Tactics Ogre: Reborn – Ruminations on Resentment, Regret, and Retribution

Introduction or: a brisk summer breeze and fishing in the pond

Every summer as a child, my parents would send me to stay with my grandma in Charleston, South Carolina. It was during one of these summers, when I was around nine years old, that I met a boy who quickly became one of my closest friends. He lived just three yards away from my grandma, behind a huge pond with an ever-flowing fountain. And when I say “yards,” I mean literal yards, not the unit of measurement. I would walk through those same yards to get to his house, much to the annoyance of their owners. We would often fish in the pond behind his house, but I never caught anything. I was always lousy at fishing as I didn’t have the patience for it. On the other hand, my friend was very good at it – he was good at a great number of things. He would always release the fish back into the pond, “catch and release” he would call it. On one occasion, he accidentally left a hook in a fish’s mouth before releasing it. I remember this vividly because someone else caught the exact same fish, hook and all, later that summer, right in front of my friend and me.

My grandma still lives in the same house. I still visit there often. Not much has changed, which helps ensure I don’t forget these little things.

My summer-friend was far more athletic and charming than myself. He was very interested in outdoor endeavors, while I was, and still am, a more reclusive, indoors-oriented person. He had many friends in the neighborhood, most of whom I did not get along with due to my “strange” disposition. Despite our differences, we were both sharp and like-minded in many ways, and we both enjoyed playing computer games. I had unfettered access to all types of computer games, which could be considered questionable parenting, while he was on a much tighter leash and lived vicariously through me when it came to gaming. Every summer, I would come to Charleston with new games, and he would be fascinated with them, often coming over just to watch me play for hours.

During the summer of 2001, my summer-friend’s friend lent me their Game Boy Camera to “play with for the week,” and I subsequently traded it at the local Babbages for in-store credit. Babbages was like a proto-GameStop. Looking back, I have no idea what I was thinking; it was a bad idea. I wasn’t the nicest kid in the world, and I didn’t particularly like the girl who lent me the Game Boy Camera to begin with. Later, after a series of dramas, my grandma and I had to return to that same Babbages, repurchase the Game Boy Camera, and return it to its rightful owner – a story my summer-friend still tells to this day.

These events are significant because thanks to that in-store credit, I was able to purchase a used copy of Final Fantasy 7. At the time, my ten-year-old brain was drawn to the spiky-haired guy holding a big sword on the cover. Throughout the remainder of that summer, I spent countless nights playing Final Fantasy 7, and looking back, I realize this game played a pivotal role in shaping my current gaming preferences.

*The same 2001 copy of Final Fantasy 7, purchased with dirty in-store credit (it’s missing disc 2)

*The same 2001 copy of Final Fantasy 7, purchased with dirty in-store credit (it’s missing disc 2)

It’s funny how such a careless action on my part would eventually result in a lifelong passion for oversized swords, messy hair, and, most importantly, Japanese role-playing games. Despite being a bad decision at the time, trading that girl’s Game Boy Camera for in-store credit ultimately led to some positive outcomes.

I wonder, if my younger self were given the power to turn back time and rewrite history, would I still make the same decision to trade in a borrowed Game Boy Camera for in-store credit or would I erase the whole situation to avoid the shame and subsequent verbal lashing from my grandmother, and in doing so, repair my relationship with the kind girl who had lent me the camera in the first place? What would I be doing now if I hadn’t played Final Fantasy 7 that fateful summer? Would I be obsessed with the Madden series instead, or something equally as dull? Maybe I would be making seven figures as the CEO of a successful company instead of writing this article? Perhaps I would have been hit by a car while riding my bike in 2018? I guess we will never know.

How is this related to Tactics Ogre? Well, having played Final Fantasy 7 in 2001, I was inclined to play anything with the name Final Fantasy on it. In the summer of 2004, the Game Boy Advance was all the rage, and having saved up my allowance, I purchased Final Fantasy Tactics Advance by virtue of brand-name and cover art alone. Oddly enough, that same summer, my friend picked Tactics Ogre: The Knight of Lodis with his allowance money. We played both games in tandem that summer. He often suggested that I give his game a try, claiming it was fantastic, and I would occasionally glance at his screen and notice how similar it looked to what I was playing. However, as the contrarian that I was (and arguably still am), I believed that Final Fantasy Tactics Advance was the better game and that I, with my superior gaming wisdom, had made the better choice. I had no need to play Tactics Ogre.

