeping all over the beetle, slowly but surely consuming it as hundreds of little ants injected their acid into its protective shell; yet, the beetle persisted.

*our hero; one with nature

*our hero; one with nature

“That is one determined dung beetle,” I thought as my line suddenly became taut and my nose twitched and my ears perked up. A bite!

Instantaneously flipping my baseball cap into serious-mode: backwards, I jolted up like a reverse thunderbolt and took on a sumo stance before clasping both hands on the grip of my fishing pole and pulling back with all my might. The line became tighter and tighter before reaching critical tension – a fierce tug of war then played out between myself and my submerged prey. “This one’s tough – maybe it’s the Guardian Fish!” I thought as I gave some slack on the line in an attempt to tire the great beast; Dad taught me well, and the fish immediately stopped tugging the line. “Now’s my chance!” I reeled in and pulled back as hard as I could, and… snap!

The line broke; my bait lost along with the hook now forever destined to be impaled in the fish’s mouth – a grizzly fate for a fish, trailing blood through water, attracting all manner of deep-water predators more deadly than the predator it was lucky enough to escape from – me.

Searching through my tackle box and suddenly I see: I’m out of bait. I have all manner of hooks but no bait. Then it dawns on me, Dad always said, “The perfect predator must be resourceful.” So, I look to the anthill; the ants had not yet managed to penetrate the dung beetle’s carapace of iron will, but the beetle’s body was obscured now: merely a moving ball of ants, likely in excruciating pain – I know! I’ll put it out of its misery!

I carefully pick up the dung beetle with two fingers, put it up to my lips and blow real hard; most of the ants go wild on the wind and I wipe the stragglers off with a few swipes of my index finger. The beetle’s legs continue to move, like when I used to hold my old dog over the tub before bath time – habitual movement, already paddling and still climbing up that hill.

Quickly, so as not to cause too much Suffering, I take my fishing hook and thrust it into the beetle’s soft white underbelly; it takes some small amount of force before I’m met with a satisfying crunch, what sounds like a sudden release of pressure, and a hydraulic stream of brown goo splashing upon the tips of my fingers.

The brown of the beetle drips down the hook as I sit down on the soft soil of the riverbank; lodging the grip of my pole into the dirt, as to keep it in place for a moment while I opened my metal lunchbox to take another bite – or three – of the crumbled rice ball from hours ago. But before I can take a bite, I hear something from behind me, a short huff of air, a low growl, and the pop of a jaw. My body stiffens and I freeze for a moment, a chill running through the entirety of my nervous system.

More big huffs, this time closer. It felt like another hour had passed in this terror-stricken state but in reality: only seconds. Dad always taught me to swallow my fear and deal with life head-on. So I take a big gulp of false-courage and twist my neck and I see it: fur so-brown-its-black fills my vision as my eyes creep upward, now staring directly into the hungry eyes of a brown bear intent on flesh, fish flesh or otherwise – me.

*the brown bear approaches

*the brown bear approaches

I must save Big Sis, even if it takes a miracle; and if God were a fish, He’d be the Guardian Fish. I’m fishing for God. This brown bear is not going to stop me.

The bear, with a demonic glint in its eyes, lifts its gigantic paws and quickly lunges at me. I think of my sister, and suddenly great courage is bestowed upon me from on high. I clumsily dash to the right, falling and rolling a few times on the verdant riverbank before catching my balance, one foot on the ground, one knee too. I remember the dung beetle; its determination. I grin to myself as I gather a clump of dirt in my right hand. The bear turns to me with surprising haste for such a big thing and starts at me once again. I throw the dirt into the beast’s face, halting it for a moment as it snarls loudly out of pure annoyance.

I take this opening to rush the bear head-on, ramming into its furry stomach before raising my fist and punching it right between its momentarily dirt-addled eyes. The bear flinches with a quick jerk of its head and then growls differently this time, a roar of pure malice; animal language more transparent than humans’, but I don’t care: I launch another punch into its stomach with my entire being; the bear counters, but I’m lithe, ducking and weaving so well that I catch only the tip of its longest claw on my shoulder, ripping my shirt and drawing a swirl of blood through the air.

I don’t feel a thing.

Determined to finish this, I push the full weight of my small body into the bear, which falls over with me into the grass below. I take my hands and put them around the bear’s neck, squeezing as hard as I can. The bear flails its claws wildly before settling on its signature attack: the bear hug; driving all ten of its claws into my back as if to absorb my very lifeforce. It must have missed my vitals because I was unfazed, and this only served to motivate me further.

I think about all the bears my Dad must have killed in his time as the River King. I must make him proud. I must save Big Sis, so I dig desperately into the bear’s neck, find the hard part – the windpipe, I hope – and squeeze as tightly as I possibly can. The bear intensifies its own squeeze in kind and I feel every inch of my clothes become wet with blood. I start screaming viciously as the fog starts to settle in; my vision blurs, my head fills with clouds.

Is this it?

Just then, God must have intervened: the bear’s grip loosens, and its growl becomes less murderous and more miserable before settling into a light gurgle. My face fills with foam as the bear tries, pathetically and in vain, to snap its great teeth into my face. Filled with a contradictory mixture of indignant courage, fear, and adrenaline, I loosen my grip on the bear’s neck and go all-in on its terrible visage, slamming the beast’s face repeatedly with my clenched fists; blood erupts like a primordial volcano with each blow. After what feels like minutes, I am crimson covered completely in bear blood.

Rolling off the beast onto the vermilion – once green – grass, I stare up at the clouds above, gasping for air.

My vision goes in and out as I lay splayed out on the riverbank. I hear crickets chirping, fish splooshing, bees bumbling, and limbs creak-cracking as squirrels play their tree games. I am reminded that I am still alive, and just as that revelation hits me, I feel a drip of liquid hit my cheek from on high – rain?

I open my eyes and the brown of the bear obscures my view once again. I hear – feel – the vibrations of the bear’s low, guttural growl. The beast is above me, looking down on its prey, a mixture of saliva and blood dripping from its mouth and onto my face.

Suddenly, it dawns on me: I never stood a chance.

