Game Over, a Popful Mail Thing

I, POPFUL PRELUDE or: Retroism Realized

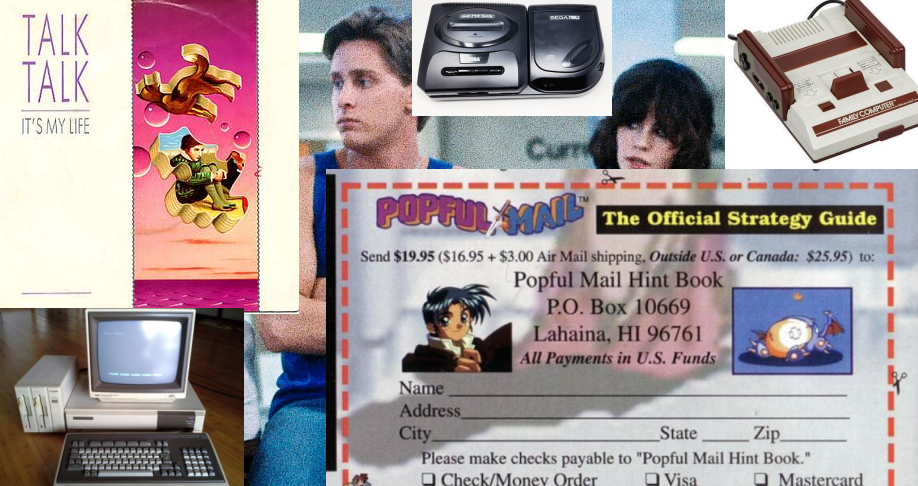

The Sega CD was released in Japan in 1991 – a very long time ago, 31-years-long-ago, to be exact. I was barely even born at that point, not having truly been born until 2013 when I learned the true meaning of life (that there is none) and only physically born a few months before the Sega CD. And, despite knowing this in the recesses of my mind but always being surprised when remembering, the Nintendo Entertainment System, or the fancily named Famicom, came out in 1983 – one year before my favorite song, Talk Talk’s “It’s My Life,” and two years before Simple Minds’ “Don’t You (Forget About Me),” a song that, while incredibly popular because of The Breakfast Club, is just not that good and frankly kind of annoying with its melodically flat and monotonous chorus. Even crazier still, the NEC PC-8801, hardware Nihon Falcom’s Popful Mail was originally developed for, was released 41 years ago. The point is, this stuff is old – very old; Dad-had-a-mullet-old.

One might wonder: why play this old stuff? What’s the point? Well, as Dad always says, things were just better “back in my day.” Back then, platformers dropped you from a ledge and laughed; nowadays, weird sugar glider creatures fly in from off-screen, grabbing your character, placing them back on the ledge right before the fall, sometimes even offering to complete the jump for you – because if one thing makes a computer game better, it’s the ability for the computer to play the entire game for you. Humans not required.

Is one game design philosophy better than the other? It’s all a matter of opinion, but not really; because objectively, yes – one is better than the other: the one that doesn’t erase every dumb mistake you make, like rich parents who donate heinous sums of money to the local police department; above the law, and apparently above the tedium of actually playing computer games.

The game design philosophy favoring difficulty over automation, of course, comes with the existential dread of questioning the worth of video games altogether while pondering the time you’ve wasted mashing buttons on a controller; after all, you could have been doing something productive with your time, such as going back to college or earning a real estate license – even Dad cut his mullet at some point. But me? No – I refuse. I’m growing it out.

So, of course, I play old stuff. I play old stuff for the same reason I have a vinyl record player: so I can throw on the 7″ of “It’s My Life” while I rant to my wife about how overrated The Breakfast Club is, all while proclaiming Purple Rain the definitive ’80s movie. I wax nostalgic. I pine for a time I don’t remember, a time when getting the strategy guide for a computer game involved cutting out a card from the game’s official manual, sticking it in an envelope, mailing it off to the publisher along with $20, and then waiting three months; old-fashioned wholesome transactional methodology made entirely irrelevant by the final boss of the internet: Bezos, or something.

But, do I really care about this retro idealism? Not really – I just thought it would sound cool for the article; maybe I cared a little when I was in my twenties, but now? Now I’m mostly driven by a strong aversion to change, with just a sprinkle of nostalgia thrown in for good measure; sugar, spice, and everything wrong with the human psyche: a lot of contrarianism.

*Talk Talk’s “It’s My Life,” Popful Mail strategy guide mailer, old consoles; Breakfast Club backdrop

*Talk Talk’s “It’s My Life,” Popful Mail strategy guide mailer, old consoles; Breakfast Club backdrop

Anyways, Popful Mail is a quirky side-scrolling platformer developed by Nihon Falcom, of Ys fame. Popful Mail was originally released for the NEC PC-8801 home computer in 1991, then re-released on the PC-9801 in 1992, then remade for the Sega CD in April 1994, then remade again for the Super Famicom in June 1994, then re-re-released on the PC Engine CD in August 1994, then re-released again on Doja mobile phones by Bothetc in 2003, and finally re-released yet again on Windows PCs in 2006. Each version differs slightly (or wildly) from the others, with only one version released in North America – the Sega CD version, which happens to be the focus of this article.