Due to this left over contrarianism from 2004, I was always hesitant to play the Ogre Battle series. Little did I know at the time, Tactics Ogre was created by the same team that later went on to create the Final Fantasy Tactics series. The original developer, Quest Corporation, was absorbed by Square in 2002 and renamed Square Product Development Division 4. Tactics Ogre: The Knight of Lodis was their last official game as Quest Corporation, having made the original Ogre Battle: March of the Black Queen in 1993 and its sequel Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together in 1995, both for the Super Nintendo and both named after Queen songs. Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together would later be remade for the PlayStation Portable in 2010 and then re-released again as Tactics Ogre: Reborn for multiple consoles, the final version being the one covered in this article.

*Two great GBA games battle for the attention of two 13-year-old kids

*Two great GBA games battle for the attention of two 13-year-old kids

In conclusion, it turns out my friend was playing an older game that could be seen as the spiritual precursor to what I was playing that summer. Would this additional knowledge have made a difference to thirteen year old me? Would I have been more open to my friend’s recommendation? Probably not. However, one thing is certain: if I could turn back time and try Tactics Ogre: The Knight of Lodis back then like my friend had suggested, I would have gotten into the Ogre Battle series much earlier than, well, a month ago. Perhaps my entire gaming history would be different?

Plot or: choices choices choices

Tactics Ogre: Reborn is a remake of Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together, and it doesn’t deviate much from the original game’s plot. The player assumes the role of a young man named Denam Pavel who travels the islands of Valeria in an attempt to end the seemingly endless power struggles by unifying the multiple warring factions; eventually leading an army of his own to make this dream a reality. Valeria is split by multiple factions vying for control of the islands, such as the Walister, the Galgastani, the Bakram, and the Dark Knights Loslorien, to name a few. Denam’s journey is marked by numerous decisions that shape the future of Valeria, for better or worse.

*Denam, the map of Valeria, and the crests of warring factions

*Denam, the map of Valeria, and the crests of warring factions

Prior to the events of the game, Denam resided in the town of Golyat with his sister Catiua and closest friend Vyce. They led peaceful lives until the Dark Knights Loslorien swept through, brutally massacring most of the town. As a result, Vyce lost his family, and Denam’s father was kidnapped, igniting a burning desire for revenge within our three main characters. This culminates in our heroes planning retribution against the Dark Knights and eventually joining the Walister Resistance, a group fighting against the Dark Knights, to further this goal.

The Walister Resistance consists of people who identify themselves as Walister, a “race” of people that inhabit the region around Golyat. Although they are categorized as a separate race within the game’s fiction, they appear and sound much like every other race of people in Valeria. In Tactics Ogre, the concept of race is more akin to nationality than any physical characteristics, and this idea plays a significant role in several of the game’s overarching themes. For instance, despite their similarities, the races are still constantly warring and killing each other, but why? Something we’ll get into later.

Under the shrewd leadership of Duke Ronwey, the Walister Resistance professes to seek only the end of the occupation of their territories by the Dark Knights and Galgastan. However, their real objective is to attain power and claim the entire land of Valeria. It remains uncertain whether Denam, Vyce, and Catiua share the Walister’s nationalist agenda, as their primary motivation is revenge against the Dark Knights, but they are more than willing to tag along killing those who oppose the Walister Resistance unquestionably, at least early on.

The Dark Knights Loslorien, the Kingdom of Galgastan, and the Bakram have formed a tentative alliance to suppress the Walister resistance, with all factions ultimately vying for control over the islands of Valeria. As one can imagine, this creates a politically complex situation, as all alliances in Valeria exist on a razor’s edge. Denam fights alongside Duke Ronwey’s resistance until a rift develops between him and Vyce due to objections with the Duke’s methods, ultimately revealing the fragility of their friendship. This conflict marks a crucial turning point in the game’s narrative, and the player’s choices at this intersection determine the ultimate fate of Valeria.

*Denam, about to make a very important choice

*Denam, about to make a very important choice

Tactics Ogre is the type of game where you seemingly make all the right choices but your entire family still ends up brutally murdered. These choices are a fundamental aspect of what makes the game’s plot so captivating. There are three primary routes determined by choices you make throughout the game: chaos, law, and neutral – similar in nature to the Shin Megami Tensei series. Each route unfolds differently, dictating who joins your resistance, who perishes, and ultimately how the story ends. In each route, numerous smaller choices impact less significant events. Therefore, even the most mundane choices have significant consequences, often leading to decisions made long ago returning to haunt you.

Tactics Ogre stands out from other role-playing games due to the absence of clear “good” and “bad” endings, as each plot-thread was given equal care and consideration by the writing team. Additionally, all choices within the game are somewhat ambiguous – what may seem like the morally righteous decision at the time can lead to dire consequences later on. As a result, players may encounter numerous “what the @#$%” moments as they witness the aftermath of their seemingly righteous choices.