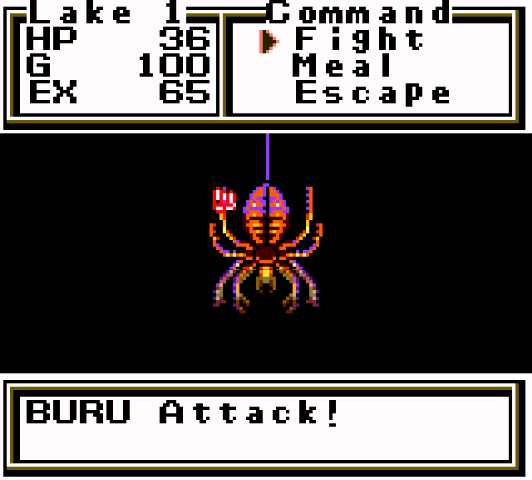

(This is it. I am not explaining, in any significant detail, how this computer game – Legend of the River King for Game Boy Color – is played, or its qualia, in this essay. I will say that everything in the story above is part of the computer game in question to some extent, and that most of it is facilitated by pressing the A or B button, or something; all the buttons kind of do the same thing: cast a line, reel in a fish, or make a menu selection in a random animal battle. It’s a lot like Animal Crossing if Animal Crossing were only fishing and punching the villagers, as River King’s fishing system is a clear inspiration to Animal Crossing’s and the villagers are, well, animals; if this sounds interesting to you, and you want a moderately chill fishing game to – as the kids say – “vibe out” in glorious GBC retro-stylings, then this is the computer game for you. On a side-note: if Legend of the River King for Game Boy Color does one thing successfully, it’s illustrating how in tune with nature – the ecosystem – humans actually are when you strip away their gizmos and gadgets; you fish, you sell or eat the fish, you punch animals in the face when they try to steal your fish. It’s “serious fun” which is also the publisher Natsume’s catchphrase (as seen on this essay’s titlecard). It’s interesting. It’s thought-provoking if you want your thoughts provoked. So, of course, the remainder of this essay is about how God is either A) Evil or B) non-existent.)

II: Holy Semantics and Theodicies

II.I: Foreword on Words

You may be asking, “What does Legend of the River King and the two-thousand-word story I just read have to do with God?”

And that’s a fair question.

The story above illustrates two things. First, the gist of the computer game in question; this is, after all, a video game publication and we – try – to stay on topic. Second, it highlights the brutality of nature and how just a few centuries ago the human race was subject to being easily mauled by bears, and most importantly: that many of us take for granted this simple truth, that we are part of our local ecosystem – the food chain – albeit now very-far-removed due to technological advances.

Instead of reeling-in the fish or hunting wild pigs ourselves, we now depend on massive cranes to hoist metal boxes and nets teeming with living beings which are then dumped onto conveyor belts, sliced up by unfeeling and indifferent automated-machines, and then neatly arranged in polystyrene trays for purchase at our local grocery stores – sometimes with a buy-one-get-one-free deal (appropriate, in this situation, that half of these dead animals are monetarily worth nothing, in-line with the figurative worth humans place upon them).

We constructed these systems of Suffering for efficiency and profit on one hand, and on the other, because most of us (myself included) are repulsed by the idea of personally inflicting this Suffering on another living being ourselves.

I apologize for the tangent, this essay is not about animal rights, ‘on computer games’ has plenty of essays on that subject already. This essay is about Suffering and why a supposedly all-powerful, benevolent God would allow Suffering to exist at all.

This essay will attempt to make the argument that God, in all likelihood, does not exist, but if He does: He’s Pure Evil.

*welcome to the food chain, sea bass

*welcome to the food chain, sea bass

Make no mistake, there is great beauty in the natural world – crickets chirping, fish splooshing, bees bumbling, and limbs creak-cracking as squirrels play their tree games; shimmering musical arrangements, sunsets filling the sky with orange-and-pinks, your first kiss, stars twinkling in the night sky, small smiles of newborn babies recognizing their parents; examples often used as evidence of an intelligent creator – “Who made these beautiful changeable things, if not one who is beautiful and unchangeable?” sayeth Augustine of Hippo – but what this fails to acknowledge is that for every beautiful element in nature there are horrors by the hundreds and endless amounts of Suffering.

Before making any argument, it is prudent to establish the definitions being used within the argument, otherwise semantic word games will ensue and no progress will be made. As such, this chapter exists to define the primary concepts I will be discussing during the remainder of this essay, as to prevent the figurative muddying of the waters.

II.II: Pray to the Monkey God

The history of ‘God’ is convoluted and, like our unfortunate River Boy, covered in blood. Generally, God is considered a supernatural being with super-intelligence that created our universe, either in full or in parts, depending on one’s belief system. We won’t cover every religion, as that would be a monumental task, but we’ll address the basic types of ‘God worship’ and establish the definitions relevant to this essay.

There are three important types of ‘God worship’: theism, deism, and pantheism. We’ll begin with the latter, which is the least important.

Pantheism refers to the idea that ‘God’ is synonymous with the universe or its governing laws or something. Many philosophers and scientists incorporate this concept into their work, exemplified by Einstein’s famous, albeit misquoted, statement: “I believe in Spinoza’s God who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists.” This understanding of God as the universe, collective consciousness, set of underlying universal rules to be discovered is more semantical than any other definition of ‘God’ in this essay, and arguably: just as harmful as the more conventional definitions as it clouds informed discourse and casts mass confusion on anyone not ‘in the know.’

For proof, look no further than the United States Constitution, authored by a group of wigged atheistic secularists. The Constitution states “One Nation Under God,” sparking debates and divisions since 1787,#1</sup as one faction believes it explicitly refers to the Christian God, while another contends that ‘God’ was meant as a pantheistic concept for the ‘universe’ or some vague notion of ‘whatever you want it to mean.’ The latter interpretation finds widespread support in the views of the founding fathers, who, again, were predominantly atheistic. Thomas Jefferson, a prime example, famously wrote to his nephew: “Fix Reason firmly in her seat, and call to her tribunal every fact, every opinion. Question with boldness even the existence of a God.” Despite this, atheists still can’t get elected into higher office and we’re still debating on whether creationism should be taught in public school. If the founding fathers had been clearer about their intentions – their definition of ‘God’ – perhaps we wouldn’t be as lost in the quagmire today.