When deciding to port Popful Mail from the NEC PC-8801 to the Sega CD, Sega originally reimagined the game as a Sonic spin-off titled “Sister Sonic,” with the aim of capitalizing on the immense popularity of the spiky-blue-mammal franchise. This rework would retain the core gameplay of Popful Mail but replace all the characters with new Sonic sidekicks. Notably, Mail would be replaced by Sonic’s sister, a completely new addition to the Sonic series that surely would elicit multiple inappropriate fanarts found only in the nastiest corners of the internet – primarily DeviantArt. However, much to Christian Weston Chandler’s frustration, this reimagining never came to fruition, leaving Sonic’s long lost nameless sister truly lost to the annals of time, forever trapped within some dumb executive-in-a-suit’s binder full of dumb corporate-friendly computer game pitches.

In light of Sister Sonic’s failed localization, the publisher Working Designs stepped in; taking on the responsibility of releasing the game in North America. Under the leadership of Japan-centric director Victor Ireland, who made it his personal mission to bring obscure Japanese games to the West, Working Designs quickly established itself as a publisher renowned for high-quality English ports of relatively unknown series in the West; including Exile, Lunar, Alundra, and Arc the Lad.

While the bulk of Popful Mail for Sega CD was already completed, localization needed to occur for the English release. This is where Working Designs worked their designs, rewriting most of the script to be more humorous, recording over 2 hours of English lines, and reworking over 20 minutes of anime cutscenes. They even utilized waveform analysis to match the existing character portrait mouth movements to the new English lines, a process that took over 4 months. The results speak for themselves: the English dialogue and the more humorous direction fit the overall tone of the game extremely well. And despite the choppiness of the low frame rate anime cutscenes, they shine through as a highlight of the Sega CD version of Popful Mail, helping to establish its charm as a playable ‘90s anime.

*while the anime cutscenes are typically very few frames, they are all beautifully drawn and fully voiced in English thanks to Working Designs’ localization

*while the anime cutscenes are typically very few frames, they are all beautifully drawn and fully voiced in English thanks to Working Designs’ localization

Much like Cartoon Network’s Toonami, Working Designs’ willingness to take risks on peculiar Japanese media earned it a place in the hearts of young kids throughout the ’90s and early 2000s, shaping the aesthetic tastes of an entire generation of reclusive nerds and weirdos; likely including the demographic that would be reading an online gaming blog titled ‘on computer games,’ or, heaven forbid, writing for one.

As a preface, this article does not intend to be a comprehensive comparison between all versions of Popful Mail, as I have not played every version, and frankly, I don’t want to; however, there are three main versions of Popful Mail that are easily distinguished: the original NEC versions, the Sega CD version, and the Super Famicom version.

Sega and Working Designs are responsible for arguably the most popular Sega CD release of Popful Mail, which incorporated a number of significant changes. The most obvious being the name change from Poppuru Mail to Popful Mail, made simply because it was a better fit for the bubbly goofball tone of the game and its titular main character. Other notable changes include reworked graphics, updated sound design, and new gameplay elements, such as the inclusion of an attack button instead of the strangely counter-intuitive “walk into enemy to deal damage” combat system of the original NEC versions; and while the Super Famicom version includes similar changes, it deviates so much that it might as well be considered an entirely different game deserving of its own article.

*NEC & Sega CD Popful Mail compared; Mail pictured in the same area in both, illustrating the near 1-to-1 level design between the two versions.

*NEC & Sega CD Popful Mail compared; Mail pictured in the same area in both, illustrating the near 1-to-1 level design between the two versions.

The Sega fandom seems built around liking stuff – in spite of quality – only because Sega did it first, making the first fighting game or racing game or whatever – not unlike the person who prefers The Vaselines over Nirvana only because they inspired Nirvana, even though The Vaselines only have one semi-decent song (that song being “Jesus Wants Me for a Sunbeam” – and yes, that person was me in high school). I bring this up because whenever Sega CD is mentioned within the highly contrary Sega fandom (of which I’m being unfair and basing my entire analysis of the fandom on one insane acquaintance), Popful Mail is inevitably recommended every time; and considering its high praise, I had to play it myself.

To a lesser extent, “on computer games” needed an article covering a genre other than the role-playing genre; and before you leave a nasty reply proclaiming that Popful Mail is a role-playing game, let me clarify that Popful Mail merely pretends to be a role-playing game, incorporating only a few scant role-playing game elements; much closer to a platformer or Castlevania game than a role-playing game; an important distinction, as I firmly believe words and phrases should have meaning, and the term ‘role-playing game’ should have a clear definition. I am fed up with hearing how Zelda is “actually a role-playing game because you play a role and become stronger and stuff.”

