The Final Fantasy Legend – So Begins Our SaGa

Introduction or: So Begins Our SaGa

The year was 1989, Square’s president Masafumi Miyamota wanted to push Square into the handheld realm by releasing a game similar to Tetris for the Nintendo Game Boy. The big boss chose Akitoshi Kawazu and Koichi Ishii to work on this new title; both having worked on Final Fantasy II, and the bigger names at Square were already engaged on Final Fantasy III at the time. Kawazu was renowned for introducing some of the unconventional elements in Final Fantasy II, such as the keyword and activity-based progression system; both features either loved or vehemently hated by the fans (no in-between), as they were considered highly unorthodox at the time, veering from the more vanilla systems found in the Dragon Quest series and Final Fantasy I.

Miyamota’s plan to create a Game Boy game inspired by Tetris was a sound business decision at the time, but it took an unexpected turn when Akitoshi Kawazu, renowned for his unconventional approach, went against the boss’s decision and decided to develop a role-playing game instead. This move, partially motivated by Square’s primary audience of role-playing enthusiasts, was also the perfect chance for Kawazu to act on his ambitions and spearhead his own series. Seizing the opportunity like Oda Nobunaga in the face of overwhelmingly bad odds at the battle of Okehazama, Kawazu chose to build on the concepts he introduced in Final Fantasy II, with the goal of creating a series of his own quirky machinations.

To bring his vision to life, Kawazu enlisted a wide range of Square talent, including artists Katsutoshi Fujioka and Takashi Tokita, producer and designer Hiroyuki Ito, and renowned computer games composer Nobuo Uematsu (a true Final Fantasy Legend), to create the blueprint for his new series. The result was Makai Toushi SaGa (roughly translating to Devil Tower Saga) for the Game Boy, later released in 1990 in the United States under the name The Final Fantasy Legend; Square hoped this brand-naming-trickery would capitalize on the popularity of the Final Fantasy name in the west, which most likely annoyed Kawazu immensely. Nevertheless, Makai Toushi SaGa marked the beginning of a new series characterized by the strange and unorthodox – the SaGa series (note the capital “G,” which is necessary and cool); the weird little brother of Final Fantasy, always inclined to break the rules whenever the chance presented itself.

*SaGa logo and concept art by Katsutoshi Fujioka, humans alongside their in-game representation; nuke launchers, machine guns, and chainsaws in tow.

*SaGa logo and concept art by Katsutoshi Fujioka, humans alongside their in-game representation; nuke launchers, machine guns, and chainsaws in tow.

In the end, Akitoshi Kawazu’s ambition and Square’s marketing tactics paid off, as Makai Toushi SaGa became the company’s first game to ship over 1 million units. It has the unique distinction of being the first role-playing game for the Game Boy, and is even cited as having a significant influence on the creation of Pokemon. This was the beginning of the SaGa series, and while not super popular in the West, it has over 10 titles to its name and is beloved in Japan to this day; solidifying itself as one of the major players in the Japanese role-playing computer game pantheon and sits among Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest as part of the Square Enix “warring triad” of sorts.

Through the writing of this article (which I hesitate to call a “review” due to the subjectivity inherent to experiencing computer games beyond the most basic of artistic and programming competency), I intend to begin a series of articles covering each game in the SaGa series. Naturally, this will only include SaGa games that I can play in English, and may eventually culminate in a scathing critique of the mobile gaming scene by analyzing the mobile SaGa gacha game; something to look forward to for all my readers (none).

For this article, I played Makai Toushi SaGa, or The Final Fantasy Legend (which is the name I will be using going forward), on the Nintendo Switch version of Collection of SaGa. All screenshots and videos featured in this article were taken from my May 2023 playthrough unless otherwise noted.

Without further ado, let’s begin our SaGa.

A Short SaGa Story

As you wake up in your ragged bed and avert your gaze to the window, the bright yet somehow sickly sunbeams cause you to cover your eyes for a moment before focusing on a Tower in the distance; this Tower appearing to stretch through the green-tinted clouds forever. You sluggishly climb out of bed, put on your tunic and trousers, and attach your worn-out bronze sword to your belt. After nibbling some stale bread, you ready yourself to head outside; wishing you could rest longer, but you know the monsters become more active as the day goes on and Base Town needs protection. With that in mind, you gather your wits and make your way out of the dilapidated shack you call your home, stepping out into the town you know so well.