In most cases, the idea of ‘God as the universe’ is used to placate an audience of genuine God worshipers who don’t know or care if you believe God is the collective universal laws of physics or hivemind of humanity so as not to reveal oneself as, really, just another plain old atheist; as long as you say, “I believe in God …” any obfuscation afterwards typically falls on selectively-deaf-ears that are far too dimwitted to decipher the word games at play.

Pantheism, as Richard Dawkins so eloquently put in his 2006 book “The God Delusion,” is just sexed-up atheism. At best, armchair philosophy or pretentious drivel aimed at pacifying the masses; at worst, intentionally dishonest word games that serve as a smokescreen for something else entirely. After all, why not simply say ‘the universe’ when referring to the universe? Why conflate a concept such as ‘God’ – widely believed to be an omnipotent super-intelligent being that intentionally created everything – with an entropic void of cool stuff? At this point, we could arbitrarily define ‘God’ as anything we wanted and it would be equally valid.

*pray to the monkey god

*pray to the monkey god

When people use the term ‘God,’ they are largely referring to a supernatural, omnipotent super-intelligence that designed, engineered, and created the universe and everything in it, including humanity. Sometimes this God resides within our material realm, sometimes outside of it; sometimes benevolent, sometimes not so much; often all-knowing on top of being all-powerful, and, if prayed to hard enough, may grant your wishes and, if their arbitrary rules are followed, may save your soul from eternal damnation (that they created) after shuffling off this mortal coil.

(As a side note, the currently popular Gods of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are depicted as masculine figures and, because of that, I will be referring to God with male-oriented pronouns for the remainder of this essay simply out of familiarity.)

Without diving deep into the waters of religion, of which there are many that claim God exists, and many that masquerade as religion but, in actuality, are philosophies of life (such as Buddhism). There are two main schools of thought relating to this omnipotent God: Theism and Deism; the former is utterly cruel while the latter is equally cruel just slightly more logical; an intellectual band-aid for some of the problems that pop up with true theism.

Theism, as defined by Oxford Languages, is “belief in the existence of a god or gods, especially belief in one god as creator of the universe, intervening in it and sustaining a personal relation to his creatures.” This implies that God created us and continues to meddle in our affairs. He is very invested; and in most cases, this God is described as benevolent, just, omnipotent, and omniscient. This aligns with the modern Christian belief in God, which I am most familiar with, considering Christianity is the most popular world religion with Islam trailing just behind it. Islam also falls into the theist category, albeit with a God portrayed as far more war-like and vengeful (yet still somehow benevolent).

Deism, alternatively, is defined by Oxford Languages as: “belief in the existence of a supreme being, specifically of a creator who does not intervene in the universe.” This is long-form for: God dipped like Dad after the divorce. This God might take the form of a ‘mad scientist’ archetype, who inadvertently created a universe, or an omnipotent being who chose not to intervene after creation (imagine creating the trolley problem then just walking away for the next unsuspecting person to deal with it later), or even a supremely intelligent force that simply exists in the background. The deist belief system handles contradictions of benevolence alongside Evil better than the theist belief system by saying “God doesn’t care about you because He went to the store to get a Four Pack of Tall Boys and never came back” but is still ultimately unnecessary and devolves into ‘God is basically the Big Bang’ and other pantheist word games when you start to think about it too hard.

In short, the definition of God we’re working with here is the God of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism; however, deist definitions of ‘omnipotent creator who dipped out’ or ‘pantheon of supernatural weirdos’ suffice as well.

Apologies you had to read all that just for it to be summarized so easily in one sentence.

II.III: Suffer Little Children

Suffering is pain.

Suffering is being plunged into boiling water; your skin burns as you gasp for air, instinctively trying to scream but the boiling water chars its way down your esophagus into your stomach where it bubbles-up the acid and tears holes in your stomach lining allowing the blood and pus to pour into your bowels and create a noxious soup of boiling decay; drowning and sensationally on fire simultaneously, arms flailing about, eyes expanding from the pressure and about to burst.

Suffering is not unique to humans. The lobster, hand picked from the grocery store by their new (and very temporary) family, knows this feeling of Being Boiled all too well, and although it cannot vocalize Being Boiled it can certainly flail about and exhibit every other sign of Suffering.

Nearly all animal behavior manifests to avoid Suffering, and humanities’ own great achievements have been for the sole purpose of avoiding Suffering as well. We’ve developed weapons to quickly dispatch predators, automated machines to make stuff we need for survival real-fast, fortified enclosures to protect us from ‘lesser animals’ and the elements, all manner of tricks and traps so that we’re not being sneaked-on; all to prevent lions, bears, and even other humans from mauling us and our children while we sleep.

Procreation may be the only thing animals do that doesn’t directly stem from this avoidance of personal Suffering and, in fact, propagates the continuation of the very Suffering we seek to avoid; although, the great joy children bring, biological or not, certainly helps us forget about the Suffering, regardless of how momentary that forgetfulness is. It makes sense, from an evolutionary perspective, for animals to reproduce to carry on their genes and continue the species, the orgasm response makes it pleasurable to do so, incentivizing us, and hormones throughout the body are there to give us that extra push; however, it only makes sense from a theological perspective if the God in question simply enjoys watching new creatures being born into Suffering – which is peak Evil behavior, identical to the forced birth of calves into pure Suffering at the local factory farm.

Imagine your firstborn’s head ripped off by a lion or a pit bull. You manage to escape, but the image of your helpless child looking straight into your eyes, depending on you to save them just before their gruesome demise as you watched, powerless to help, is now forever engraved in your mind. The lioness doesn’t have to imagine this because male lions kill their little cubs all the time; it’s just another day in the Sahara. Likewise with the momma cow at the factory farm, her little calves are killed right in front of her – by humans.