Much like Popful Mail – short, sweet, silly, and not a role-playing game – this article intends to chronicle my experience with the Sega CD version of Popful Mail without being overly long or a chore to read; a rare occurrence for this site, known for long-form content and having no readers. Like all of our articles, this is not a review and it does not care if Popful Mail is your favorite game ever or whatever.

So, pass the aspirin and remember to abra instead of kadabra, because we’re going to talk about the game now.

II, TALKING ABOUT THE GAME NOW or: Goobers in a Nameless World

Popful Mail is a ridiculous computer game that evokes the feeling of playing a ’90s anime that doesn’t take itself seriously at all. It’s a goofy romp through a fantasy world full of swords and sorcery, where tanuki swordsmen and midget magicians roam giant tree forts with perfectly placed platforming logs, and the villain’s evil plot is often referred to as “crazy shenanigans.” In this nameless world, our hero, a bounty hunter named Popful Mail, hails from a town called Bountyville, which is blown up at some point by the dastardly wizard Muttonhead. Muttonhead is working alongside an evil puppeteer named Nuts Cracker, who has a detachable head and an almost-offensively-bad Italian accent. If none of this sounds absurd to you, it’s probably because you’re eight years old and shouldn’t be reading this article.

Popful Mail pretends. It pretends to be a role-playing game. It pretends to be an anime. It pretends to have a cohesive plot. It pretends to have important characters; however, the important bit here isn’t the absurdity of the setting or the characters but the namelessness of the world in which our heroes inhabit, illustrating just how unimportant the lore of this world is; lore being a key aspect in most role-playing games. Here, there is no world to reference; if you wanted to strike up a conversation about Popful Mail’s setting you’d have to use more words than you’re probably willing to invest – there’s no “in Tamriel,” only “in the world of Popful Mail,” a mouthful. And while this computer game does contain a prologue where seemingly important stuff happens, it doesn’t matter; as the famous Carl once said, “none of this matters.”

Popful Mail’s emphasis is on being a fun computer game, not on being a deep storytelling device with cool gods and clever world-building; none of that stuff matters – the world is nameless and the prologue is a pleasantry. The world, and the prologue, is there to facilitate the gameplay; as such, we have a fantasy facsimile; a generic world encompassing a forest zone titled “The Elf Woods,” two mountainous areas imaginatively referred to as “Mountains,” a polar penguin place creatively called “Chilly,” and a castle town complete with big tower that serves as the final hurdle of the game.

Each zone contains several levels, each with its own enemies, bosses, traps, and what I reluctantly refer to as ‘quests.’ Our heroes traverse these realms by traveling on a world map similar to the one found in Super Mario Bros. 3 – a world map where super-deformed representations of our heroes move from point A to point B, with each point representing a stage waiting to be conquered before our heroes can progress.

*the various zones of Popful Mail; showcasing the Super Mario Bros. 3 inspired world map

*the various zones of Popful Mail; showcasing the Super Mario Bros. 3 inspired world map

Our heroes form a triumvirate; each with different weapons, movement options, and personalities: the titular bounty hunter, Popful Mail; the aspiring wizard protege, Tatto; and lastly, a small blob of fat with wings named Gaw, belonging to the Gaw species, all of whom are named Gaw. Mail is available from the start, but the rest of the gang joins later after specific events. Each character is controlled separately and can be switched between at (almost) anytime through the pause menu, and as each character has their own health bar, you can switch between them when one gets low, effectively turning them into damage sponges when the need arises; however, if one character dies, it’s the game over screen – a screen you will be seeing a lot.

The magic happens when you interact with NPCs while controlling one of the three playable characters. Their distinct personalities shine through, leading to dramatic and often humorous changes in the way these interactions play out. Silly humor makes up the wit and soul of Popful Mail, and it’s overflowing in this regard. This is especially prevalent considering the number of absurd unskippable diatribes before boss battles, coupled with the fact that you will be dying a lot, forcing you to replay said unskippable diatribes; a major annoyance, but somewhat alleviated by the ample opportunities to see each character’s unique interaction with the boss.

Our titular hero, Popful Mail, is clearly based on the character Lina Inverse, of the light novel and cult anime series Slayers, which was very popular in Japan around the time of Popful Mail’s 1991 development. Both characters share the same design aesthetic, an excessively bubbly personality bordering on braindead, a fondness for money, and a fiercely independent nature. Unassuming and somewhat dimwitted upon first impression, both characters are actually highly competent and confident in their abilities. Most importantly, both consistently choose to do the right thing – despite vocal protest – and both are always left in worse financial situations than they were prior to starting off their quest.