Tactics Ogre’s ambiguous choices have a downside in that they can prevent access to certain characters and sidequests. For instance, in the early stages of the game, I wanted to recruit a certain cool character, so I made what seemed like an obvious choice to align myself with her side. However, as a consequence of that choice, she immediately died. Conversely, if you make the opposite choice, that character will hate you, and you’ll need to make a series of correct choices going forward to persuade her to join your cause. None of this can be deduced simply by playing the game as is, which is why a guide is essential if you want to unlock all the game has to offer.

While I am usually of the opinion that a guide should not be necessary to fully experience everything a game has to offer, the uncertain nature of Tactics Ogre’s choices can be exhilarating at times. Watching the unforeseen consequences of your decisions unfold can be an enjoyable experience, even if they occasionally result in unsatisfactory outcomes. This helps reinforce one of the game’s primary themes, that of loss and regret – the notion of “if only I could go back and do it all over again.”

*Introducing the World Tarot

*Introducing the World Tarot

But don’t fret – you can go back and do it all over again! To further add to the game’s complexity, Tactics Ogre: Reborn incorporates a unique time travel system, known as the World Tarot, which enables players to revisit previous points in time and make different choices, effectively rewriting history. This allows players to explore alternate paths and outcomes, and a substantial portion of the game’s endgame is dedicated to utilizing this feature to recruit previously missed characters and observe the various consequences of different decisions.

The themes of regret and consequence are central to Tactics Ogre’s narrative, and the time travel aspect reinforces these themes by providing the player with a glimpse of what could have been – oftentimes, the results are equally as dire. However, the brilliance of this system lies in its optional nature; the game never forces you to use the time travel mechanics, allowing your choices to remain as permanent as you desire. It’s akin to save-scumming, just more sophisticated.

With that in mind, my recommendation on a first playthrough is to play completely blind. Even if you don’t get all the characters or outcomes you would like, you can always rewrite history.

Themes or: ruminations on resentment, regret, and retribution

In Chapter 4 of Tactics Ogre, a little girl is shot in the back with an arrow and dies instantly; a random act of violence highlighting the game’s dark tone; sometimes bordering on Berserk-levels of chaos. Tactics Ogre harnesses this darkness to explore weighty themes concerning human nature, power, friendship, envy, chaos, regret, and war; also delving into philosophical concepts such utilitarian ethics. The game challenges players to reflect on its themes and arrive at their own conclusions without imposing a specific message; and in line with the game’s intent, I will attempt to do that.

Envy serves as a potent driving force behind human motivation in the game’s narrative. The deadly sins of greed, envy, and pride are exemplified most in the character Vyce, Denam’s childhood friend. Through the interactions between Denam and Vyce, their long and storied history is revealed. However, despite their long friendship, Vyce always maintains a slightly holier-than-thou attitude when speaking with Denam and tends to adopt a tone of mockery around him.

Denam’s upbringing was filled with love and attention from his caring father. In contrast, Vyce was raised solely by his abusive and alcoholic father. Vyce frequently references this difference, revealing his envy towards Denam’s favorable circumstances. Additionally, Vyce hints at his love for Denam’s sister, Catiua, and drops subtle clues that he feels jealous of the attention she lavishes on Denam, while ignoring him completely. Despite initially viewing Denam as a role model of sorts, Vyce’s perception of him shifted at some point, morphing into envy and resentment instead.