This is Suffering. Mental, physical. It’s hard to explain, but we all know Suffering on some level. Suffering is not The Cure in High School. Suffering is the very real and guttural feeling of ‘please just end it all, now’ and those things that take us ever closer to the edge.

Everything we do is to avoid this feeling of Suffering.

*a fish about to be caught and eaten; it can’t tell you “stop!” so, don’t worry: it’s ok

*a fish about to be caught and eaten; it can’t tell you “stop!” so, don’t worry: it’s ok

Animal Suffering and human Suffering are often separated, but there’s no difference; we separate them so we can feel better about all the terrible Suffering we inflict on non-human animals. However, humans aren’t the only creatures that inflict Suffering on other beings; we shouldn’t allow other animals to get a pass. It’s all intrinsically connected and nothing is above it, as vividly illustrated by The Boy and the Brown Bear. Both humans and non-human animals are part of the same system of Suffering we call the ecosystem. It’s a matter of kill or be killed, evident across all aspects of life; and sometimes, animals cause Suffering merely for the fun of it – religious zealots call this God’s gift of ‘Free Will.’

Snakes with venom that paralyzes their victims allowing the snake to slowly consume their prey’s body inch by inch; people loitering at truck stops off the interstate to find out-of-town victims to rape and murder; lions taking over rival packs and eating all the little cubs; Chinese water torture; Guantanamo Bay; the Gombe Chimpanzee Wars; brain-bolting cows at the factory farm; female spiders eating their partners after sexual intercourse; Vietnam rape babies; dolphins that kill porpoises and bounce their bloody carcasses through the air with their noses like circus balls; humans just eating each other because they can.

This is all very extreme, isn’t it? Let’s take a step back; back to the basics of simply looking out the windows of our comfortable homes. The grass is eaten by the rabbit; the rabbit is eaten by the fox; the fox is eaten by the wolf; and the wolf is hunted by the human. Each step (apart from the grass) has an element of Suffering – of Being Boiled.

The food chain is a cycle of Suffering and Suffering is synonymous with life itself.

And this is all part of God’s design; but, for an omnipotent and – supposedly – benevolent being: why are the basics of the universe contingent on Suffering? Why is Suffering hard-coded into the system?

Was there truly no other way to create life?

II.IV: The Problem of Evil

Before we can tackle the ‘Problem of Evil,’ we must first define what ‘Evil’ actually is. Evil, as a concept, is a loaded term and has been hotly debated since the beginning of human civilization, with an infinite outpouring of ethical systems attempting to establish some barrier of entry for Evil: consequentialism, utilitarianism, deontology, virtue ethics, ethics of care, egoism, social contract theory, moral relativism, and, of course, religion (perhaps the most powerful of them all, at least in terms of mass appeal). Many of these do not outright state ‘this is what Evil is,’ but they do attempt to establish some line in the sand of which crossing is a violation of the ethical system, typically leading to a reduction in the overall well-being of the person or society as a whole.

I want to clarify for the audience that I lack the level of intelligence (or any) to cover truly new ground in these ethical debates on what constitutes Evil, but that isn’t the purpose of this essay. I only need to touch on some semblance of ‘Evil’ to prove my point.

For the purposes of this writing, we will define ‘Evil’ in layman’s terms, as basic as possible: unnecessary Suffering. If Suffering can be avoided, yet it is not, and the problem is never addressed, that is Evil. If one takes pleasure in inflicting Suffering on another, that is Evil. Killing outside of self-defense is Evil. The Holocaust was Evil; The Crusades were Evil; The Little Boy and Fat Man were Evil; all three events were unnecessary applications of Suffering on countless innocent people.

Suffering, as outlined in the previous section, is all around us. We deal with it every day, from minor forms of Suffering such as stubbing our toes, to major forms of Suffering such as losing loved ones or getting mauled by bears. It makes sense that some people retreat into drugs and alcohol to avoid this Suffering; retreating into Suffering disguised as temporary bliss that just leads to even greater long term Suffering. It’s Suffering all the way down, baby.

Evil is the unnecessary and unsanctioned infliction of Suffering on another living creature. I recognize that this opens the door for a lot of ethical questions that could be debated endlessly, but that’s not the point; the point is the semblance of Evil, which we have just barely grazed the surface. And while there are arguments that can be made for ‘greater good’ applications of Suffering, Evil itself is always paired with Suffering; the two cannot be separated.

Suffering is not always Evil, but Evil is always Suffering.

*huh, i wonder why?

*huh, i wonder why?

Why would an omnipotent, benevolent God allow evil into the universe they created? Assuming we use the commonly accepted definition of ‘benevolent,’ then the answer is simple: He wouldn’t. He would have created the universe in such a way that Suffering would not need to exist.

He’s all-powerful, for God’s sake!

If God made the universe as we know it today, then He is not benevolent. God, being omnipotent, had a choice: create a world without Evil or create a world with Evil; God chose the latter, and in doing so, shows us that he is the source of Evil and is, therefore, Evil itself.

God created Suffering. Evil is Suffering. God is Evil. Japanese role-playing game protagonists knew this a long time ago.

Of course, religious zealots do not like this idea of ‘God is evil’ one bit and will do anything to counter it. There are two primary arguments that attempt to reconcile ‘the problem of evil’ with a benevolent creator God. Arguments of this nature are called ‘theodicies,’ or: “the vindication of divine goodness and providence in view of the existence of evil.”

The first is the ‘Irenaean theodicy,’ which posits that while evil exists, it’s not God’s fault because He made the world in such a way that Free Will and Evil exist to ‘develop’ humanity. Almost like the ultimate test; instead of just giving you happiness, He makes you work for it. This theodicy states that God created a world that is ‘the best of all possible worlds’ that allows humans to ‘develop into their full potential,’ but this begs the question: what is the worst of all possible worlds? And, what are humans’ full potential? And why is the latter important at all, what measure of value are we using to determine human potential?