The visual similarities between Mail and Lina are obvious at first glance. Besides their shared tendency to make super-deformed-over-exagerated faces, they both have striking red hair, prefer blue and red attire with big shoulder pads, have collars clasped with a jewel, and wear nearly identical headbands; however, Popful Mail’s concept artists couldn’t bring themselves to create a direct 1-to-1 copy, so some compromises were made, such as making Mail’s clothing more revealing and changing her eye color; another notable difference is the characters’ vocations: Mail is more physically oriented, similar to a fighter class in traditional role-playing game terms, while Lina is a powerful mage more likely to throw a fireball than swing a sword.

*Lina Inverse and Popful Mail; it’s up to the reader to figure out which is which

*Lina Inverse and Popful Mail; it’s up to the reader to figure out which is which

Being a fighter, Popful Mail is the fastest playable character and gains access to swords, throwing daggers, boomerangs, and even a blade-beam that Link would be jealous of. While she may not be the strongest character, she is the most well-rounded and, due to her agile nature, feels fluid and responsive to control, making her the preferred pick when facing dangerous opponents. On top of this, her in-game sprite looks great, with her instantly iconic heart-shaped breastplate.

The two remaining playable characters are less interesting but have their own charms. The first is the apprentice magician, Tatto, adorned in a long red cape and floppy hat. Although slightly slower than Mail, he makes up for it with his proficiency in ranged attacks; wielding various staves with magical properties, ranging from piercing fire bolts to homing balls of light. Tatto, or Tatt for short, serves as a foil to Mail as he possesses a more measured and thoughtful approach to conflict, whereas Mail tends to rush into danger without a second thought if the money is right.

The final playable character is Gaw, a blue-blob-dragon-thing with wings. As his simple onomatopoeia may imply, Gaw embodies the tropeful personality of a dumb but good-hearted barbarian. Unlocked late in the game, Gaw quickly becomes the only character worth playing. In a single stroke of poor game balancing, Gaw has the ability to jump ridiculously high and possesses the strongest attacks among the entire cast. He has access to a powerful flamethrower and later gains a full-screen beam that decimates enemies unlucky enough to be caught in its path, making him the de facto boss killer. Gaw’s only drawback is his slow movement speed; however, his advantages far outweigh his disadvantages. And while he’s a funny looking character with a cool beam, he doesn’t feel as fluid as Mail and manages to become boring to play; which is a shame, because not using Gaw is like purposely cutting off your own legs: dumb.

*all three heroes in their spritely glory

*all three heroes in their spritely glory

There are a number of supporting goobers you meet throughout the game, including an elf named Slick who, despite being well-intentioned, ends up causing more than a few ancient horrors to awaken from their slumber due to his obsession with blowing things up; Glug, a clean-shaven dwarf and master crafter who rebels against the old-dwarven-ways by shaving his face; King Lipps, ruler penguin of Chilly with a pronounced lisp, would likely be played by Patton Oswalt if Popful Mail were ever adapted into a live-action movie. Silliness abound; each of these characters share one thing in common: they’re goobers. They goobify the plot to goobtastic levels of gooberism that only a goober wouldn’t appreciate.

And, of course, no computer game is complete without a rogues’ gallery of dangerous villains. In Popful Mail’s case: a troupe of dimwits and idiots; ranging from hideous to bishōnen, nonsensical to practical. Each villain possesses their own little quirk, and it turns out that the stereotypically “cool” villains are the least interesting ones. The first villain we encounter is Nuts Cracker, Mail’s bounty target, who is a wooden puppet man with a detachable head. We discover that he is working for Muttonhead, an old bald wizard whose primary goal is to resurrect some ancient Overlord (or something). We then discover that Muttonhead is actually working for a seemingly-Swedish muscleman named Sven T. Uncommon, whom you fight in various forms throughout the game. Before each fight, he yells, “Listen to me now and believe me later,” and then proceeds to insult you by calling you a baby in sixteen different ways. He finishes it off with a “Prepare to be pummeled by my manly pumpitude.” Goobers galore.

Like any good Japanese computer game, the serious final villains are the coolest-looking, and it’s no different in Popful Mail. Kayzr, the white-haired wizard of many-a-fictional-anime-girl’s dreams, is a textbook bishōnen, adorned in a flowing cloak and always mysteriously vanishing in and out of scenes, commanding a small harem of women, notably Wriph and Wraph, beautiful elemental twins of fire and ice. Kayzr is the real mastermind behind the scenes, pulling the strings to get the mysterious Overlord resurrected for reasons. The trade-off here is that, much like real life, the more flashy and beautiful someone appears, the more vacuous and braindead they actually are – the qualities are directly proportional with very little exception; and it’s no different here. Kayzr and his gorgeous goons have the least amount of screentime and end up being pushover boss fights; and, in a game full of goofball characters, Kayzr and his groupies end up feeling out of place with no silly quirks of their own. But hey, they look nice, and that’s worth something.