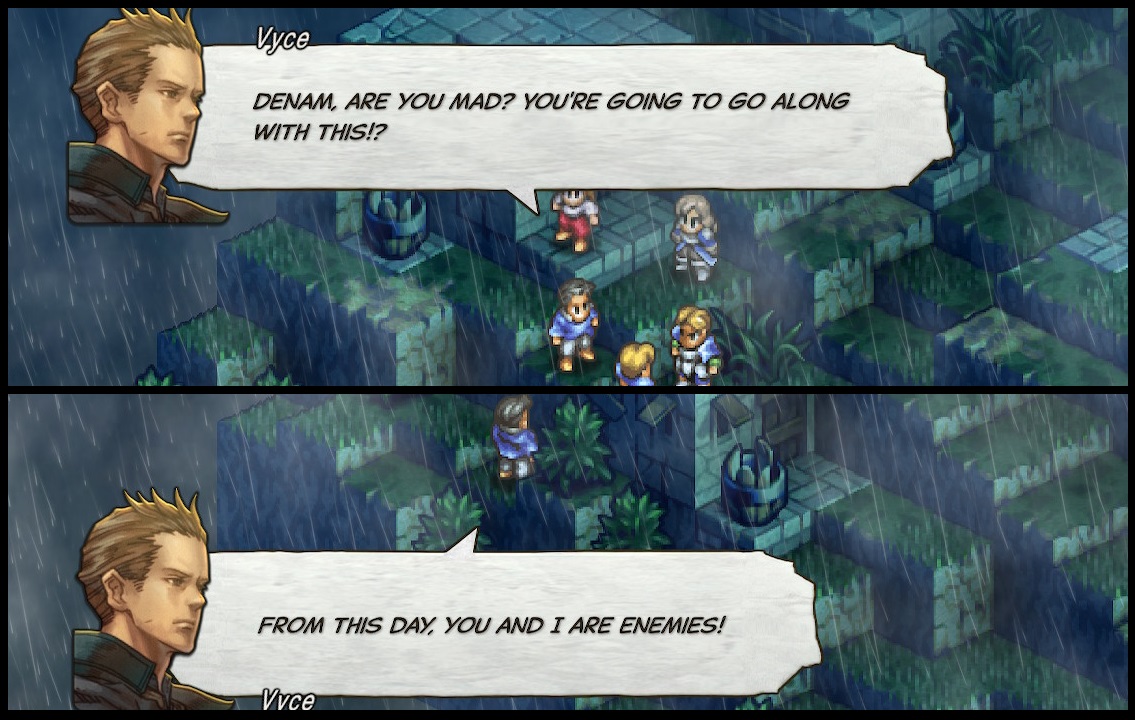

Early in the game’s plot, Denam is tasked with committing a village massacre to advance the Walister agenda. The slaughter is to be disguised as a Galgastani attack to help rally the local villages to the Walister cause. Denam has a choice: either comply with this plan or refuse and be branded a traitor, thus risking the blame for the massacre and losing all ties with the resistance. If Denam refuses to carry out the slaughter, Vyce scolds him, accusing him of being a traitor and betraying the Walister cause; Vyce argues that Denam should “see the big picture” and declares him his mortal enemy. Conversely, if Denam agrees to the slaughter, Vyce still scolds him, labels him a murderer, and claims they are mortal enemies. In both cases, Vyce appears to be taking the moral high ground over Denam.

*Vyce has no real principles

*Vyce has no real principles

Upon examining both outcomes of Denam’s decision, it becomes apparent that Vyce’s opposition is not based on genuine principles, but is rather an excuse to assert his dominance over him, driven by feelings of insecurity. Vyce conceals his true envious motivations, using the situation as an excuse to justify his long-felt jealousy and hatred toward Denam. This envy alone drives his behavior, nothing else. In the “chaos” route, during Denam and Vyce’s final confrontation, Vyce even admits to this, confessing his jealousy towards Denam outright, including his upbringing, kind-hearted nature, athletic ability, and relationship with Catiua.

The relationship between Vyce and Denam captured my attention since I have experienced similar emotions of envy towards my own friends, specifically jealousy towards their perceived superiority in certain aspects of life when compared to myself. For example, my summer-friend was more athletic and popular than I was. My high-school friend could play multiple instruments and was motivated enough to complete college. Why can’t I be like them? It’s easy to play the victim instead of examining your own faults and improving yourself. Vyce’s behavior reminded me of what I might do if I succumbed to the darker facets of my own personality. Ultimately, I saw myself in Vyce; and that’s a tad bit scary.

Denam opting to spare the lives of innocent people is undoubtedly a morally correct decision. However, if he were to choose to carry out the massacre instead, Vyce’s opposition to this act would place him in the morally superior position. This situation raises an ethical quandary because Vyce’s motivation for opposing the massacre is purely driven by his envy for Denam. Therefore, he opposes the slaughter only out of contrarianism, not because it would be the morally righteous course of action. This presents an intriguing dilemma in which individuals can inadvertently do good deeds, even if their initial motivations stem from a negative place; begging the question, does motivation really matter or are outcomes the only important thing to consider when evaluating a situation?

*Trolley Problem: Reborn

*Trolley Problem: Reborn

Arguably the game’s most important theme is moral ambiguity, and this is illustrated in almost every scene. It also raises questions around utilitarian ethics. For instance, in the previous example of the town massacre, ironically, the decision that results in better overall outcomes for our main characters is the slaughter of innocent townspeople. This raises an interesting point that morally reprehensible acts can sometimes lead to overall positive outcomes. It’s like a hyper-utilitarian game of chess or the trolley problem, where the question is whether slaughtering an entire village now could save hundreds of people later; but how could anyone ever truly know that? In Vyce’s situation, even though he has no real principles, his hatred and drive to kill Denam could inadvertently save a village full of people; he’s acting out a version of the trolley problem that he’s not even aware of.

