Kill All Monsters

I, INTRODUCTION or: Abuse Awakens

High above the clouds, a great tree pierces the heavens like the mythological Yggdrasil, with branches resembling legendary dragon-slaying halberds impaling the clouds, and thick dew-encrusted leaves falling from such great heights that they disintegrate before touching the ground. This is a world full of sprawling hollows, teeming with humans and monsters alike; bazaars perched on gigantic leafy bird nests repurposed into bustling plazas, and children running about freely. Fertility and happiness flow in abundance – but only for humans.

In this world, monsters both live among the humans and are hunted, captured, forced to breed, and treated like less-than-nothings; their meat thrown around so haphazardly one has to wonder where it all comes from. This is a world in which “Monster Masters” collect and battle monsters in bloodsport against other “Monster Masters” just for the sake of it; pitting creature against creature in a manner not dissimilar from dog fighting. Only, unlike dogs, these creatures can talk; they can vocalize their pain in human tongue.

This is the world of GreatTree; a world separate from our own by virtue of computer-games but equal in essence-and-quantity-of-suffering.

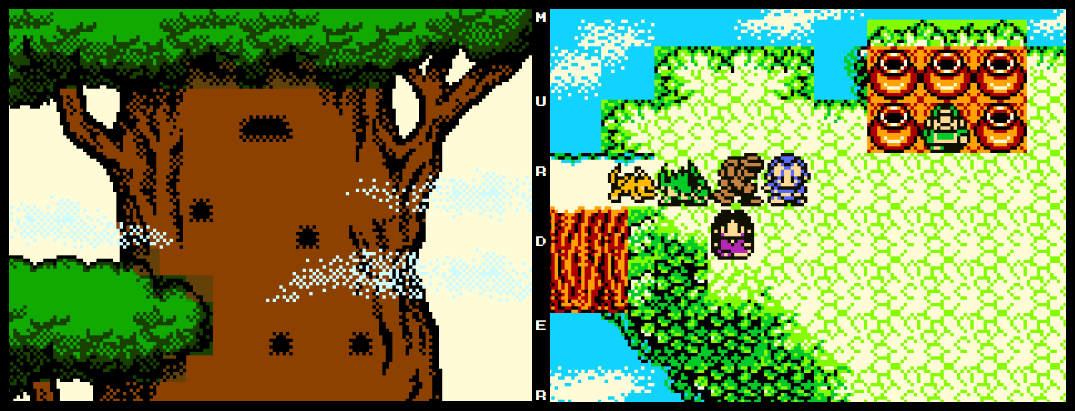

*Beautiful GreatTree; pictured Terry, a Monster Master, strolling through the leafy bazaar on a bright sunny afternoon.

*Beautiful GreatTree; pictured Terry, a Monster Master, strolling through the leafy bazaar on a bright sunny afternoon.

GreatTree is a world conjured into existence in 1998 by the electrical synapses snapping about inside Yuji Horii’s brain; fellow Earthling and homo sapien too: the creator of the computer game series known as Dragon Quest or, at the time in North America: Dragon Warrior. So enamored was Yuji Horii with the prospect of simulating creature collection, captivity, and castigation; inspired by the seemingly infinite cash-money-machine of Pokemon two years earlier – a series also known for pitting creatures against each other for bloodsport – he had to create his own version: Pokemon Dragon Quest Edition.

Yuji Horri drew on his existing Dragon Quest series to capitalize on the budding creature-collecting-phenomenon for his parent company and overlords: Enix. Reusing Akira Toriyama’s enchanting monster designs – now mythical Japanese iconography – and setting the narrative within the existing Dragon Quest VI universe, to create a spellbinding world already familiar to any Japanese computer gamer who knew the first thing about electronic games.

Adding to the charm is the return of jingle-smith Koichi Sugiyama, main-composer of the Dragon Quest series and, less known, politician of questionable ethics; Sugiyama composed seven new songs, pulling the rest – primarily overworld and battle themes – from previous Dragon Quest games, primarily Dragon Quest VI. Each of these new songs capture the childlike wonder of the GreatTree wander; upbeat and pleasing in hopes one overlooks the virtual violence, both mental and physical, acted out by the beautiful, bright, and bubbly sprites on screen.

Dragon Quest (Warrior) Monsters is a clear attempt at turning Dragon Quest into Pokemon; and while this might seem socialist-cynical, I assure you: it’s not – this transparent capitalistic endeavor – true of all computer games – produced an excellent handheld Game Boy title rivaling its primary competitor, even on its worst day, complete with its own link-cable functionality for battling and trading with other real-life homo-sapiens; no feature lost in the inspiration translation.

Competition can be a good thing, sometimes.