“God gave us Free Will and there are consequences to Free Will” is the common Christian retort. But, an omnipotent benevolent God could have made us Some Sort of Spirit Stuff that has no Free Will, simply awareness and going-through-the-motions to make Suffering a non-starter. God could have blessed humanity with a perpetual state of bliss, but instead chose to test humanity by granting them Free Will and hoping we would choose not to harm one another and other animals in the cycle of Suffering we call the ecosystem. God, in the religious zealot’s mind, created Free Will to satisfy humanity’s ‘potential’ and God-given desires, but this Free Will has resulted in great Suffering for all life on the planet.

“Free will … pitiful humans … war, segregation, hatred – is that what you’ve done with your ‘free will,’ boy? Don’t you lecture me with your thirty dollar haircut.”

Not only would this hypothetical ‘Some Sort of Spirit Stuff’ creation method prevent Suffering, but it would eliminate the need for a physical body, which causes great amounts of Suffering through disease and aging. And if this seems ridiculous, remember: God is all-powerful. He could have created this hypothetical universe in which we are Some Sort of Spirit Stuff, among a number of other unimaginable universes in which Suffering doesn’t exist, but He chose not to.

*instead of Some Sort of Spirit Stuff, you are a human punching spiders

*instead of Some Sort of Spirit Stuff, you are a human punching spiders

The second argument opposing the ‘problem of evil’ is the ‘Augustinian theodicy,’ logically weaker than the previous theodicy but worth discussing because it’s the most commonly used argument by Christians to defend the presence of Evil in the world by blaming it, pretty much, on women. It essentially states: God is omnipotent and omnibenevolent, but he did not create Evil, He simply created Free Will and Humans mucked it all up: “Eve ate the apple from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil and that created Evil – not God!” Cool story, but God created Adam and Eve and the Apple. “But humans have Free Will!” Yes, but that Free Will was granted by God; “But the Snake tempted Eve!” Yes, but God created the Snake and the Snake – Evil personified – was a denizen of the Garden of Eden since creation.

The God of the Old Testament gets around this ‘problem of Evil’ somewhat, as He was never explicitly stated as being benevolent, which helps the arguments here a bit by essentially saying “yep, God is Evil,” but Christianity comes along and retroactively tries to ‘undo’ all the bad stuff by repurposing God as an omnibenevolent creator, implying some sort of ‘character arc’ for God in which “yeah, He was real mean back in the day, but He’s a good guy now because He sent himself down to Earth and killed Himself to save humanity” because, for some reason, He couldn’t save humanity by simply flexing His omnipotence.

This is all well and good, but an omnipotent all-knowing God should never have to undergo a ‘character arc’ for self-improvement – that would already be baked in – and numerous Ancient pantheonic Gods went through similar character arcs, and we, as a society, no longer give holy credence to Greek, Roman, Norse, or any other pantheon of ancient Gods. For some reason we have decided that those old religions are not valid, but our shiny-new religions are.

“The religion of one age is the literary entertainment of the next.”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

I recognize that these arguments do not disprove the concept of a creator as a whole; they simply highlight how contradictory and illogical modern concepts of benevolent, omnipotent Gods and their accompanying religions actually are. There is still wiggle room, logically, for a creator here, but there won’t be for long.

III: Addressing Each Argument for a Creator or: Dismantled King is Off the Throne (There’s Nothing Left)

III.I: The Ontological Argument

Originally proposed by Saint Anselm of Canterbury around 1040-something AD, the ontological argument for God is the idea that ‘if you can think it, it’s real,’ and, yes, it’s as moronic as it sounds. Saint Anselm of Canterbury essentially states: since it is possible to imagine a perfect being, such a being could not be perfect unless its essence included existence, and whatever that perfect being you are imagining right now is, God is likely much greater than that. Therefore, God exists?

This argument is problematic for a few reasons; first, I can imagine all sorts of things, doesn’t make them real; just open a Dungeons and Dragons handbook and flip through the bestiary. If this argument (really just a word game) were true, all those DnD monsters would exist, somewhere, in the universe. The second issue is that it’s purely semantics, what is ‘perfect’ anyway? How do we define perfect? Can we – truly – imagine a ‘perfect’ being at all? Why are we also assuming that ‘existence’ is more perfect than ‘non-existence?’

Alas, while I wish I could simply will things into existence with brain-power alone, I am not that special, and am certainly not one of Professor X’s mutants.

This argument is like fishing for God in an empty bathtub.

III.II: The Cosmological Argument

This argument is as old as the Greek philosopher Plato himself, going back as far as 400 BC (or something). The Greek philosopher proposed a ‘first cause,’ stating that all motion in the universe must be ‘imparted,’ implying an initial cause is needed to set a series of events in motion. Fast forward to 360 BC, in one of Plato’s dialogues, “Timaeus,” he suggested, through the titular character of the dialogue, that a super-intelligence could possibly be the ‘first cause’ of the universe – ‘the demiurge’ – hypothetical within the context of the dialogue. Christian fundamentalists, however, are not so hypothetical and insist that this ‘first cause’ had to have been their creator God, Yahweh, and that there is absolutely no doubt about it.

The counters to this argument are obvious, and something my dimwitted middle school brain conjured up way before I even had access to Goth music and Wikipedia; the obvious questions are still obvious and they cannot be hand-waved away so easily: if God created the universe, and everything needs a first cause, then who or what created God? What created the thing that created God? Is it Gods all the way down? Are Kings continuously dismantling each other from the causal throne? If so, how does this prove that a true ‘first cause’ exists at all, and is not just an infinitely recurring loop of creators?

If we grant that there is a true first creator, how do we know this first creator is actually the Christian God and not the God of Islam, or Zeus, or Captain Picard accidentally creating a universe-birthing bootstrap paradox through reckless use of time travel?

If everything needs a ‘first cause,’ allowing one thing without cause to exist is a contradiction unto itself; additionally, there is no reason why ‘the universe’ itself cannot be the first cause, as that seems just as valid as ‘God.’ And no, this is not pantheistic reductionism, just simply that either could be the first cause; it’s arbitrary.

III.III: The Designer Argument

“But the universe doesn’t have intelligence! How could it possibly create cute puppies all by itself? It’s just an entropic void!”