Almost immediately you hear screams of women and children outside the town walls, you rush through the gate and witness a terrifying scene: a massive mechanized goliath, armed with a gun-arm, mercilessly attacking a family, most of which have already been gunned down. However, a woman manages to avoid slaughter and rushes towards you, crying out for help. As one of many protectors of Base Town, you hastily charge towards the robot, drawing your blade and executing a quick upward slash toward the exposed tubing around the front of its shiny carapace. The blade makes contact with the demon’s metallic skin, but only grazes it. You realize that you have only a few uses left of your bronze blade before it shatters.

*A deadly robot approaches!

*A deadly robot approaches!

The metal monstrosity retaliates by knocking you back with its left arm, sending you crashing to the ground. As you lay there, staring up at the lone red light that serves as the robot’s eye, it raises its right arm – the blaster – and aims it directly at you. Panic sets in; you quickly grab the holster on your hip and pull out your laser pistol; dad’s old gun, nearly out of charge; a last resort at best. You take aim at the bright red light and pull the trigger; a blue bolt escapes the barrel; traveling elegantly through the air, piercing the eye of the beast. Almost instantly, the robot drops its arm and collapses to the ground, spewing sparks like blood as a sickeningly loud buzz emanates from the thing.

You have managed to survive this encounter, but how much longer can you continue living like this? The locals at Base Town claim that ascending the massive Tower in the middle of town leads to Paradise. However, those who have attempted the climb never return; likely why they call it the “Devil Tower.” Did those brave souls perish in their frailty, or did they reach Paradise?

Setting and Plot or: Devil Tower and Pals

The short story above may have been something my ten year old brain imagined when playing The Final Fantasy Legend on the Game Boy using one of those tiny light accessories that clipped on the console while riding in the back seat of my dad’s car at night on a road trip to one of my grandparent’s houses in Athens, Georgia (that I, of course, did not want to go to); maybe not quite as detailed or elegant, but something along those lines. In retrospect, the brilliance of these “low-graphics” games lies in their ability to inspire players to imagine a much more detailed and nuanced world than what is presented on screen, filling in the gaps imposed by the hardware’s limitations. Much like reading a good novel, playing these games encourages the player to develop their own unique interpretations and, at times, come up with their own character backgrounds and lore; quintessential role-playing personified with a green tint.

*Carpet? Beach? Giant Pineapple? You decide!

*Carpet? Beach? Giant Pineapple? You decide!

Final Fantasy Legend may not have the most visually stunning graphics, but that’s not to say the game lacks an imaginative story or rich setting. The game uses its limited tilesets to portray a grim world spanning from medieval castles to futuristic skyscrapers; unforgivably sci-fi in its presentation; mixing multiple genres of fiction into one, much like an Ursula K. Le Guin novel. This blending of genres is key to the SaGa aesthetic, and The Final Fantasy Legend is the perfect “blueprint” of sorts, showcasing things to come in future SaGa games, even if it is a bit unfocused in its execution.

The Final Fantasy Legend’s overarching plot revolves around an unnamed hero’s journey to climb a Tower in order to reach Paradise, venturing through four different worlds along the way. The player starts in Base Town, making their own party of four heroes by hiring help from the local guild, selecting heroes from three different races: human, mutant, or monster. This level of party customization, which includes the ability to name your characters, contributes to the “fill in the gaps” nature of the game. In true role-playing fashion, as characters do not have their own backstories, players are encouraged to come up with their own; although, I was lazy and named my heroes after family members; the monster in my party being named after my wife.

*The Tower, as depicted in the game’s manual.

*The Tower, as depicted in the game’s manual.

The game’s world is composed of four distinct “world-layers,” each accessible by different floors of the Tower. These world-layers are the World of Continent, Ocean, Sky, and Ruin. Each of these world-layers features its own overworld map, distinct towns and dungeons, and different modes of transportation. Continent is a medieval fantasy world, Ocean is a waterworld that must be traversed by the use of moving islands, Sky is a world of clouds traversable only by a flying machine, and Ruin is a gritty post-apocalyptic hellscape. Trying to understand the absurd sacred geography of this land proves impossible; how does a Tower pierce each level? How is an ocean floating above a large continent? What force is holding this together?