Tactics Ogre constantly reminds the player that despite Denam’s pure motives, he is still taking lives and imposing his moral philosophy on the lands of Valeria, much like the factions he fights against. This begs the question: how is Denam’s resistance any different from the Galgastani or the Bakram? Ultimately, all parties seek to end war and rule over Valeria; they simply use different ethical frameworks to justify how they achieve this result. After all, every would-be conqueror believes they are doing what’s right. Even the Dark Knights of Lodis, arguably the most morally reprehensible faction in the game, seem to grasp this concept, their leader often using it to justify their survival-of-the-fittest philosophy.

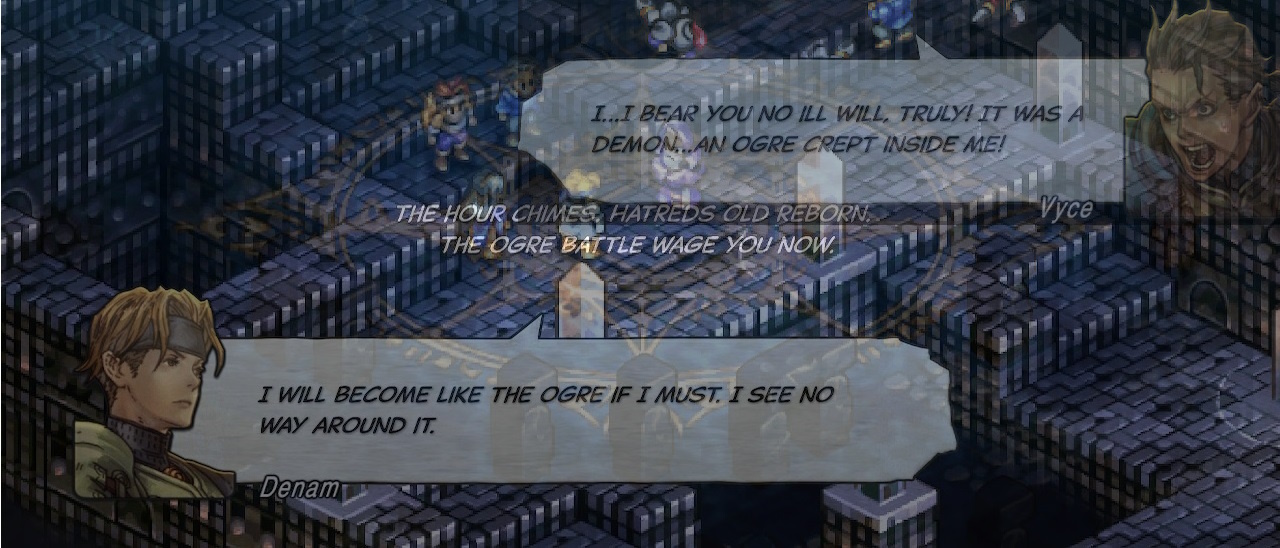

Expanding on the theme of moral ambiguity is the concept of the “ogre,” which is referenced throughout the narrative. While the game’s lore features a historical “Ogre Battle” between humans and ogres, the term “ogre” in the context of the story refers to the idea of doing monstrous things to achieve one’s goals. Denam is repeatedly asked whether he has the wherewithal to “become like the ogre” in order to achieve his vision, or in other words, if he is willing to do whatever it takes for the betterment of Valeria. This concept permeates the narrative, adding another layer of complexity to the game’s exploration of morality, raising questions about the cost of achieving one’s goals and the limits of acceptable behavior in pursuit of a noble cause.

* The Ogre Battle rages on

* The Ogre Battle rages on

The question of why people go to war is one that Tactics Ogre does not attempt to answer, but it certainly raises thought-provoking questions and provides some clues. Despite the existence of multiple races in Valeria that share similar appearances and cultures, the factions still engage in conflicts that are obviously not based on race or nationality directly, even though the faction leaders may say otherwise; it would be easy to unify Valeria if those were the only points of contention. In my view, two primary motives underlie these wars: revenge and moral sunk cost.

The first reason is simple: revenge. This is exemplified time and time again through a recurring motif that I call “generational despair.” This concept is depicted in characters seeking retribution for their loved ones who were killed in previous battles, even those that occurred generations ago. The game’s battles feature countless enemy leaders citing reasons such as “you Walister dogs killed my mother” to justify why they fight. Even the protagonists themselves become motivated to fight out of a desire to avenge their murdered families. This concept of “generational despair” highlights how the pursuit of revenge can spiral into a cycle of violence, perpetuating conflicts that span generations.