Like aesthetic sweatshirts and cool computer games, surely, the universe must have a creator out there somewhere, right? These computer games cannot be this cool without a super intelligent designer creating them!

Welcome to ‘Intelligent Design’: the idea that all life on Earth just seems so aesthetic and well-designed that it must be created by an intelligent designer. This idea is as old as time, as it is anthropocentric simply by virtue of humans existing and projecting our stupidity onto the world around us, but was popularized by Thomas Aquinas, a 13th-century Catholic theologian. Aquinas, in his “Five Proofs” (for aesthetic sweatshirts and cool computer games), stated: “Wherever complex design exists, there must have been a designer; nature is complex and therefore nature must have had an intelligent designer.”

My first counter would be, why one designer? This argument is always presented with a singular designer, yet, in our anthropocentric worldview, doesn’t it make more sense for the creator of the universe to actually be a group of creators considering its perceived complexity? After all, most of humanity’s great achievements were created or compounded upon by multiple people. Perhaps one designer did the gravitational forces and another did the stars, while another designed humans and another designed cats and dogs?

Perhaps the Romans were onto something.

Secondly, regardless of plural or singular designers, they did a poor job either way. Why did they place humans on such a hostile planet in direct view of the sun, which produces rays that burn our skin and can potentially kill us? Wouldn’t they have been a bit more considerate of our bodily needs if we’re their prime specimen?

The human body, for example, has a number of useless parts: the appendix, palmaris longus muscles, wisdom teeth, male nipples, and – sometimes – even vestigial tails. If the designer(s) are so intelligent, why do we have these parts? This is not just a problem for humans; it’s all over the animal kingdom. Why should moles, bats, and dogs possess useless forelimbs or dewclaws, for example? These useless body parts, theorized to be used by ancient ancestors for something or other, point more toward a progression of complexity rather than an initial intelligent design. And while this essay is not a defense of the theory of evolution, evolution solves this problem far better than “the all-powerful super intelligent God(s) just slipped up during character creation.”

And in some cases, things are just too complex. Taking the ‘Some Sort of Spirit Stuff’ concept from the previous chapter: why do living creatures need bodies at all? Why do we need sustenance? Why do plants need water, sunlight, and carbon dioxide to create oxygen? Why must this oxygen exist to ensure animals survive? The whys are endless. It appears more so that these ‘rules’ developed slowly through a natural process rather than Gods designing them all with the highest magnitude of complexity in mind.

The world we live in is incredibly complex, and complexity is not necessarily intelligent by default; an intelligent designer, especially one that is all-powerful, omnipotent, and super intelligent would incorporate far more simplicity in their designs.

And, like each argument for God, even if we grant that ‘Intelligent Design’ is true (I am being very generous today), it still does not answer a very important question that has kept people killing each other for thousands of years, and that is: which intelligent designer actually designed everything?

III.IV: Occam’s Razor

Thomas Aquinas would later employ the principle of parsimony, an early phrase for what we now widely term ‘Occam’s Razor,’ as one of his proofs for God. Occam’s Razor, a concept coined by William of Ockham in the 14th century, borrowed from the parsimony principle and states: “when explaining a thing, no more assumptions should be made than are necessary.” Essentially, it suggests that the simplest explanation is usually the correct one. However, concluding that a specific God created anything involves a plethora of wild assumptions. You would need to assume the existence of a creator of significant power to single-handedly create the universe, assume it’s power source, assume it’s own creator, assume the anatomy of this being (assuming they have one at all), assume their location, and assume their intentions. The list goes on.

Occam’s Razor serves only to guide someone in the right direction for worldly endeavors, suggesting that perhaps their first impression was correct: “the cookie jar is empty, and my son has crumbs on his shirt, I wonder who took the cookies?” It can never be used as de facto proof of anything because empirical evidence is still required – of which there is none for God.

III.V: The Designer Argument Pt. II

Some theologians take ‘Intelligent Design’ further, applying it not just to biological life but to the observable universal laws. They argue that the forces of physics, the arrangement of stars and planets seems so finely tuned to allow for the creation of biological life that it cannot be random; they charge that the universe is a puzzle that cannot magically solve itself, but then turn around and attempt to solve it through their own magic – God.

*could this super aesthetic computer game come into existence without a creator? checkmate

*could this super aesthetic computer game come into existence without a creator? checkmate

Why can’t it be random? We may not know the exact cause of the universe, but not knowing something doesn’t suddenly make every competing theory true – that would imply every religion is correct, and that’s a problem as every major religion claims they’re the only correct one. However, I will admit that this argument is the strongest in that there is a gap here – we do not know how the universe was truly created, and this gap can be filled by anything, but what is the probability that your one religion, out of thousands, is the correct gap-filler? Especially considering that there is no empirical evidence suggesting that any religion is even close to the correct answer?

The measurable universe is very old (13 billion years old, or something), and we lack an understanding of what preceded it. There was ample time for something – anything – to occur, and evidently, something did occur. With an infinite amount of time, countless possibilities emerge, potentially offering infinite chances for life as we know it to form. An infinite number of random computer games and Boltzmann’s brains; all this proves is that something happened; this does not prove an intelligent creator, let alone a specific deity from a Holy Book. It merely suggests that given enough time, life emerged, and we’re the ones experiencing it. Labeling it ‘God’ circles us back to the cosmological argument of Dismantled Kings of First Causal Thrones.

To break free from a recurring causal loop, one might argue that God exists outside our material universe, beyond the realm impacted by the ‘first cause’ requirement. However, this idea is unfalsifiable and lacks any evidence. Furthermore, even if we accept this notion, God’s nature, as discussed in Chapter 2, is still incredibly Evil due to the problem of Suffering and does not deserve to be worshiped.

You can’t have your cake and eat it too with this one; either God created everything, including Evil, or He didn’t create anything. Given the substantial mental gymnastics required and the lack of palpable evidence for God’s existence, finding solace in the concept of His nonexistence is reassuring; it means that there isn’t a mysterious malevolent force constantly evaluating our merit through the infliction of endless Suffering, all the while ignoring all prayers directed to Him – why would He respond to prayer anyway? He’s Evil.