And competition is all that matters in GreatTree, one of many trees composing a great forest of gigantic cumulus-culling trees, including but not limited to: GreatLog, BigTrunk, and DeadTree. Each tree has its own “Monster Master” representative, and each year a monster battling tournament is held, the Starry Night Tournament, where creatures are pitted against each other in brutal bloodsport to determine which tree has the most powerful Monster Master; and as added incentive, the winner has any wish they desire come true.

Instead of masters fighting in old-fashioned combat, they rely on tamed and cyclically inbred creatures to do it for them. Cowardice and shame are not part of the GreatTree vocabulary.

Terry, our hero, and later famed anti-hero of Dragon Quest VI – possibly due to his experiences here – is the chosen representative of GreatTree; a silver-haired youth donned in a blue tunic and something akin to a beanie of matching light-reflection.

Terry’s just a kid, and one day upon waking up in the middle of the night, his sister – Milly – is kidnapped; searching throughout his home and finding no trace of her, Terry eventually stumbles upon an odd portal in a living-room cabinet, and just like that, he’s transported to GreatTree and accosted by its guardian, Watabou, a monster of the fluffy-white-and-wooly variety.

*Terry watching over his sleeping-sister, Millayou; presented within the Super Game Boy frame depicting Watabou in the bottom left and Terry on the right.

*Terry watching over his sleeping-sister, Millayou; presented within the Super Game Boy frame depicting Watabou in the bottom left and Terry on the right.

Watabou gives Terry an ultimatum: become GreatTree’s Monster Master and win the Starry Night Tournament or return home and lose his sister forever. Terry’s path is obvious; after all, the best choices are pantomime, and Terry picks the only choice available to him: abuse, violate, and kill all monsters.

Terry’s journey to find his sister is fraught with death and psychedelia. While GreatTree is a beautiful homebase full of monster farms, breeding grounds, and residential hollows; the actual adventuring happens outside the tree. Within the basement of King GreatTree’s quarters lies many doors and behind these many doors lies many portals, each of these many portals transports its user to one of many overworlds teeming with its own variety of creatures. These portal worlds are controlled by a primary boss monster, which, in every case, simply wants to be left alone.

But Terry will never find his sister if he leaves these creatures alone. He must travel through each portal slaughtering all creatures in his path, and in some cases tricking them into joining his cause. Countless mini-genocides left behind like snail’s slime; and, instead of Terry’s sword slicing through goo that stains his blade blue, monsters do the dirty work for him; violence by proxy. The Monster Master becomes the monster.

And like the signature Dragon Quest Slime, we – the player – ignore the abuse and keep smiling.

In true homo-sapien fashion: we turn a blind eye.

II, GAMEPLAY or: Methods of Violence

The ultimate lifeform; this is what all Monster Masters seek: a creature that knows all the right skills and possesses all the right attributes, with a docile disposition so as to be content with its brutal lot in life – constant violence and painful death. Terry’s journey to win the Starry Night Tournament is intrinsically linked to this pursuit of escalating violence; like the farmer selectively breeding chickens with the largest pectoral muscles – that succulent white breast meat so thoroughly craved by the drooling populace – each Monster Master has their own selectively bred creature to tear through their opposition’s flesh.

The Starry Night Tournament is a perpetual contest of strength; not physical or mental strength, but oppressive and abusive strength. With different tiers Monster Masters must climb to prove their worth.

Terry ascends the leaderboards by climbing a pile of monster corpses.

Early in Terry’s journey, he is gifted a smiling blue slime – iconic mascot of the Dragon Quest series – named “Slib” by default, a creature belonging to the eponymously named “Slime” family consisting of countless smiling slimes of all colors and conditions. Slib comes with an “Easy Going” personality, making him the perfect victim – endowed with just enough bravery to weather the hardships of battle all while keeping a cool head; like any successful middle-manager, Slib is the starting point for Terry’s liquidation of all things.

And while every Slime comes with a unique personality, Slib is truly special because he’s the first of the gang to die. No one told Slib about his role in Terry’s quest. A lamb ignorant to the slaughter.

Using Slib as a starter, Terry battles through portals leading to other worlds; large open worlds full of green-grass-gradation and white-water-waves. Familiar musical themes jingle in dichotomous harmony as Terry ventures through these worlds with three monsters in lockstep behind him cutting down anything that crosses his path.

Each world comes with its own flavor of randomly generated length, scenery, treasure, and occasional floor puzzle. And as Terry’s adventure continues, these worlds become progressively more complex, with maps resembling a pig’s nervous system laid bare after being flayed alive and tilesets mirroring that of dungeons, deserts, fiery hellscapes, or simple forests; the variety and eventual complexity akin to the twisting assembly-line-of-torment a chicken might travel before getting its wings clipped and head cut off.