Popful Mail’s gaggle of goobers galore is fairly diverse. Each character could easily slide their way into a ’90s afternoon anime, with many of the villains feeling like perfect filler-episode fodder; and although they may be extremely stupid, these characters play a vital role in elevating this computer game beyond simply another side-scrolling platformer that takes itself too seriously where you hit stuff and do the jumps. The humorous and bickering banter between the numerous conflicting goobers is constantly entertaining, adding a touch of levity to the sometimes frustrating and tedious platforming elements. It serves as a reminder to the player that, as Carl says, none of this really matters; sit back, take a breath, and relax.

*goobers galore

*goobers galore

If you’ve read this far you already know the gist of the story. Some bad dudes are trying to summon an ancient evil named the Overlord. Popul Mail is a bounty hunter who gets mixed up in the plot during her bounty-hunting for Muttonhead, who’s in league with the strongman Sven T. Uncommon and the bishy Kazyr. Mail encounters a gaggle of goobers along the way, some of which join Mail on her quest to save the world.

And, of course, Mail does save the world – is anyone surprised? It’s all very rudimentary stuff; so let’s talk about how she saves the world: let’s talk about the gameplay now.

III, TALKING ABOUT THE GAMEPLAY NOW or: Game Over

Popful Mail is a platformer that includes several elements one might associate with the role-playing genre, such as equipment, items, shops, money to spend at those shops, a party of sorts, health points, stats, and that’s about it. Popful Mail is not a role-playing game (I swear), and these so-called “role-playing game elements” are found in multiple games throughout the decades that are not role-playing games. Grand Theft Auto has shops, Metal Gear has equipment, Castlevania has items, almost every game has health points these days. We don’t consider those games role-playing games, maybe partially inspired by ideas first popularized by games like Ultima and Wizardry, but they are certainly not Ultima or Wizardry or anything remotely similar.

Then, what is a role-playing game? In my expert opinion – I actually have no qualifications whatsoever – a role-playing game is a computer game inspired by Dungeons & Dragons; incorporating a cast of characters, preferably player-created but not absolute, and a level-based progression system that includes a hint of customization. A role-playing game features loot from multiple sources and combat governed by elements of dice-like-chance. Role-playing games embody a sense of “grand adventure,” where active exploration of the world is essential to uncover its secrets; a role-playing game does not simply plop you from one level to the next with clear objectives; and while not entirely necessary, meaningful player choices that impact the overall narrative help solidify a computer game’s status as a true role-playing game. Of course, there are always exceptions to the rule; and many exceptions exist; however, Popful Mail is not one of those exceptions.

None of these distinctions are important. More pedantic than profound, people pother plenty over genre labels in every form of media; bickering endlessly on forums; but ultimately, “none of this matters.” Labels are useful for one thing only, informing people unfamiliar with a thing of what to expect from a thing.

A chair is something with four legs that you sit on, but sometimes a chair has two legs, and sometimes a chair has one leg; dogs have four legs, and you can sit on a big dog provided they’re cool with it – so, are big dogs chairs too? Is a big rock a chair? Is a table a chair?

Who cares – when you see something that is a chair, you just know: that’s a chair; when you play a role-playing game, you just know: that’s a role-playing game.

Whatever labels you choose to use, my motto remains the same: if a computer game looks cool, play it. And indeed, Popful Mail looks cool, so I played it.

*the various shopkeepers you will encounter on your popful journey

*the various shopkeepers you will encounter on your popful journey

The irony of proclaiming genres as mostly meaningless yet describing Popful Mail as a “platformer” is not lost on me. So let me explain. Popful Mail features multiple levels consisting of various areas that require precise jumping from platform to platform. These levels also include dangerous traps such as fire pits, spinning spiky balls, disappearing ledges, and various enemies that need to be defeated to progress – many of these enemies can be skipped by simply jumping over them, a common platformer characteristic.

Popful Mail differs from other platformers of its decade in a few ways, aside from its role-playing elements. The most noticeable difference is the absence of death pits, which are pits that immediately cause death upon falling into them. These death pits, often the bane of players in games like Mario or Sonic, are notably missing in Popful Mail. Instead, the game focuses on incorporating more verticality into its level design and ruining your day when you fall from a tall height.

This verticality is evident right from the first level, a forest zone featuring numerous ladders and tree branches that you must climb to progress. In these zones, falling doesn’t result in instant death but rather prompts a pseudo-redo. It’s like a death sentence in every aspect except actual death, as you are required to retread your steps and jumps to the point where you fell; and since all the monsters respawn, it’s déjà vu.

This game design choice was intentional, evidenced by the lack of fall damage. Instead, when your character falls from a great height, they exhibit an expression as if they’ve taken damage, but in reality, they haven’t; they’ve only come to the realization that they need to re-climb the entire level.