God is like that high school ex who, when you rang them late at night, never answered the phone; instead, they kept count of how many times you called while they played computer games, using the missed-call-counter as a measure of your love for them – if you didn’t call one night, they’d immediately call you the next day, angry: “why didn’t you call me last night? Where were you? You’re cheating on me, aren’t you? Prove you’re not cheating on me right now!”

That ex was actually me – I was an asshole in high school, but the comparison remains unchanged.

III.VI: Argument From Religious Experience

“To me, it looked like a leprechaun to me – all you gotta do is look up there in the tree. Who else seen the leprechaun, say yeah!”

The argument from religious experience is something along the lines of: “I saw Jesus’ face in a piece of toast!” or “God spoke to me and told me to stop eating gluten!” or “I prayed really hard to God and Mom recovered from cancer!” or the more serious, but often arbitrarily hand-waved away by ‘true believers’ because it makes their religion look bad: “God spoke to me and told me to kill all the people in the Mosque.”

Regardless of the obvious delusions, a surprising number of religious people use this argument of personal experience to justify their belief in God. Proponents of this argument are the most dangerous of all religious believers because their faith is based on unfalsifiable personal experience, and they double down on that fact – they don’t care if they can’t prove it to you; they just know they’re right. These types of beliefs should be treated with extreme skepticism, as this line of reasoning can potentially be used to justify all manner of nasty things because “God told me so.”

Like the Mobile Leprechaun, these people saw something – possibly a limb casting a shadow that looked kinda like Jesus’ face when walking home late at night after a few drinks at the bar. These people are the type to, upon seeing something mysterious that vaguely aligns with their already held personal beliefs, wear ratty clothing “passed down for generations” because they believe it “wards off spells” and use a flute they believe plays holy notes that banish demons, which is actually just a piece of PVC pipe they found in their backyard (a sun ray was hitting it in a curious way so, of course, this was taken as a divine sign from God that it was an instrument of the angels).

The joke, if you haven’t picked up on it already, is that there’s no difference in believing you saw a leprechaun or Jesus’ eyes move in a painting one time thereby affirming your love of Christ. Correction, there is one difference, religious-delusions are socially accepted at the moment while leprechaun-delusions are not, despite both being hallucinations brought upon by a lack of critical thinking, brain trickery and, in the worst cases, true mental illness.

Have you ever heard whispering late at night, searched for the source, and found it was just the wind? If you were a religious person, imagine what kind of words you might hear on that whisper-wind? Have you ever looked down a long stretch of road in the blazing heat and seen what looks like wavy pools of water? Perhaps if you were a religious person, traveling the desert sands, you may see this as a gift of water from God, just a mile or so out of reach? Optical illusions, auditory hallucinations: the senses play tricks on us; filling in the blanks and sometimes just making things up.

*stereogram; can you make out the words hidden within the optical illusion?

*stereogram; can you make out the words hidden within the optical illusion?

In a world where we still debate whether one person’s perception of the color blue is the same as another’s, it is truly astounding that anyone would take an argument based solely on subjective perception seriously for anything.

III.VII: Argument From Morality

“But without the fear of God, people would start murdering each other! It would be chaos!”

The “Argument From Morality” is the claim that religion, especially Christianity, has provided a strong moral base for society as a whole, from the moment Moses – supposedly – came down from Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments. This moment suddenly stopped people from raping, murdering, and stealing; wait, people are still raping, murdering, and stealing – aren’t they?

You’re right, that’s unfair. It’s what we in the Big Brain Business call a ‘strawman argument’ (this is self-deprecation, not actual egotism).

The claim isn’t that religion stopped these occurrences, just that it curbed them, reduced the God-given Evil that humans do with their God-given Free Will – almost like God said: “oops, I messed up with this Free Will stuff – here, follow these rules instead.”

Essentially, this argument boils down to: if we didn’t have religion to guide (scare) us, we’d be committing far more atrocities than we do now. This, of course, ignores the countless historical atrocities committed in the name of religion. The extreme angle of this argument is that “God literally made the morals,” which, again, is Evil (or pure stupidity, which is often indistinguishable from Evil) for the reasons illustrated in Chapter 2.

Like the other arguments on this list: problems galore. The first is a problem of logic. Even if we grant that religion has curbed rape, murder, and a variety of other Evils, this doesn’t prove the supernatural claims of the religion; it simply proves that the religion’s moral system produced favorable outcomes. It says nothing about the literal existence of God. You would have to make a Grand Canyon-sized logical leap to say that one random thing (an ethical system) proves some other completely unrelated thing (YHWH’s existence) by virtue of them being in the same Old Desert Book.

The second problem with this argument is a question of honesty and another ‘Problem of Evil’ type question that boils down to ‘why would a benevolent God give us faculties to commit such atrocities to begin with, give us rules not to do it, then punish us if we break the rules?’ Additionally, if the claim is that ‘people don’t murder because they are afraid of God’s wrath,’ that implies people still want to murder but are ‘holding back’ because they don’t want to be lightning-bolted by a supreme being. First, a God that demands worship out of fear is not a Good Dude, and second, this fear-based system doesn’t provide sufficient logical reasoning as to ‘why’ people should not murder to begin with – it’s simply because ‘God said so.’

People ought to be provided enough logical reasoning to come to the conclusion themselves that murder (and many other violations of autonomy) is bad without relying on a supernatural deity. Implying that we need to force a Godly Thunderbolt into someone’s brain to make them see reason is, frankly, insulting to humanity as a whole – yes, we’re dumb, but I don’t think we’re – that – dumb.

This takes us into our final, and certainly most important, problem with the ‘Argument From Morality’: if God is the headmaster of morals instead of logic, what happens when God’s rules change? And secondly, what happens when one religion’s rules conflict with another’s? Ideally, the Holy Book is unchanging, but due to age and style of writing, much is up for interpretation. Look at Judaism, it branched off into Christianity once someone wrote a sequel to the original after Some Guy was very convincing about being the ‘Son of God’ (or literally God, or something), and it also branched off into Islam later on. Christianity branched off into hundreds of denominations with different rules and beliefs. Islam has multiple branches as well, including the Sunni and Shiite branches, which have been the cause of countless wars and acts of terror in the Middle East ever since.