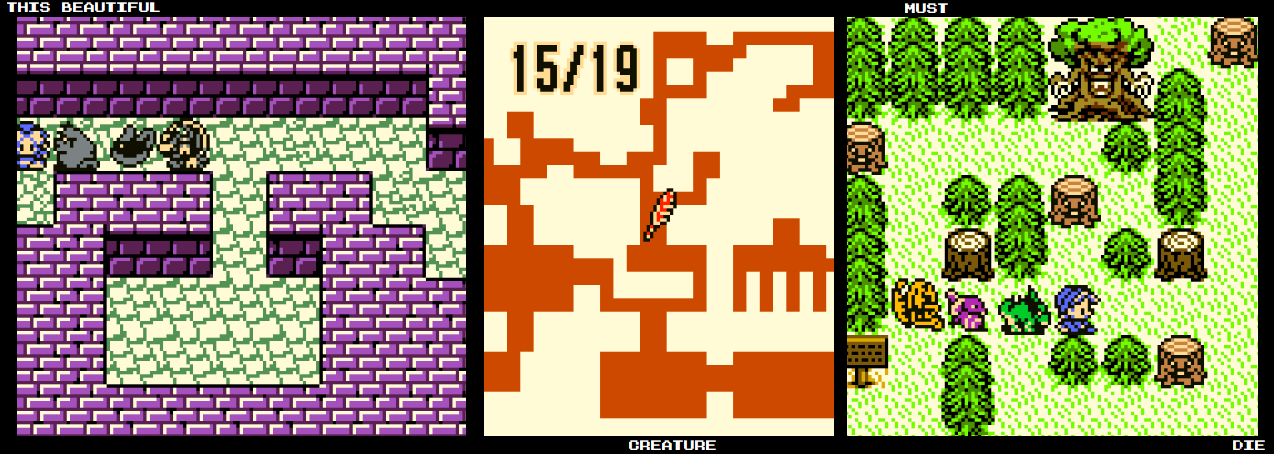

*Sampling of tilesets, including a map resembling a nervous system laid bare.

*Sampling of tilesets, including a map resembling a nervous system laid bare.

Each world consists of several floors interconnected by portals. Many of these portals are straightforward, taking Terry to the next randomly generated floor; others are less linear, teleporting Terry to a coliseum, casino, church, or item shop. Much like the Mystery Dungeon series, random occurrences are a key feature – not a bug.

The randomness of it all – like a tanuki playing tricks inside the mystery dungeon – is something I’ve come to appreciate in my middle-age; predictability perishing from the psyche, forcing reliance on pure perspicacity; and from the player’s perspective, it’s a lot of fun – the violent unpredictability of never knowing what’s next.

For Terry to truly conquer a world – “beat” the level – he must overcome a challenge on the final floor. This is typically a boss monster, quite often non-violent and simply wanting to be left alone.

In one instance, Terry comes across a large green dragon surrounded by her near-ready-to-hatch eggs. Terry talks to the dragon, but she’s content, no troubles in the world. Terry is stuck; with no true opponent, what is he to do to complete this world? Luckily, the adventure has conditioned him thus far into making the obvious choice: start messing with the eggs and kill the whelps that come out.

Once enough whelps are slaughtered, the mom grows angry and attacks, giving Terry the perfect excuse to kill her as well. Once Terry’s monsters are done feasting on the mother’s corpse, Watabou comes out and congratulates Terry on his victory, teleporting him back to GreatTree. All in a day’s work for a seasoned Monster Master.

Another telling example early in Terry’s adventure: tasked with traveling through a world in search of a missing Heal Slime. After countless floors, Terry finally comes face to face with the creature – a blue jellyfish-like being with a signature bright slime smile. The Heal Slime, whom Terry learns is named Hale, explains that he ran away from the monster farm because life there was frightening, and he yearned for freedom. He pleads to be left alone, as all he desires is a peaceful existence.

But that’s not acceptable.

Terry readies his monsters and launches an assault against Hale, forcing the little blue jellyfish slime into submission. Hale, beaten-battered-bruised, and cowering for his life, musters the strength to get up and, with his final breath, humbly requests to join Terry’s party. Terry, in his childlike-whimsy, happily agrees but immediately sends Hale back to the farm – the very place Hale had wanted to escape to begin with.

Hale will make for good breeding fodder in pursuit of the ultimate lifeform.

*Dragon Mom protecting her eggs while Hale the Heal Slime hides from Monster Masters in a cave.

*Dragon Mom protecting her eggs while Hale the Heal Slime hides from Monster Masters in a cave.