*it’s a platformer, I swear

*it’s a platformer, I swear

Each of Popful Mail’s levels are based on the particular overworld zone you happen to be in. For example, Chilly levels are blue icy tundras and icicle undergrounds; mountain levels are stony-brown caves and mine shafts. Each zone contains similar monsters throughout its levels; the forest zone contains tanuki slashers, midget magicians, and hanging spiders that swing back and forth from treetops; while the mountain zone contains orc miners, bat beamers and silverfish digglers. The enemy variety is impressive, and each enemy has its own gimmick that you must learn and adapt to, like any true platformer.

The controls in Popful Mail are straightforward. As a side-scroller, holding forward moves the character forward, while holding back moves them forward in the opposite direction. Pressing A makes the character jump, and pressing B makes the character attack. These are the extent of the controls. Victory is dependent on how precise your movement is and how well you time your attacks. That’s all there is to it. Popful Mail is undoubtedly a skill-based computer game, one that can be completed without taking any damage and without purchasing new equipment; although, going for the latter option would significantly increase the time needed to defeat enemies, especially bosses.

Combat is simple. Each of the three characters has five weapons, each becoming obsolete once upgrading to the next weapon, with the final weapon – the Aura class weapons – being the strongest, naturally. All attacks have a stun-locking nature to them, meaning if your attacks are timed correctly, a monster can be locked into their recovery animation permanently, thereby preventing their movement and attacks. This tactic is often very useful, unless there are multiple monsters on the screen that you need to pay attention to. And while this is incredibly useful for dealing with threats, it comes across as lazy game design that facilitates boring enemy interactions such as: stand in front of enemy and press A precisely every seventh of a second.

A useful rule of thumb when trying to determine a game’s genre is that if grinding makes progression easier, then you’re likely playing a role-playing game or something very similar. Grinding is technically possible in Popful Mail, killing an enemy over and over for money, but that money can only be used on healing items from shops. No amount of healing items is going to compensate for a lack of skill; and you will definitely need some semblance of skill as enemies do a lot of damage in Popful Mail, especially bosses that send you to the game over screen in two or three hits.

The game over screen becomes your ever faithful companion in Popful Mail, a computer game that seems simple but ends up being extremely frustrating. Your character rides the edge of the screen, making enemies and hazards feel as if they’re materializing in front of you without any time to react. This makes getting hit by seemingly avoidable attacks or hazards a frequent occurrence – a common criticism levied at Sonic games where Sonic’s speed often leads to this same situation. This makes Popful Mail less of a “react to oncoming traffic” experience and more of a “get t-boned by a drunk driver with his headlights off in the middle of the night” type of experience, which can often make Popful Mail feel tedious and unfair to play; especially when some enemies, notably mages, can fire spells at you from off-screen, and do so frequently.

*all three game over screens; something you’ll be seeing a lot

*all three game over screens; something you’ll be seeing a lot

Once the developers assume you have mastered the controls, they serve up the ice zone: Chilly. Every stage is covered in thick icy snow that causes our heroes to slide ever so slightly when walking and leads to uncapped acceleration when holding forward; almost as if every floor tile is a speed-up pad from Sonic, throwing a wrench into how you’re used to playing. Blast processing? It’s here, often blast processing you right into an enemy and straight to the game over screen.

Item shops in Chilly stock “Ice boots” designed to stop the slippage; but woe is me: they’re consumable and break after so many uses, making them nice but dumb and expensive to maintain. While the need for computer games to change things up is ever-present, this change in movement is more frustrating than fun; so despite the aesthetically pleasing Chilly zone, all borealis and blue: no thanks.

Touched on earlier, the world of Popful Mail includes a number of inhabitants, and a few of them have chores for you. Some of these chores are optional, while others are required for progression, necessitating backtracking to previous zones. Luckily, backtracking occurs only a few times; lucky because Popful Mail isn’t designed with backtracking in mind. There is no fast travel system in place, so you must traverse most of the level again to complete these sidequests and then double back once more to leave the zone and return to the NPC in question to deliver the goods. This often requires more platforming through levels already completed because the majority of these NPCs are located in towns maliciously placed in the middle of levels; the solution to this problem is obvious: don’t place towns in the middle of dangerous levels that require a bunch of platforming. Instead, make towns their own node on the world map – but hey, what do I know?

These poorly placed towns are where you’ll end up spending all of your hard-earned money. In Popful Mail, keeping with the bounty hunting theme, money effectively replaces experience points by serving as the only means to enhance your character’s attributes. While there are various consumable items available for purchase, such as healing food and an expensive invincibility amulet, the true value of money lies in acquiring new equipment.

Each character possesses a unique set of equipment: three pieces of armor and a weapon; weapons being the most important, as they offer significant upgrades in terms of damage output; of course, you could stick with the vanilla equipment throughout the game instead but this would be a self-imposed hard mode primarily because you would do pitiful damage to the bosses.