The hero’s journey starts in the world of Continent, where three power-hungry kingdoms are locked in a constant state of war. To progress beyond this world, the hero must acquire a magical sphere that serves as the key to a sealed door in the Tower. After unlocking the door and ascending several floors, the hero reaches another sealed door that demands a new sphere. To progress further, the hero must locate the entrance to the next world and overcome its own unique set of challenges to obtain the next sphere. This process repeats through each world until you reach the top of the Tower. Each world resembles a new computer-gamey level of sorts, a problem to solve in pursuit of Paradise; feeling like different universes altogether, separated only by doors in the Tower; similar to the paintings found in Super Mario 64.

*The entrance to the Tower in the World of Continent, sealed by magic of black.

*The entrance to the Tower in the World of Continent, sealed by magic of black.

As you ascend the Tower you encounter the archfiends – four kings who govern each world. These archfiends are based on Japanese spirits, which themselves were based on the four symbols of Chinese mythology: Genbu the Black Tortoise, Seiryu the Azure Dragon, Suzaku the Vermillion Bird, and Byakko the White Tiger. Each serves as an obstacle in your path to Paradise, often in possession of the spheres needed to climb the Tower.

As a side note, each of the archfiends encountered in The Final Fantasy Legend have become staple bosses in the Final Fantasy online computer games. In Final Fantasy XI, they are referred to as “Notorious Monsters,” while in Final Fantasy XIV, they appear as bosses in dungeons and trials; as a side-side note, Final Fantasy XI features a skill-based leveling system and hits on several hallmarks of the SaGa series; like its pseudo-openworld, odd story structure, unique character progression systems, and genre mixing; to top it off, the original director was Koichi Ishii, who worked with Akitoshi Kawazu on the SaGa series. One could argue that Final Fantasy XI shares enough in common with the SaGa series that it should be considered an honorary SaGa title.

One example burned into my brain illustrating the prominence of the archfiends is the majestic fire bird Suzaku, who resides in the World of Ruin. Once you arrive in this world, you find a futuristic post-apocalyptic wasteland leveled by what appears to be a nuclear holocaust, complete with roaming zombies and mutated animals. Before you have a chance to gather your bearings, you encounter Suzaku; seemingly invincible and ready to destroy your entire party. It quickly becomes apparent that the nuclear holocaust was not the work of humans but of Suzaku herself. The player has no choice but to run, escaping underground where Suzaku can’t follow. You are relentlessly pursued by Suzaku until you discover the secret to defeating her. This game of cat and mouse, combined with the unique arena it takes place in (and the fact you get to ride a cool Akira-like motorcycle), creates one of the most memorable and engaging experiences in the game.

*Suzaku relentlessly pursues the party.

*Suzaku relentlessly pursues the party.

Late in the game, In true “grimdark” fashion, while climbing the Tower, our heroes come across a room containing four corpses, some of them children. The room is filled with bookshelves, and upon reading some of their contents, it becomes apparent that the bodies belong to a family that attempted to ascend the Tower but perished right before reaching the top; one wonders how they made it that far without the spheres, but that’s a question for another time. The family left behind a series of messages about the Creator, who constructed the Tower, but the messages are incomplete and leave the player guessing over their actual meaning. Without spoiling anything, unraveling the mystery of the Creator and discovering the secret of the Tower make up the remainder of the game’s story.

The Final Fantasy Legend is certainly not winning any Hugo or Nebula awards for science fiction story of the decade; however, the game’s unique genre blending and mature tone are undoubtedly remarkable for its time, particularly considering it was released for the Game Boy, a console with a primary demographic of children, in 1989.

Gameplay or: Unknowable Systems, the Savestate Ouroboros, and Computer Game Crypticism

SaGa games have a reputation for gameplay systems that are mysterious or downright nonsensical in their machinations. This reputation likely stems from the very first game in the series, which happens to be the subject of this article. From random stat increases to miraculously learning (and unlearning) spells, there’s a lot that doesn’t make immediate sense in the first SaGa game. Many of these elements are retained in future SaGa games, albeit far more refined and, in most cases, sufficiently explained. However, The Final Fantasy Legend fails to explain most of its gameplay systems, relying on the player to have the original paper manual to discover these details, but even the manual (which is available on the Internet Archive) is lacking sufficient information to fully explain the underlying clockwork at play. As a result, you will most likely end up dying multiple times early on, wasting powerful items and spells while trying to figure out what they do, even losing characters permanently if you’re not careful.