Even the game mechanics serve to further emphasize this theme by demonstrating how minor battles can escalate into more revenge-driven conflicts. For instance, after eliminating an enemy unit in one battle, their spouse may appear in the next battle, seeking revenge. Of course, in the interest of unifying Valeria, you have to eliminate the vengeful spouse as well, thus continuing the cycle of violence.

*Young Denam; a case study in generational despair and moral sunk cost.

*Young Denam; a case study in generational despair and moral sunk cost.

This brings us to what I believe is the final motivation behind these wars: moral sunk cost. Similar to the sunk cost fallacy, which causes people to persist in a certain course of action simply because they have invested a significant amount of time or money into it — after all, why waste all that effort? — moral sunk cost applies this principle abstractly to the morality of one’s actions.

Suppose you embark on what you believe to be a morally righteous goal, such as a religious crusade. However, along the way, you cause death, destruction, and injustice to everyone you encounter, all without making any real progress towards your goal. At this point, upon reflection, you have only two options left: stop your crusade altogether or continue. But why would you stop now? Were all those lives lost in pursuit of your crusade really worth nothing? Was the destruction you caused truly meaningless? Surely, this was all for the greater good, right?

I believe that this mindset drives much of the fighting in Valeria, and perhaps in the real world as well. Often, we convince ourselves that we are doing the right thing, even if there is collateral damage along the way. We may discover later on that we were mistaken, our goals were actually not morally righteous after all. However, the thought of admitting to such a mistake is unbearable, as it would mean accepting true responsibility for all the bad things we did while attempting to achieve our goals. We would effectively be admitting that we became like the ogre. Consequently, we resort to justifications such as “we must continue, or their lives were lost for nothing!” or “my father died fighting for this goal!” as a means to ignore the wrongs that have already been committed. Much like the vengeful spouse who seeks retribution for their fallen partner and will do anything to achieve this retribution, we simply cannot move on.

Lastly is the theme of regret. By the end of the game, Denam and others have a great many regrets, especially around some of the pivotal choices made throughout the story. At the time, everything seemed for a greater good, but looking back later on … was it really worth it? In pursuit of this grand vision of unification, did Denam sacrifice too much? Was there anything he could have done differently?

Back in high school, I broke the heart of my high school sweetheart, ruining our relationship forever. If only I hadn’t made that one tiny decision, maybe we would still be together? It’s hard to say. I can’t help but wonder what could have been if I had acted differently.

Everyone has regrets – I guess you just have to live and learn.

Gameplay or: more time travel shenanigans

Enough about the narrative elements of the game. Tactics Ogre: Reborn is a computer game, after all, so what about the gameplay? Is it actually fun to play? The simple answer is: Yes. At the time of its release, Tactics Ogre was revolutionary in its design, and it had a significant impact on the tactical role playing game genre that we know today. Although similar games preceded it, such as the Shining Force or Langrisser series, Tactics Ogre propelled the genre into the limelight and ultimately perfected the formula.

Tactics Ogre’s battles take place on large, isometric battlefields of various settings, such as mountains, tundras, grasslands, volcanoes, castles, and towns. You control a party of up to 12 units against the opposing party. The typical objective of each battle is to defeat the enemy leader, and in rarer cases, defeat every enemy on the map. Each unit moves in a turn-based fashion based on its recovery time or speed, and each unit has a specific role with strengths and weaknesses determined by their class.

During a battle, you need to consider various factors, including the weather and the terrain of the battlefield, which often impedes movement. Smart movement decisions are pivotal to securing victory. Additionally, you can adjust the camera left and right in a “bird’s-eye view” mode, which provides a flat-plane view of the battlefield from overhead. This perspective is particularly useful since the terrain on many battlefields often blocks visibility of units.

*The battle begins!

*The battle begins!

Influenced by Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy, Tactics Ogre incorporates a fairly robust class system with over 15 classes, including several unique classes that are exclusive to specific characters. A standard unit can only have one assigned class, which can be changed at will outside of battle. In the Reborn version of the game, there is no class level, so changing a unit’s class does not reset their level to 1. Instead, the level they had before carries over to their new class, resulting in less overall grinding – always a plus for any role-playing game. Moreover, Reborn eliminates the archaic need of having to hit your own units to gain extra experience points during battle. Instead, experience is now aggregated and distributed equally to every unit that participated in the battle at its conclusion.

Classes in Tactics Ogre may appear boring at first glance, but there is a sneaky level of depth that is revealed when you peel back some of the layers. There is no dual-classing, which means there’s no skill mix-and-matching. A Knight is always a Knight, regardless of which unit uses that class. You cannot transfer Archer skills over to a Knight, as you can in the Final Fantasy Tactics series. However, every class can only equip four skills and four spells, with over 20 skills at their disposal. This means that even if you have two Knights in your party, they are unlikely to be using the same skills. Therefore, the same classes can fulfill different roles depending on their build or skill loadout.