*Mail’s inventory screen; showcasing her armor, weapons and items

*Mail’s inventory screen; showcasing her armor, weapons and items

Before we move on to the bosses, let’s talk about the save system. In Popful Mail, you’re allowed to save anywhere at (almost) any time; and unlike some computer games discussed on this site, you can’t doom yourself by saving in the wrong place at the wrong time. The few instances where saving should be restricted are indeed prevented by the game, indicating that the developers were keen on avoiding soft-locking caused by a poorly designed save system; the ouroboros has been thwarted. However, you can forget to save, then die, and subsequently lose an hour of progress, something that happened to me a lot; with no checkpoint system, the great power to save anywhere comes with great responsibility.

Despite there being three save slots available, it’s possible to find yourself in a pseudo-stuck situation by saving when your characters have low health in the middle of a level. This is often followed by the realization that you have to make it through the entire level without getting hit, and depending on the type of player you are: this is either a harrowing game-ender or an exhilarating “get good” moment; but it is not a soft-lock, more like a will-lock – will you persevere or will you give up?

For instance, after completing the first zone, Treesun, and defeating the first official boss, the Wood Golem, I ventured into the Wind Cave level but saved about halfway through with only 5 HP remaining, meaning one hit would result in a game over; and with no easy means of healing, my path was clear: quit or backtrack to the first town to heal up. The latter required near-perfect platforming through almost two full levels. This backtracking journey ended up taking over 20 save reloads, navigating through both Wind Cave and Treesun with only 5 HP, dying repeatedly. I could have given up, and at a few points, I wanted to, but I kept on; getting better with each death until eventually, I made it through. Is this impressive? Not really. Am I a better person for doing this? Absolutely not. But it did feel good once it was over.

A “save anywhere” system makes situations like the one outlined above more reasonable, as once you hit a milestone, you can save and reload from that spot at any time; however, it also facilitates lazy gameplay, such as immediately reloading upon a failed jump or any slight annoyance whatsoever, which is something I admit to doing once or twice or a lot; it’s a hard temptation to resist: fall from a great height and don’t want to reclimb the level? Reload. Get hit by an enemy? Reload. A built-in savestate system.

This irresistible urge to reload comes into play most often when fighting bosses, which are prevalent throughout Popful Mail and a highlight of the game. These bosses range from push-over to extremely annoying with very little in between. Much like Mega Man, bosses are all pattern-based-games, and without foreknowledge, you’re going to die the first time and probably the second time and the third time as well; or you could just reload the first time you get hit so you don’t have to sit through the game over and continue screens. Bosses don’t fool around when it comes to damage, which emphasizes the pattern recognition aspect of their design.

*bosses, bosses, bosses!

*bosses, bosses, bosses!

Some bosses play fair, with lasers, fireballs, and punches that come out after a tell; all you need to do is pay attention. Other bosses are very intimidating, sometimes feeling impossible to defeat – until you stumble upon a gimmick to kill them. A perfect example of this is the first boss, the Wood Golem, whose rocket punch attacks are hard to dodge, and if you get too close, he rushes back and forth quickly in an almost unavoidable manner. I reloaded several times on this boss before realizing that if I get behind him, it forces him to do his backwards rush attack resembling a butt-bounce, and if I attack him during this, it puts him in a recovery animation. By timing attacks properly, I can stun-lock him in this recovery animation, making the fight go from dying repeatedly to defeating him without taking damage; which feels a little weird?

This stun-locking tactic comes into play a lot, especially with mooks, but also with a select few early-game bosses where this clearly shouldn’t be the case, as it feels like lazy game design; a poor solution to boss fights. Later bosses such as Kayzr, Wriph, and Wraph avoid this by vanishing or moving quickly after being hit, but these bosses are easy in their own way, as by that point, you have Gaw and his full-screen laser. A few bosses feel unfair, such as the Fire Golem, who launches fireballs out in a haphazardly random manner, making damage unavoidable – a frustrating exercise in repeated reloads.

Popful Mail’s bosses, all imaginative and goofy in its signature style, are a highlight; however, while occasionally frustrating, they are often underwhelming in terms of difficulty, with the difficulty curve being unusually frontloaded, and that’s not because of simply getting better at the game. The last three bosses of the game, for example, fall into this category, which is disappointing when one is conditioned by Mega Man and Castlevania to expect final bosses that require a high level of tell-reading, prediction, and near-perfect execution. The penultimate boss has one attack: a homing ball of energy; the final boss has two: a rocket punch and an energy ball, both of which are easily jumped.

But it’s not all boredom. There are a number of bosses that evoke the timeless satisfaction of slowly getting better through repeated failure, a feeling any platformer aficionado is familiar with; this feeling is just few and far between, with frustration and malaise filling the void between these fleeting moments.

IV, THE END or: Computer Games Are Very Serious, Aren’t They?