The core mechanics of The Final Fantasy Legend are reminiscent of its predecessors, especially Dragon Quest. You take control of a party of up to four characters; navigating towns and dungeons in pursuit of finding Paradise while completing quests and contending with random encounters along the way. The initial challenge may seem overwhelming, but with just a few minutes of grinding and trial and error, the game quickly becomes more manageable, feeling more like a brisk stroll than a competitive marathon. Unlike other games of its time, there is a surprisingly low amount of grinding required to complete the game. In my last playthrough, I only needed to grind once early on, which was a refreshing change of pace.

The game’s turn-based combat is refreshingly old-fashioned, devoid of any fancy tricks or gimmicks, and identical to Dragon Quest in its straightforward “select actions, characters perform actions, monsters perform actions” simplicity. Attacks can only be made with equipped weapons or spells, and there are no flashy super moves except for certain weapons that have special effects. These weapons range from medieval armaments to science fiction lasers and even nuclear bombs; each weapon has a specific number of uses, making inventory management as important as the battles themselves. Because turn order is solely based on a character’s agility stat and nothing else, battles become pleasantly predictable albeit somewhat samey and boring later on once the “new game” excitement wears off.

Overall, The Final Fantasy Legend’s battle system is not particularly remarkable, especially given its age, and you may have already played games with similar combat systems that are more refined and engaging. As such, this is very much a “you have to be in the right mindset to appreciate it” type of experience.

*A battle with the archfiend Byakko.

*A battle with the archfiend Byakko.

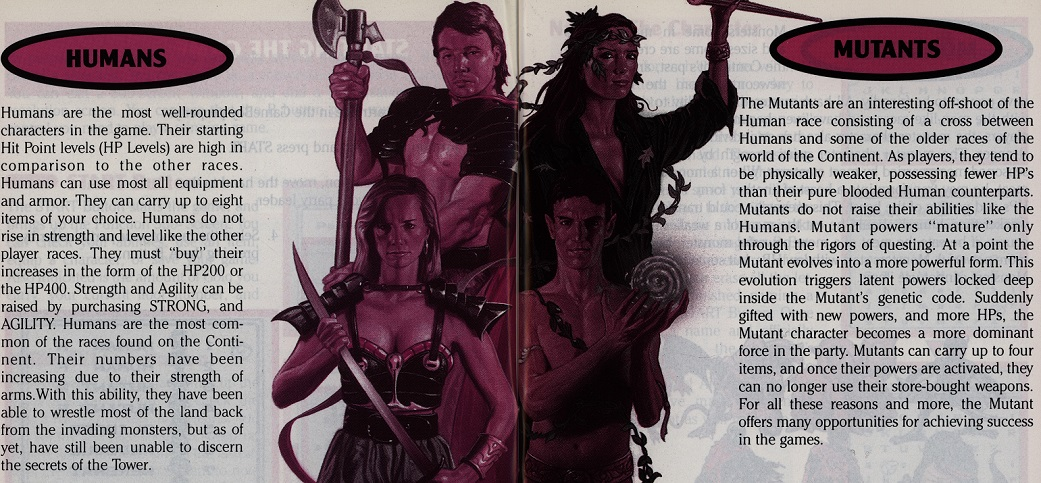

The topcoat of paint may seem conventional, but The Final Fantasy Legend starts to differ from its role-playing computer game contemporaries by way of its underlying systems, specifically its lack of traditional experience based leveling, instead favoring a three-pronged approach to leveling character statistics, otherwise known as a convoluted mess. Clearly inspired by Akitoshi Kawazu’s “usage based” skill up system in Final Fantasy II, but also not really. In a bizarre decision, perhaps to align with the game’s lore, the three playable races utilize different leveling systems entirely. Imagine three role-playing game leveling systems jammed into one game – that’s The Final Fantasy Legend. Don’t worry, we’ll get into it.

What’s a role-playing game without a bunch of normal humans running around? Somehow permeating every fantasy realm, breeding like rabbits, with their pale clammy skin and overall poor hygiene; naturally, humans are the default choice when making a character in The Final Fantasy Legend. While they can do anything, the concept of them being a jack of all trades, master of none (better than master of one) falls flat as they aren’t passably good at anything, especially compared to their peer: the mutant.