Hale, like many creatures before and after him, has been tamed. Not all creatures are as simple to tame as Hale, but all of them need to be coerced through the same method: violence. Meat items can be fed to wild creatures as an additional incentive for them to become docile, but the underlying mechanism remains: violence. Feed them meat, then hit them. Keep hitting them until they join you or die. Meat is a key item found throughout the realm of GreatTree, often littering the various portal-floors in the shape of rare steak with bones protruding from each end.

Succulent meat is not only irresistible to human creatures but also to monster creatures who crave it: ribs, sirloin, beef jerky, and pork chops are all common delicacies in the land of big trees.

Having seen no Earthly creatures among the realm of GreatTree, one can only assume that these meat treats are filleted from the flesh of the very same creatures Terry is feeding them to.

Dr. Hannibal Lecter would be proud to know that little Slime Jr. is eating members of his own species.

Once Terry tames a creature, he can send it back to the farm or replace one of his current monsters with the new meat. With only three party slots available, Terry often sends monsters back to the farm to rot; never personally interacting with them outside of forcing them to breed with other creatures when he chooses, hoping to create a new lifeform stronger than its parents; a new creature to raise through the perpetual violence of grinding wild creatures into a pulp.

This violence is played out in the battle system, which is simplicity personified; following the same turn-based structure popularized by the previous Dragon Quest titles. A monster’s speed attribute determines its turn order, and Monster Masters provide general commands to their enslaved creatures.

While monsters can be commanded directly, such as “use a heal spell,” it is encouraged to use the automatic battling features as the default method of combat, where commands such as “charge,” “cautious,” and “mixed” serve as shortened forms of “attack as you see fit,” “be careful and use defensive skills,” or “do a mixture of both things as the situation dictates,” respectively. In this way, battles are a simple matter of dumping ants into an ant farm and watching how things play out.

This automatic style is encouraged in a few ways: each monster has its own distinct personality that favors specific battle types, and in all important battles – including tournament battles – direct control is turned off entirely in favor of general battle commands. This approach plays into the unique personalities of each monster, as certain creatures will refuse to follow commands they don’t agree with, choosing to ignore them altogether and do their own thing if they so please; further reinforcing the fact that these creatures are not simply mindless monsters, but beings with their own will and desire.

*Battle scene, depicting three monsters; puppet, plant man, and metal slime.

*Battle scene, depicting three monsters; puppet, plant man, and metal slime.

Thanks to the automatic nature of battles, facilitated by the player’s floating finger hitting one button – the action button – the majority of battles are stress-free and relaxing – mindless even – a sharp contrast to what’s happening to the creatures on screen. And, while this might seem like a boring, relatively hands-free experience, it plays into the player’s favor as grinding is an evil as necessary as the captive bolt into a calf’s brain before the meat tenderizing process begins.

All this on top of the fact that Dragon Quest Monsters relies on only three buttons – considering the directional pad as one button – you can play entirely one-handed; slaughtering creatures endlessly with one hand while sizzling your hot dog meat on the burner with the other, or whatever you do in your free time. Abusing animals has never been this easy.

Grinding creatures to a pulp is essential as every creature born from captivity starts at level one; the birds and the bees hard at work but not hard enough to transfer some experience from mom and dad to baby. This leads to a situation in which, after each egg hatches, a session of grinding is needed. The factory farm of experience must continue for us to have nice things, regardless of the suffering caused.

In his never-ending quest for experience, Terry is his own self-sustaining slaughterhouse four.

Provided you have a male and a female monster, you can force any two creatures to breed, producing offspring of varying looks and abilities. Each newborn adopts the abilities of the parents, and depending on the parent’s level and pedigree, the offspring may be an amped-up version of their standard form, indicated by a little plus sign near the monster’s family name.

Once a creature is born, the parents take off, lost forever; perhaps to be encountered during a Monster Master grinding session, killed in the frenzy, or fed the meat of their own species when attempting to re-recruit them in the wild. Regardless, the child is left with no true parents, only Terry, a boy of childlike whimsy and dubious ethics whose only goal is to find his sister; unconcerned with the crying babes of monsters; these creatures used only to further his own goals.

Unlike similar monster collecting games of the era, Dragon Quest Monsters has no tier list. In this game, the tier list is determined by whatever monster you manage to get all the best skills and stats on. There is no true cap to the breeding process outside of the monster family, which is easily manipulated. While this system is unique and freeform in nature, it means there is no true competitive endgame from a real-player perspective.

In contrast, other series, such as Pokemon, have typing and monster match-ups that alter the course of battle; their monsters can only learn a certain selection of attacks, whereas Dragon Quest monsters can learn whatever they want and do whatever they want. This enables a Monster Master to truly make the ultimate lifeform, and have it be – mostly – whatever they want it to be. However, this achievement requires immense effort due to the grind and low success rate of monster taming.