For example, Knight 1 could have the following skills: Swords, HP+, Rampart, and Phalanx. This skill set would make Knight 1 a very tanky sword-wielder, capable of blocking enemy unit movement with Rampart and taking half damage from attacks with Phalanx. Meanwhile, Knight 2 could have a different set of four skills, such as Hammers, Pincer Attack, MP+, and Sanctuary. This skill set would allow Knight 2 to use hammers more effectively, function more as a damage dealer with pincer attack, have more MP for healing magic, and block the movement of undead units with Sanctuary. In this way, each knight fulfills a different role based on their specific skill loadout. On the other hand, if you have only one Knight in your army, you can select and adjust their skills before a battle based on the situation. For instance, if the battle includes undead units, it would be beneficial to use Sanctuary, but if not, it would be wiser to choose a different skill to optimize your chances of victory. This customization makes every unit distinct even if they share the same class, more akin to a chess piece than a computer game character.

Reinforcing the chess-like nature of Reborn over its predecessors, it’s not possible to simply overlevel your characters to overpower every encounter. Each stage of the story has a predetermined level cap, and surpassing that cap is impossible. This makes the act of powering through battles a thing of the past, particularly on your initial playthrough, and truly highlights the emphasis on this game being more about strategy than a typical role playing game where level holds way more significance.

The changes in the class and level systems in Tactics Ogre: Reborn create an experience that feels more like an advanced game of chess than a typical strategy game. Every decision made before battle regarding party formation, as well as every decision in battle, feels crucial, and even a single mistake can lead to dire consequences, really emphasizing the “Tactics” of “Tactics Ogre.”

*A battle scene, showing the birds eye camera and isometric gameplay

*A battle scene, showing the birds eye camera and isometric gameplay

As mentioned earlier, each unit can utilize four skill slots, with two different types of skills available. The first are normal skills that can be used in battle, while the second are “auto-skills” that have a chance of activating on a unit’s turn and can provide bonuses such as increased damage, reduced damage, or extra MP, among other things. In addition to skills, there are various types of magic available, including healing, damaging, and status ailment spells. MP is used for both skills and magic, a change from previous versions of the game that used both TP and MP. However, this consolidation works well in Reborn, putting the focus more on building and managing your resources to maximize your effectiveness in battle; as such, it is essential to prioritize positioning your units strategically and accumulating MP gradually, as MP begins at zero and increases with each turn; making MP a very valuable commodity.

A major change introduced in Reborn is the addition of buff-cards that randomly appear on the battlefield. These cards consist of “Physical Damage Up”, “Magic Damage Up”, “Auto-Skill Trigger”, “MP Gain Rate Up”, and “Critical Hit Rate Up”, and can be immensely helpful if you manage to collect them, easily turning the tide of battle in your favor. The unit that lands on the space where the card spawned will get the buff of that card, and a unit can have up to four of these buffs at once. A unit with four “Physical Damage Up” buffs will plow through enemy units, whereas a unit with four “Auto-Skill Trigger” buffs will activate their auto-skills almost every turn; depending on which auto-skills the unit has equipped, this can make the unit incredibly powerful.

The addition of buff-cards in Tactics Ogre: Reborn introduces a diabolical twist where enemies can also collect these cards and often prioritize doing so. This discourages stalling tactics as collecting buff-cards offers a significant advantage for whoever gets them first. If you try to stall out your enemy and wait for them to come to you, enemies may collect buff-cards during those turns, putting you at a disadvantage. Furthermore, enemy leaders are typically pre-buffed, making them more dangerous to begin with. Ultimately, the buff-card system encourages early and frequent movement, creating a high-risk, high-reward scenario that is actually very enjoyable when it pays off.

Although the buff-card system is interesting, it has a downside. The cards litter the battlefield midway through every battle, which is ugly and distracting. It would have been better to use less intrusive visual effects, such as small floating balls or auras, to avoid detracting from the beautiful isometric battlefields. Look no further than the screenshot below to see what I mean. It is a wonder that this design element made it beyond the testing phase without a workaround of some sort. Make no mistake, I like the addition of this mechanic as it adds additional strategic depth to the gameplay, however, it could have been implemented more elegantly.