Humans have the ability to use any item in the game but cannot naturally learn spells. Instead, they must equip spell books, which are useless since humans are terrible with magic, this allows you to ignore magic completely on a human character which frees up their limited inventory space for lots of weapons, armor, and healing items. This makes humans most suitable for carrying around lots of atomic bombs, pistols, plasma swords, and elixirs.

Human stats progress in a very unconventional way. They can only increase stats by chugging potions purchased from shops; each potion raises a specific stat by a random number. No amount of actual battling will make a human stronger, it’s all about chugging those magic potions. While this means players who have enough cash can easily max out their human’s stats, it can be tough at the beginning of the game when you don’t have much money to spare, leaving your poor human vulnerable to being quickly devoured by a zombie or melted by a robot.

*The races of The Final Fantasy Legend; concept art from the Japanese strategy guide.

*The races of The Final Fantasy Legend; concept art from the Japanese strategy guide.

The human system of progression is reminiscent of modern life, as it can be interpreted as a commentary on first world capitalism, although this comparison was probably unintended. After all, If you’re born into wealth, you have a leg up on those who aren’t, with access to private schools and pricey sports programs, your soccer mommy truly does love you and is willing to spend spend spend to give you an advantage over the other kids.

Mutants follow the progression system laid out in Final Fantasy II; their actions in battle determine their stat increases. Attacking frequently will boost their strength, while taking hits or winning battles will increase their HP. However, the mechanics that govern mutant skill growth are an unknowable system. The documentation is limited, and it doesn’t seem to behave as it should. Consequently, mutants skill up very quickly, almost too quickly, making them a potent force in your party from the very beginning.

Mutants aren’t just quick learners, they also excel in everything else, especially magic, which makes them a go-to choice for dealing group-wide damage. The catch is that the magic learning process is another unknowable system in a game full of unknowable systems. Instead of relying on spell books like humans, mutants have a “chance” to learn a new spell after every battle, but since there are a limited number of spell slots, any new spell they learn will overwrite an existing one; similar to a genetic mutation, hence the name “mutant.”

At times, mutants may possess powerful spells like Thunder, but in the next moment, those same spells may have mutated into a useless spell that quite literally does nothing. Sometimes, spells can even transform into passive abilities that only appear on the status page, randomly leaving a blank space in the battle menu where a powerful spell once was. Furthermore, as spells consume inventory space, mutants can only carry a limited number of items at a time, meaning they must carefully select which items to bring into battle. These are their only true drawbacks; however, their rapid stat progression and ability to use spells at all more than make up for any inconveniences. Mutants are easily the most powerful race in the game, by virtue of being unbalanced, and as such a good strategy for steamrolling the entire game is picking four mutants to start with.

*Source: The Final Fantasy Legend English manual, circa 1990; observe the “Americanization” of the concept art in all its cringey glory.

*Source: The Final Fantasy Legend English manual, circa 1990; observe the “Americanization” of the concept art in all its cringey glory.

Monsters are the third playable race and as the name implies … they’re monsters. They mirror the monsters you encounter throughout your journey, except they’re friendly. Monsters boast the most peculiar progression system of all, a system that may as well be called cannibalism; defeating other monsters in battle yields their meat which your monster can then consume to morph into a (seemingly) random new monster. As such, the core of their progression system is simply morphing into stronger monsters; similar to Pokemon’s evolution system, but not really, because the underlying mechanics that govern these evolutions are another unknowable system unexplained in the game or its manual.

The morphing system is as enigmatic as the mutant skill up rates. Like one of those scammy mystery box subscription services, you never know what you’re going to get, but it’s surely less than what you paid for. After eating meat, your monster could end up significantly more powerful or, conversely, something like a worm that only knows how to wiggle around. Thankfully, consuming boss meat consistently results in a substantial upgrade, but in terms of stat progression, monsters never keep pace with mutants or even humans. For the most part, they’re dead weight, but if you’re fortunate enough to have a monster morph into a healer, you can keep them in your party as consistent support; or you can just not recruit monsters, which is probably the best option.