Popful Mail is a platformer; but really, it’s its own thing. The role-playing elements combined with the progression systems make it resemble Super Metroid in some ways and classic Castlevania in others; close to a “Metroidvania.” However, there is not enough gameplay variety or interesting backtracking to truly make that comparison.

In other ways, Popful Mail feels like Super Mario, especially with all the jumping and its world map progression; but the actual combat resembles the later Ys games, which makes sense as the original developer, Nihon Falcom, made both series. As with both series, the few actions you can do, jumping and attacking, feel great in all respects.

Ultimately, Popful Mail is a linear adventure in a world of swords and sorcery. The only meaningful backtracking involves retrieving chests that were previously out of reach before unlocking Gaw or talking to someone in an earlier level to obtain an item necessary for progression in a later level. There are no true movement upgrades, which causes the gameplay, while responsive and satisfying, to feel stale after the first few hours. Although new characters and weapons add some variety, they do not significantly alter the way the game is played. As a result, you find yourself repeatedly performing the same actions: jumping and attacking. One could argue that this is an unfair and reductive perspective but it could always be further reduced to simply “all you do is press A and B.” The point being, the inclusion of abilities like double jumps, hovering, or dashing would have kept the gameplay interesting.

Popful Mail’s role-playing elements are superficial; for a game that tries to lean into its role-playing tropes, it misses several low-hanging fruit. For example, equipment is always purchased from shops, with the exception of ultimate weapons, which are simply given to you near the end of the game. It would have been more engaging if Popful Mail required some form of light questing to forge these final weapons or acquired some from chests hidden throughout the world. Another example: there’s an attributes screen with various stats listed, but I couldn’t tell you what they are because it’s entirely pointless to look at, as the next tier of equipment increases your stats without exception. You’d think the Flame Robe would ward off fire damage, but no, it only increases your defense a little bit. The only true attribute that matters is money. Money and equipment function as experience points and leveling up, respectively, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but it’s half-baked and linear, with every upgrade feeling samey by not adding any significant gameplay alterations.

Popful Mail misses every opportunity to be a good Castelvania game. Good thing it’s not a Castlevania game. And, although released before “Metroidvania” even became a word that people use, Popful Mail would have benefited from borrowing elements from the Metroidvania format, because it already comes incredibly close to begin with; considering time travel is seemingly impossible, I suppose it is unfair to criticize a computer game for not being like future computer games, but the feeling that something is missing is hard to shake.

*end game credits

*end game credits

The overall presentation is good, though. The graphics, powered by the Sega CD add-on, are colorful and poppy, fitting the goofy nature of the game. Every sprite is incredibly detailed, with enemies and bosses that feel like they jumped out of a ’90s anime. The cutscenes are beautifully drawn and add to the classic anime aesthetic that Popful Mail embodies so well.

The music, unfortunately, does not fare as well. Quintessentially Sega Genesis soundchipped, with chunky bass and grainy drum cracks, yet the tracks themselves are not melodically interesting enough to warrant listening to for hours on end. Every track plays at a high BPM in a short loop, sounding like a mixture between house and ’90s electronic – think Alice Deejay’s “Better Off Alone” but more cheery and less catchy.

Each of the five zones contains a unique track that plays continuously throughout, with one or two exceptions during the final stages of the game and when entering shops. The monotonous music, more suited to adventuring, even plays when you enter a town – a transition that one would hope to be accompanied by more relaxing music.

The lack of musical transition between platforming and towns further emphasizes the true focus of the game; the role-playing game that’s not a role-playing game. You have to keep moving; there’s no time to relax. Turning the game into a Sonic title, as was originally intended, makes sense in this regard. The towns full of non-playable characters are an afterthought. All jump and slash. There is no chill; only 168 beats per minute.

There are two types of computer gamers: one that is endlessly frustrated by the tedium of repetition, and one that feels an immense sense of satisfaction from getting better by repeatedly failing. Both end up turning the game off to cool down for a moment; both may lay in bed at night, close their eyes, and visualize playing the game perfectly. Then, upon getting that second wind, turning the game back on with this newfound confidence, only to immediately die again – the first player may move on to another game at that point; the second would continue forevermore until mastery.

Popful Mail, like many platformers, will teach you a lot about yourself. After all, computer games are very serious, aren’t they? Do you have the patience to overcome the frustration, or will you put the controller down and stop playing? Is one better than the other?

Maybe having the patience to overcome Popful Mail is indicative of how patient you will be with other hardships in life; or maybe giving up is indicative of a wise person who sees no true value in investing time in a computer game that is more frustrating than fulfilling, rather spending that time on something more important or enjoyable. What does one truly gain from completing a computer game anyways? Bragging rights – is that it?

Popful Mail, very much so, personifies these questions, and in this way, Popful Mail succeeds as a computer game.

Of course, you know my position: if you get bored, do something else.

(Originally published on 6/25/2023)