*A battlefield littered with buff-cards

*A battlefield littered with buff-cards

Like many strategy role-playing games, Tactics Ogre includes permadeath for all units. Once a unit loses all their HP, they become incapacitated. Incapacitated units have a three-turn timer over their heads. If a unit is not revived after three turns, they die permanently. There are various methods of reviving incapacitated units, such as using a revival item or having a priest resurrect them mid-battle; but once the timer reaches zero, they are gone for good. This permadeath system fits well with the game’s overall dark themes, especially since loss and regret are so prominent within the game’s narrative. It makes sense that your soldiers can die permanently, and even significant characters can meet the same fate, which can significantly alter the story’s development.

However, it is unlikely that your characters will die permanently, if ever, and this is not because the game is easy. In fact, Tactics Ogre: Reborn can be quite challenging at times. The reason they won’t be dying often is because you can just go back in time and prevent a character’s death altogether – even mid-battle.

Playing on one of the game’s primary motifs, that of altering choices and consequences, the game features time travel not only as part of exploring the narrative but also within the battle system itself, using a system called the “Chariot Tarot.” This system allows you to return to any turn within the last 50 turns and start over from that point – if this sounds overpowered, that’s because it is.

*Save-scumming with the chariot tarot after the enemy parries my attack

*Save-scumming with the chariot tarot after the enemy parries my attack

The Chariot Tarot system is effectively a glorified save-scummer built right into the game. Moved your unit to the wrong spot, resulting in their death? You can go back five turns and prevent that from ever happening. Missed a critical attack on an enemy unit? You can go back and do something else, such as moving away and casting a buff spell instead, or just choosing a different attack such as in the video above. The possibilities for abuse are pretty much endless.

The Chariot Tarot system is really interesting and unique, but ultimately somewhat game-breaking as it trivializes much of the decision-making process during a battle, removing the element of permanence from your decisions. However, the beauty of this system is that you don’t actually have to use it; it is entirely optional. On the other hand, it takes considerable will-power not to use it, especially in the event of a character death. Truly this is the ultimate weapon of any battlefield, the power to manipulate time itself.

Outside of the core mechanics, Tactics Ogre: Reborn excels at the little things as well. For example, the sound design is incredible; from the satisfying click of every menu decision, to the way the main battle theme crescendos right when you start your first turn; everything comes together incredibly well. Even the voice acting, which was added for this version of the game, feels like it should have always been included. Truly everything about this game is polished to a tee, you can tell so much care was put into every little thing. There’s very little to criticize.

Conclusion: or an apology to my summer-friend

Tactics Ogre: Reborn is an outstanding game with engaging gameplay, a compelling story, and narrative themes that prompt introspection in a way that you may not have experienced since your broody teenage years, as evident from this article.

After six consecutive days of playtime, without playing anything else, I can confidently say that Tactics Ogre: Reborn captivated me from the start and kept me returning, even after completing the story for the first time, just to indulge in more of what the game had to offer; the amount of content this game provides is truly bordering on levels of generosity so great that even Bill Gates himself would be envious. Additionally, its flaws are so minor they aren’t really even worth talking about.

From the lofty themes and dark nature of certain parts of this article, one might assume that the game wears its themes on its sleeve in a pretentious manner, prioritizing its story and striving to seem intelligent over actual gameplay; however, this could not be further from the truth. The game tells its story in such an non-intrusive manner that you barely feel like you’re being taken out of the gameplay at all, as everything is done in engine without the need for cutscenes or other modern extravagances.

Looking back, I owe an apology to my summer-friend who had recommended the series to me earlier in life. He was right and, like Vyce, I was just being a contrarian. I missed out, but I am here now.

*My final savefile on the Nintendo Switch version of Tactics Ogre: Reborn

*My final savefile on the Nintendo Switch version of Tactics Ogre: Reborn

If I were given access to the World Tarot, would I turn back time and play the series earlier? Probably not. Experiencing Tactics Ogre: Reborn now allowed me to appreciate it in a different way, and if I played it earlier, I might not have enjoyed it as much. Besides, it was so long ago that the magic might have worn off by now. Also, I would seriously run the risk of becoming one of those “the original SNES version was better” purists; such hipsterisms frustrate even my own hipster sensibilities.

In conclusion, if you haven’t played the series before, Tactics Ogre: Reborn is a great place to start. If you’ve already played the earlier versions, it’s worth trying this version for the new gameplay mechanics, voice acting, and beautifully upscaled visuals (ignore the naysayers who complain about “smoothing”, the game looks great). If you’ve already played Tactics Ogre: Reborn and just wanted to read someone else’s thoughts on the game, then thank you for sticking around this long.

And remember, if you start to get bored … turn the game off and do something else. If you’re not having fun, it’s not worth it. Although, you won’t have this problem with Tactics Ogre: Reborn.

(originally published on 4/25/2023)