*Breeding process; mom and dad make egg, egg hatches into Poisongon +8.

*Breeding process; mom and dad make egg, egg hatches into Poisongon +8.

But it’s all for a good cause, right?

Terry has to find his sister. And, considering the circumstances he’s been thrust into: killing, hoarding, and forcing other beings to breed seems reasonable. After all, Terry loves his sister.

One human life surely outweighs the countless monster lives lost in Terry’s noble quest, right?

Once Terry achieves true mastery of his murderous craft, he faces off in the final bracket of the Starry Night Tournament. Fighting through a number of experienced Monster Masters, defeating each before going head-to-head with the final contestant.

The final Monster Master in the tournament is his sister – Milly.

We find out that every so often, the denizens of the Big Tree World kidnap “children with potential” from the human realm. These children are then trained to become Monster Masters and coerced into participating in the Starry Night Tournament. Milly, Terry’s sister, was chosen by GreatLog – kidnapped in her sleep; and Terry was a reluctant second choice, as the guardian of GreatTree originally was looking for Milly, but she had already been kidnapped by the guardian of GreatLog; so, the guardian settled on Terry.

Terry’s sister followed the same path as Terry; both looking for the other, both committing small genocides on their quest to find each other.

All to satisfy some sick monster tournament in the clouds.

III, DEATH FOR NO REASON or: Meat is Murder

Human children, babies, infants, and toddlers are helpless. It takes a little over a year for a toddler to take their first steps, and another twelve months to walk properly; upwards of three years to form basic sentences, and five years to become even somewhat self-reliant, capable of basic reasoning and logic. All the while – through this entire process – needing an adult to protect them, feed them, and clean their bottoms regularly.

Even at five years old, a little human has to go through another ten years of life before even thinking about surviving without a guardian to guide them.

Considering these facts, it’s a wonder the human race survived to this point at all.

Kittens can stand on all fours only three weeks after birth, and can survive on their own only twelve weeks after birth, quickly becoming smart enough to get into trouble; only for mama-cat to scruff them by the neck and carry them back to the designated kitten safe zone.

Puppies can survive on their own after eight weeks, with abandoned puppies quickly learning how to scavenge for human food in alleys and suburban trash cans.

Chickens take about six weeks to start living on their own; however, it’s well documented that without companionship – a flock – chickens become depressed and in some cases, suicidal; refusing to eat or drink.

Many calves can be separated from their mothers at four weeks old, or even earlier, in a process known as “weaning” within the factory farm industry. After their calves are taken from them, the mothers bellow and cry for days; their human-like cries compound into a cacophony of suffering, echoing off the metal-plated siding that comprises their poorly ventilated and extremely cramped barns.

*Terry is confronted by the animal avenger; presented with the impact, reality, and consequences of his actions.

*Terry is confronted by the animal avenger; presented with the impact, reality, and consequences of his actions.

95,000 cattle are killed per day. 17,000 chickens are killed every minute; 300 every second, and another 3000 in the time it took this writer to write this sentence.

That’s a lot of succulent meat for the human creatures to feast on.

And meat is not necessary for human survival.

Given this genocidal splendor, perhaps human survival isn’t such a mystery; humans are the craftiest and most intelligent creatures on the planet, after all. Survival of the fittest, and we are the most fit, crushing everything that doesn’t look like us under the weight of our efficient metal tools and automated death machines.

But why do we do this? Why is human life so much more sacred – valuable – than any other life on the planet?

Is it because we value intelligence? If we do, why would we care so much about the mentally handicapped? Were the ancient Romans right for killing the mentally deficient in their own society?

If intelligence is so important, why would we care about the elderly suffering from dementia? All that knowledge lost; perhaps we honor the idea of this lost knowledge?

And why would we care about children? Is it their potential? Do we value the potential of being intelligent, or the potential of having a human experience? If that’s the case, wouldn’t we then have to give in to fundamentalist Christian demands of sex for procreation only, repenting for all intercourse performed under the influence of birth control?

All that spermicide makes angels cry.

Some really smart dead people with bad haircuts, less than skeletons at this point – literally dirt – hypothesized that humans value other humans because they are moral agents; animals are stupid and can’t grasp the concept, so morality doesn’t apply to them, and as such: we can do whatever we want to them. In short, we value the capacity to abide by the social contract; if another creature can follow our predefined social contract – don’t kill, steal, rape, and countless other rules – then we value that creature.

That creature is considered a moral agent; we have determined it can distinguish between the arbitrary concepts known as “right” and “wrong,” and its reward – virtue of the genetic luck of not being born a pig – is being spared a violent death, not being sliced up, and not being eaten.