Another issue with monsters is their inability to carry items or use weapons and armor, which is crucial since items play a critical role in general combat and overall survival. Since there are no inherent special attacks outside of magic and a few monster abilities, weapons are your primary source of damage; varying wildly while adding to the series’ genre-blending aesthetic, you’ll find futuristic laser swords, nuclear bombs, and submachine guns alongside classic iron swords, bows, and axes. Like most role-playing games, there are traditional medicinal items such as potions, remedies, and elixirs, all of which are pivotal in keeping your party healthy during long Tower climbs. As such, a character who can’t use even the most basic of items is a liability.

Each character has eight inventory slots for spells, weapons, armor, and consumable items. While the player’s bag can only hold about twenty items. This makes battling with inventory space as frequent as random encounters. Furthermore, weapons have a limited number of uses before they break, which is similar to the weapon degradation system in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild; however, SaGa was doing this before it was cool (and by “cool” I actually mean “widely hated”). This weapon degradation system necessitates stocking up on weapons before leaving town, which adds to the already existing inventory management struggles.

*Mutant (ARTH) and monster (VERO) inventory and stats compared; end-game. Note the large difference in stats; also note the numbers next to XCLBR, indicating how many uses the item has left.

*Mutant (ARTH) and monster (VERO) inventory and stats compared; end-game. Note the large difference in stats; also note the numbers next to XCLBR, indicating how many uses the item has left.

In typical role-playing fashion, a hero’s fate in battle is determined by their HP, dying if their health is depleted. The dead can be revived in town, but there is a unique twist to the standard formula here with the introduction of permadeath. Each hero in the game has three hearts, in addition to their HP, and when they die in battle, their heart count decreases by one. If a hero loses all their hearts, they die permanently and cannot be revived. Since enemies tend to target the party leader before other characters, your initial hero, like all other heroes, is not immune to this mechanic and is likely to be the first to succumb to permadeath if you’re not careful.

This heart system can be seen as a precursor to the LP (life point) system introduced in later SaGa games, where LP serves a similar purpose to hearts; however, not all SaGa games have permadeath, most just force a game over if your main protagonist runs out of LP. In this way, The Final Fantasy Legend is far more punishing than later games in the SaGa series.

Fortunately for your heroes, the game offers several ways to mitigate permadeath. The first option is obvious: save scumming. If your characters die, simply reload a previous save. This method, while valid, always feels cheap to use, like you’re circumventing core game mechanics by using a technicality; I don’t like doing it but I do it regardless; cognitive dissonance be damned. The second option is to purchase hearts from shops, though this is not viable early on since you will be constantly low on funds. However, as you progress through the game, battles start rewarding large sums of money, making it less of an issue; so if a character dies, just buy them a new heart – If only it was that easy in real life! As a last resort, you can recruit additional heroes from town guilds, which is useful in the event of permadeath; however, new recruits need to be trained entirely from scratch, making this final method a huge time sink.

Expanding on the save scumming, The Final Fantasy Legend features a generous “save anywhere” system that ends up being a double-edged sword. While it allows you to save progress at any time, this is not always advisable since certain areas can be difficult to escape from, especially if you only have one hero alive and very little health left. This, combined with the fact there is only one save slot, can and will result in nightmare scenarios where you become “trapped” without a previous “safe save” to revert back to; feverishly forced to reload your bad save over and over until you miraculously make it back to town to heal up; something that happened to me more than once.

The final boss area is a prime example of this nightmare in action, with no option to return back to town, a save here could easily result in a death sentence forcing you to restart the game entirely; making the true final boss the Savestate Ouroboros, Ruiner of Computer Games With Poorly Conceived Save Systems.

*A new encounter in one step!

*A new encounter in one step!

One potential solution to prevent the Savestate Ouroboros’ signature move, the Dreaded Soft Lock, is to incorporate a way to manipulate the encounter rate, which is either too low or frustratingly high with no middle ground. At the beginning of the game, the encounter rate seems low, but as you progress higher in the Tower, the encounter rate rapidly increases; in many cases, you encounter a new battle after taking just one step. An option to prevent or lower the encounter rate would help avoid getting “trapped” after a bad save decision. Another potential solution is to have more accessible teleportation options; while there are a few options allowing you to teleport back to town, they are consumable and so rare that you most likely won’t have them when you need them. Finally, there could be more than just one save slot, which would solve these issues entirely. Unfortunately, we’re stuck without these improvements, so “soft locking” your save file in a bad save situation is all too possible, so be careful.