In the simplest of terms: each religion has its own rules, and those rules often conflict with each other. Using religion, there is absolutely no way to reconcile conflicting morality systems. In an extreme example, if one religion’s moral system is to “kill all infidels and their children,” and this is a God Given Decree, how do you argue against that? Yes, you could say their God is wrong or does not exist, but to the true believer: It doesn’t matter, your head is coming off and your baby is being thrown against the rocks.

“Happy shall he be, that taketh and dasheth thy little ones against the stones.”

– Psalms 137:9, King James Version

These rule-conflicts lead to war and strife because there is no reasoning with “these are literally God’s rules, you must obey them!” and “No, your God’s rules are wrong! You should obey my God’s rules instead!”

With a logic-based ethical system, such as ‘The Golden Rule,’ it’s far easier to reconcile ethical dilemmas. Now, ‘The Golden Rule’ is not perfect, and ethical systems branch off into just as many denominations as Christianity, but almost all of them agree that killing people indiscriminately is wrong and can work backward to tell you why. We don’t kill people because it’s a violation of bodily autonomy; imagine yourself as the target of your own murderous rage, would you want to be murdered? Why not? Because you want to live. This is a baby-tier preschool-level example, of course, and there are more complicated situations, but those of a logical mind can sit down and reason things out with the opposing side; differing religions cannot do this because they have a ‘benevolent’ and ‘infallible’ God making all the rules, and those rules are unquestionable to the true believer.

When it comes to religion as an ethical system: reasoning and logic go to the wayside and suddenly: you’re bombing a Mosque.

IV: Conclusion or: Fishing for God

My mom is a fairly religious person, a Christian who sometimes attends church, but mostly just stays home gardening and watching Bill O’Reilly (or whoever his current clone is now) on Fox News; an armchair Christian, but still a believer. She never shoved religion down my throat or made me attend Sunday service; this likely contributed to my telling people that I was an atheist even from the young age of ten. I was afraid to tell my parents, at least early on, but I remember telling my friend near the fishing pond in our backyards one youthful summer; he was briefly shocked, then we quickly decided to go back to Ding Dong Ditching homes in the nearby cul-de-sac. It never came up again until years later when he, too, told me he was an atheist.

I wish I could say I was ahead of the curve. I wasn’t; I was simply a contrarian from a very young age and still have some of that contrarian edge even now, for better or worse. However, now, I don’t even know if I would call myself an atheist. I resonate more with the label ‘agnostic,’ but only from a strictly “yeah, maybe it’s possible – but I don’t see any evidence to indicate that it would be right now” perspective. This branch of agnosticism, or atheism (depending on who you ask), is called ‘agnostic atheism’ and is, in this writer’s opinion, the most honest position one can hold on the matter at this juncture in space-time. There’s no evidence for God(s), but humans aren’t all-knowing – we could discover hard evidence; it just hasn’t happened yet. There’s also no evidence for pink unicorns, and I wouldn’t say I’m ‘agnostic’ on pink unicorns, but I would say this about ‘God’ because the problem of creation is still ever-present in the world of science, leaving room for a potential ‘God sneak attack’ – although, again: which one?

Around fourteen or fifteen, I finally told my mom that I didn’t believe in God. I have a fairly poor memory, but I remember this clearly; she was driving me to the pier (we lived in an island community in Georgia) to meet some friends when a radio commercial about some local church fundraiser started playing from the car speakers. This triggered my figurative fedora so I turned to Mom and told her, pretty much, that I didn’t believe in God. She smiled, not upset at all, and responded with, “I know.” How’d she know?

Then Mom made a little joke that stuck with me for the rest of my life, “sometimes I pray to every God, just to be safe.”

This was not laugh-out-loud funny at the time, but it was thought-provoking from the perspective of – wouldn’t that be impossible? The absurdity of the comedy revealed a fundamental contradiction about the nature of religion – the existence of other religions undermines the validity of those religions – and it’s a joke I still tell to this day, hoping others may get something out of it in the same way I did as an edgy teenager.

Let’s pretend everything in this essay is incorrect; all the logical deductions made are false, all the religious atrocities and Suffering excused – let’s pretend that God does, in fact, exist, in some form or function: well, which God is it?

How do I know which God or Gods to pray to so I don’t end up in The Bad Place after I die?

Is it a pantheon of Gods? The Zeuses, Wodans, and Athenas that created and govern only certain aspects of the physical world but still demand tribute and worship?

Is it the mad scientist God of deism? The omnipotent God that created everything then dipped like Dad after the divorce?

Is it the theist God of Evil masquerading as a benevolent God? The omnipotent, all-knowing creator that conjured everything into existence, including Suffering and Free Will, then obscured Himself from humanity and asked us to believe in Him on faith alone with the punishment of eternal damnation if we don’t? If so, is it Yahweh, Allah, Jehovah, Isvara, or maybe: the Guardian Fish?

*has all our fishing finally paid off?

*has all our fishing finally paid off?

We don’t know how the universe was created. We don’t know if there’s life on other planets. We don’t know if the mind controls the body or the body controls the mind. We don’t know why Big Sis got cancer and died suddenly.

We don’t know what – if anything – happens when we die.

We don’t know what lurks in the deepest depths of the ocean – but perhaps with a good enough fishing rod and long enough line, we’ll catch God – maybe then, all of our questions will be answered?

Footnotes:

#1. Correction; as pointed out by Mastodon user John Chapman: “the original Constitution said “One nation”. The phrase “under God” was added in 1954 by an act of Congress[iii] at the urging of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was responding to citizen petitions.” Correction continued; “One Nation Under God” is not in the Constitution at all, it’s in the Pledge of Allegiance (which is what Eisenhower had updated); either way, the point surrounding the vagueness of the meaning of “God” in the Pledge or the Constitution or otherwise is still holds.

(Originally published on 11/19/2023)

#ComputerGames #Religion #Ethics #LegendOfTheRiverKing #Essay