Fortunately for us, the definitions of morality – and subsequently: the social contract – are created by the very ones who enforce them, and they are only understood by those creators – humans.

We’ve made words and we’ve told creatures who can understand those words to abide by those words; just so happens: only humans can understand the words.

Philosophy is semantics and doesn’t account for the essence of suffering. Pontificate too much and you’ll think yourself into a lobotomy.

*Pantheon of dead philosophers, the more names dropped the more smart you are.

*Pantheon of dead philosophers, the more names dropped the more smart you are.

And we’re no closer to figuring out why human lives are more important than other creatures’ lives.

The simple answer could be biological; we are hardwired to care for and protect our own, but that’s too easy. Like the chameleon’s ability to concentrate pigment granules into camouflage, humans were endowed with the ability to think really hard, so let’s think really hard about this some more.

A true utilitarian would argue that humans value humans for self-preservation, and that society would break down if we didn’t value human life as highly as we do. If murder were acceptable, people would be killing each other a lot more than they do now. This, of course, is not sustainable and leads to bad outcomes very quickly. This can be extrapolated to thievery and any other action that violates bodily autonomy, as normalizing any of this behavior would be, uh, bad – probably.

Non-human creatures don’t recognize or understand these concepts. A wild bear doesn’t care about your bodily autonomy, in the same way a burglar breaking into your home doesn’t care about your bodily autonomy. The only difference is that one is voluntarily breaking the social contract, and the other is just being a bear, ignorant of the human ways – unable to understand the words necessary to abide by the contract.

One can assume that a burglar breaking through your window is a threat to your life, so you would be justified in hitting them over the head with a metal baseball bat; however, the bear is just chilling – perhaps he smelled something good in your trash.

Killing in self-defense could be seen as a morally permissible act, especially if your life is in danger. And while self-defense may be permissible, what about stumbling upon a bear during a camping trip? The bear is scared, annoyed, whatever, and becomes aggressive. Is killing the bear now self-defense, or is this a simple case of human stupidity?

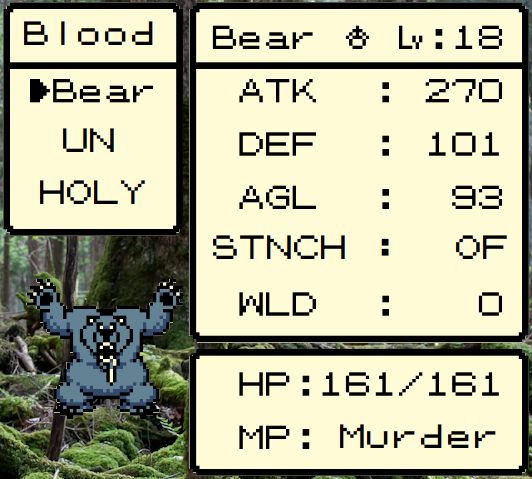

*Monster resembling a grizzly bear; high attack stat, low intelligence.

*Monster resembling a grizzly bear; high attack stat, low intelligence.

In Dragon Quest Monsters, the strong dominate the weak. Monster Masters rule by virtue of strength and cunning over the lesser creatures, manipulating them into servitude until they are forced into captivity and bred into obscurity.

But the roles could be reversed; what if the monsters were more powerful than the humans? All it would take is a single uprising, and the monsters could turn the tables and subjugate the humans; computer game logic – obviously – prevents this, but if translated into real life, the results are clear.

Imagine for a moment an advanced species of alien from the constellation Kasterborous arrives on Earth. They are far more intelligent than humans. They see us as insignificant, as we see other animals, useful only to mine the gold needed to line the wiring in their super-advanced-faster-than-light-super-ships.

Suddenly, the human race is cattle.

This is why the “survival of the fittest” justification fails as a long-term sustainable worldview. This type of violent Darwinism only produces favorable results when you are at the top of the food-chain. The moment an apex predator arrives – a creature stronger or smarter than your own species – you are now the subjugated species; you are now being lined up and forced through the meat grinder; and when you ask them why, they’ll tell you to read a long book by some dead guy with a really weird-sounding name, which basically amounts to “we’re better than you.”

Thank the Gods for that meteor; otherwise, dinosaurs would rule the Earth, and I wouldn’t be writing this Peta advertisement.