The Pokemon series, which drew inspiration from The Final Fantasy Legend, features items which prevent encounters and early access to abilities that allow for easy teleportation back to safe zones. In their genius, GameFreak recognized a potential issue with their one save system and implemented features to prevent it early on; a step in the right direction and a direct improvement on what we have in The Final Fantasy Legend. Of course, Pokemon also includes a feature that sends you back to a safe zone when all your Pokemon die, so they’re fully immune to the Savestate Ouroboros’ attacks.

A computer game’s difficulty should not rely on getting stuck in a bad situation; this just leads to frustration and rage quitting. Instead, a game should use its gameplay systems to create fair situations that are difficult only due to player failures that can be learned from and corrected, not core system failures like a bad save system.

*Thanks for the tip, mysterious top hat man!

*Thanks for the tip, mysterious top hat man!

Gameplay systems are important, but how does the player actually progress in the game? Like most role-playing computer games from this time, progression is facilitated through the completion of quests, these quests are revealed through highly mysterious dialogue with NPCs scattered throughout each world. Discerning the exact steps needed to complete said quests can be challenging at times because the dialogue can often be vague and cryptic, such as “look for the old man” or “the king has the shield.” Fortunately, the game’s overworld is relatively straightforward, with only a few places to explore in each world; meaning that even during moments of confusion, you will quickly stumble upon something that propels the story forward, even if it’s by accident.

That being said, there are several instances where progressing isn’t as straightforward as it should be; almost as if the developers intended for you to seek help outside of the game by consulting with a tip line or a knowledgeable friend who already beat the game. For example, there is a quest where you must solve a riddle that goes something like “what is three long swords and a gold helmet?” The objective is to obtain the item being referred to in the riddle. While not immediately obvious, you are supposed to calculate the total price of each item, find an item that is sold for the same amount, and then bring that item to the riddler to obtain the reward. Some may say this type of computer-game-crypticism adds charm, but I find it simply shows how old fashioned The Final Fantasy Legend is when it comes to game progression. Yes, the game was made in 1989, so it’s understandable to an extent. However, there is a point where cryptic nonsense negatively impacts any game regardless of age. Thankfully, moments of extreme crypticism only happen twice (that I counted), so it’s not a huge issue, especially in the internet age when you can just look it up.

And in case you’re wondering, the answer to that riddle is “Battle Sword.”

Conclusion or: Reaching the Top of the Tower

The Final Fantasy Legend, known for its unusual character progression and genre-hopping science fiction setting, serves as the perfect blueprint for future SaGa titles. With its brooding post-apocalyptic atmosphere and strange creatures that seem to have crawled out of a horror movie, playing the game is like stepping into an 80s dark fantasy or otherworldly dreamscape; similar to reading a Vampire Hunter D novel (minus all the vampires and misogyny). The score, composed by Nobuo Uematsu, perfectly complements the setting despite the limitations of the Game Boy sound chip; and the graphics somehow do a great job facilitating the imagination to build upon its green-tinted world.

Although The Final Fantasy Legend offers solid gameplay, some players may find the confusing systems and simplistic graphics unappealing after being spoiled by modern computer games; while playing games of this nature comes naturally to those born in the 80s or 90s, others may find it too outdated to enjoy. This is OK, as many older games are simply not worth playing outside of partaking in nostalgia or contrarianism, observing historical significance, or attempting to bolster your self-esteem by seeking attention and validation online by bragging about all the cool old games you play (something I may or may not be guilty of; this author prefers to leave that open to reader interpretation).

*Congratulations! You have reached the top of the Tower! Thank you for reading!

*Congratulations! You have reached the top of the Tower! Thank you for reading!

The Final Fantasy Legend is not a game that falls under the category of “not worth playing”, but it is not necessarily a “must play” title either. Games from the same time period, such as Dragon Quest III and Final Fantasy II, featuring comparable turn-based combat and character progression systems, did the same things and arguably did them better; however, neither of these games match the level of quirky originality found in the first SaGa game.

Clocking in at about 5 hours to complete, it doesn’t hurt to give The Final Fantasy Legend a try, especially if you’re interested in the origins of the SaGa series or just want to experience the first ever role-playing game for the Game Boy. Love it or hate it, you’re not wasting much time either way.

As always, if you get bored. Put the controller down and do something else. If you’re not having fun, it’s not worth it.

(originally published on 5/14/2023)