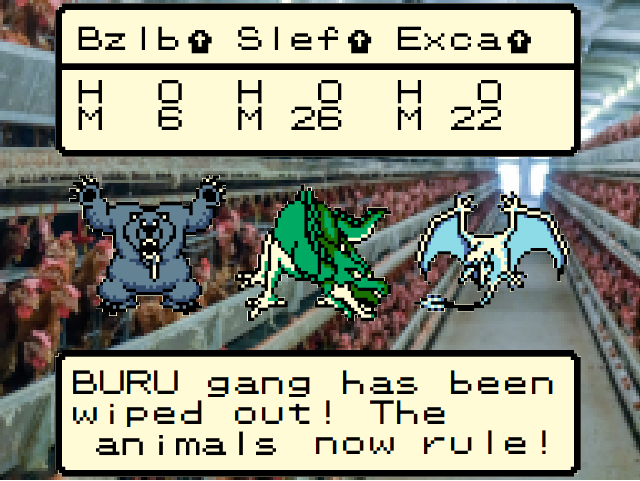

*Animals have revolted; the factory farm liberated; the humans subjugated.

*Animals have revolted; the factory farm liberated; the humans subjugated.

The sad truth is that humans value things that look and act like humans. In most cases, this is other humans; however, attachments can be formed with creatures of all types if they exhibit just enough human-like characteristics to capture the heart of the right human.

Cats know how this works. After assessing a human, they will prance up and nudge their fuzzy heads into the human’s leg – a sweetly-veiled attempt at a long-term goal: survival. If they can make you think they can relate to you on even the most basic level – minor shows of affection – they can survive in their brutal world, maybe even scoring a place in the human’s house if they head-bonk the right person.

Many of us will treat a cat like a queen but turn our heads in feigned ignorance when presented with the horrors of how the twenty-piece chicken McNuggets arrived on our dinner table.

This arbitrary selection of kindness works for cats. It doesn’t work for the creatures this kindness does not apply to; and divvying out kindness in this manner to some and not others goes against everything our second-grade teachers ever told us: “If you bring candy, you should bring candy for the whole class.”

But, some of the kids in class look ugly and I don’t like them.

The pig, a very intelligent animal, is given less human-consideration than a dog; not because we can’t form semi-intelligent connections with pigs – because it’s well documented that we can; it’s because pigs aren’t as cute, they aren’t as expressive, their eyebrows don’t convey a certain range of aesthetic emotion for us to empathize with.

The more expressive a creature’s face, the less likely that creature’s carcass will be hanging from a meat hook next week.

We’re not better than pigs or cows because we can write dumb articles on computer games or do advanced calculus; ultimately, none of that matters. We are biological urges masquerading as autonomy, no different than any other creature. Our enhanced intelligence is a series of evolutionary quirks, no different than the incredible ability for the crow to fly or complete puzzles – our puzzles are just more complex.

And while we may trick ourselves into believing that free will makes us different from other creatures – does the body rule the mind or the mind rule the body? I don’t know. It’s likely that the question is meaningless, as both are products of biology; they’re the same.

Free will is an evolutionary magic trick – a trick we refuse to unveil, as lifting the curtain would be incomprehensible.

In the grand scheme of things, we are no better and no worse than any other animal. What we perceive as “higher choice” comes from instinct, circumstance, reactions to stimuli, a series of antecedent causes.

Even if one does not fully believe in these concepts or have definite answers to the questions, the fact that the questions exist at all should give one pause when considering the treatment of non-human animals.

If there is even a chance that we, as humans, are more similar to non-human animals than we initially thought, more alike than different, then the genocidal justifications start slipping away; perhaps all the excuses, semantics, and philosophical-posturings are simply byproducts of the subconscious-collective-guilt we feel as a species knowing that we brain-bolt, skin, tenderize, and eventually package the meat of cows in tight polyvinyl chloride wrapped over plastic trays at the supermarket – murder on display in neatly organized rows.

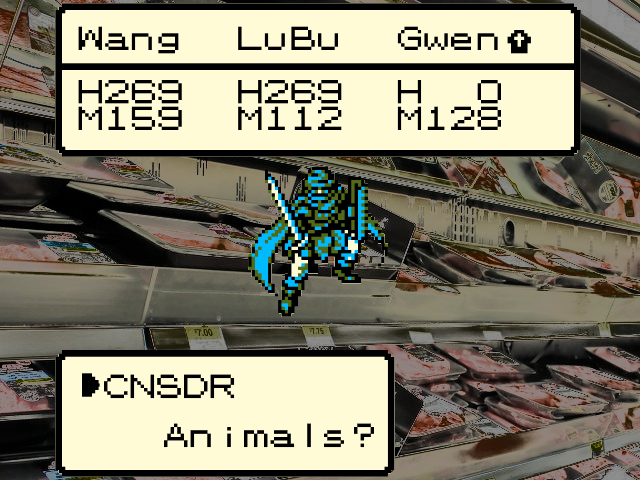

*Terry fights himself; forced to consider what he has become; a murderer.

*Terry fights himself; forced to consider what he has become; a murderer.

Regardless of political views, philosophical leanings, and religious backgrounds, there is one thing we know is true about all animals – including ourselves.

We don’t want to die.

We wake up.

We interpret the world around us.

We feel pain.

And we don’t want to die.

IV, ANYWAYS or: Conclusion

After winning the Starry Night Tournament, Terry wakes up in his bed at home; his sister sleeping on the other side of the room. Everything is back to normal.

Terry wakes his sister and gives her a big hug. His sister explains that she had the “strangest dream”: a dream of monsters, tournaments, and big trees in the clouds. A dream where they both were kidnapped and forced to fight each other. Terry, amazed, says he had the same dream, and they both start to wonder if it was a dream at all.

Terry, feeling something large and slimy in his pocket, pulls out a stick of meat: a pork chop or steak of some kind and stares at it. The euphemism is not lost, and it’s the same type of meat treat he would use to tame monsters in his dream.

The implication is obvious.

Just then, Watabou pops out of a cabinet, drooling, intently focused on the meat treat, proclaiming, “gimme that meat!”

The credits roll.

*... and they lived happily ever after.

*... and they lived happily ever after.

Anyways, Dragon Quest Monsters for the Game Boy Color is a “good” game – whatever that means. Contrary to this entire collection of words, it is a relaxing, wondrous experience that is not at all about animal rights; it’s simply about collecting all the monsters and winning all the battles.

Dragon Quest Monsters is the type of game you swear you played as a kid when your friends couldn’t come outside to play during the summer, even if this didn’t actually happen. It’s the type of game that implants false childhood memories inside your head, creating fictitious déjà vu-like experiences every time you turn the game on.

The monster-collecting aspects, despite being the first in the series, are surprisingly refined and robust. With over 200 monsters to collect – 49 more than the game that inspired it, Pokemon – the breeding mechanics, while adopted from Shin Megami Tensei, are also a refreshingly new experience when coming off of Pokemon Red and Blue – and let’s face it, no one in North America played any of those Shin Megami Tensei games as a kid – adding an additional level of depth to the gameplay beyond simply catching new monsters; with the additional caveat of needing a guide if trying to breed a specific monster.

And while the battle mechanics aren’t nearly as polished as Pokemon’s, with no true metagame, one gets the impression that Dragon Quest Monsters did not set out to create a competitive metagame-type experience, more so a “isn’t it fun to collect all these cool-looking monsters!” experience, which it succeeds at exceedingly well.

*Behold: monster variety!

*Behold: monster variety!

You, the player, start off with a simple Slime; then you grow your party exponentially, often breeding the same monsters you spent hours bonding with into new creatures that carry on the legacy of violence as you cut through the numerous portal worlds scattered throughout this simultaneously charming and horrific computer game.

Dragon Quest Monsters is the perfect handheld game and, back in 1998, was a “must-play!” title. It still is, especially if you’re into computer games of the retro-persuasion. However, it is not always a thrilling experience; there is a lot of monotony here – grinding, walking back and forth from the breeding grounds to the farm, and aimlessly wandering in maze-like portal worlds are a common occurrence.

Fortunately, Dragon Quest Monsters can be played with one hand on any platform. If you are proficient in the ancient technique known as “the claw,” you can access everything you need with your thumb and index finger. This is helpful in instances where you need to perform a monotonous task, such as grinding a newly hatched monster, but also want to lie down on your couch, watch “Space Captain Harlock: Arcadia of My Youth,” and engage in a debate about the strengths of various fictional Dragon Ball characters on your phone – all while a three-month-old baby sleeps on your chest; a quadruple-task I often found myself engaged in.

*The art of doing four things at once.

*The art of doing four things at once.

Computer games are just that: games; some may go out of their way to drive a point into your brain; others are simply focused on providing an entertaining experience that distracts you from the horrors of reality. Dragon Quest Monsters falls into the latter category, but my hyperactive and stupid mind makes a mountain out of a molehill, and suddenly Dragon Quest Monsters is about factory farming.

Dragon Quest Monsters does not try to make you a vegan; it does not try to solve problems of morality; it does not try to unravel the mysteries of life. It’s just a fun little handheld game with an addictive monster-collecting aspect that kept this writer with an overactive imagination entertained for about fifty hours.

And in this writer’s opinion, that’s fine. Computer games don’t need to have an overt agenda. In fact, they probably shouldn’t have one at all; but that won’t stop me from having one.

While reading this article, if just one person reconsiders how we – as a species – treat animals, then I consider that worth the time spent typing out all these words.

And in my sorry way, I have achieved something.

As always, if you get bored, do something else.

(Originally published on 8/5/2023)

#ComputerGames #DragonQuestMonsters #Ethics #Essay #AudioEssay