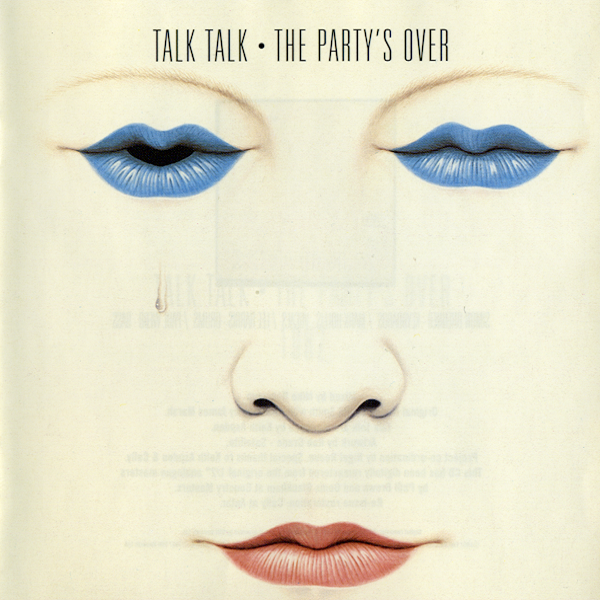

The Party’s Over (1982), Talk Talk

The now defunct British music newspaper Record Mirror asked Mark Hollis, principal singer-songwriter of the band Talk Talk, in 1982 what his greatest ambition was; Mark’s response was “owning a car.” When asked about his greatest heroes, he said “mum and dad.” His top musical influence was “Burt Bacharach,” and his favorite film was “A Clockwork Orange.” His ideal holiday was “New York,” and his favorite drink was “Gin.”

When asked about his first love, Mark Hollis gave the nickname of his childhood sweetheart: “Flick.” He would go on to marry and have two children with Flick, living with her for the rest of his life.

Reading the 1982 Record Mirror profile of Mark Hollis, one gets the impression that he was an everyman; someone who never intended to be a pop star, someone with the humility (or wisdom) to stay out of the spotlight. He longed for a peaceful life, a slow fade into a pastoral backdrop, with down-to-Earth hopes and dreams; so it’s not surprising that when asked about his ‘ultimate dream,’ Mark Hollis replied, “drinking gin in my Aston Martin DB6 around New York,” or: a criminally good time.

Mark Hollis’ father had a different dream, a failed dream, that of becoming a famous musician; some fathers’ failures are so potent they simply cannot fade into the pastoral backdrop; they must be inherited by the children; the dream must live on for as long as it takes to manifest in the physical plane.

This was reality for young Mark Hollis: his father, an unsuccessful musician, insisted that both Mark and his older brother, Ed, pursue music above all else. Influenced by his father, Mark learned to play both piano and guitar at a young age but never felt confident in his musical ability and despite his father’s dreams, in 1975, Mark chose to pursue Child Psychology at the University of Sussex.

The love of music instilled by his father never faded, and confidence can be a tricky beast; often, an outward appearance of confidence, regardless of the trembling-inside, can be enough to trick others into believing you’re the real deal; this is the case for charlatans and businessmen, which are (more often than not) synonymous; however, this confidence trick is much harder for artists, as perfectionism runs deep in the artistic mind and you can’t fake a beautiful painting or a hit song; fortunately, confidence can come from the most unsuspecting of places, and in Mark Hollis’ case: morons who couldn’t play instruments and sang about anarchy while being signed to a major record label – the Sex Pistols.

The classic motivation of, “if those idiots can do it, then so can I.”

By punk, I am convinced that musical technique is of minor importance. My feeling is that the strength, the zest in music is much more important. In fact the most important. That’s why I felt attracted to punk. –Mark Hollis, Oor Interview, April 1986

Inspired by the Pistols, Mark Hollis formed his own band, The Reaction, and collaborated with his older brother Ed Hollis to write and record a short two-minute song titled ‘Talk Talk Talk Talk.’ A song about the double-speak of officials and the chess-like courtship rituals of Words Don’t Mean What You Think They Mean. In his signature trembling voice, Mark Hollis explodes, “All you do to me is talk, talk!” Embodying the spirit of the everyman who desires only to return to a simpler time; a core tennant of minimalism found throughout all of Mark Hollis’ work.

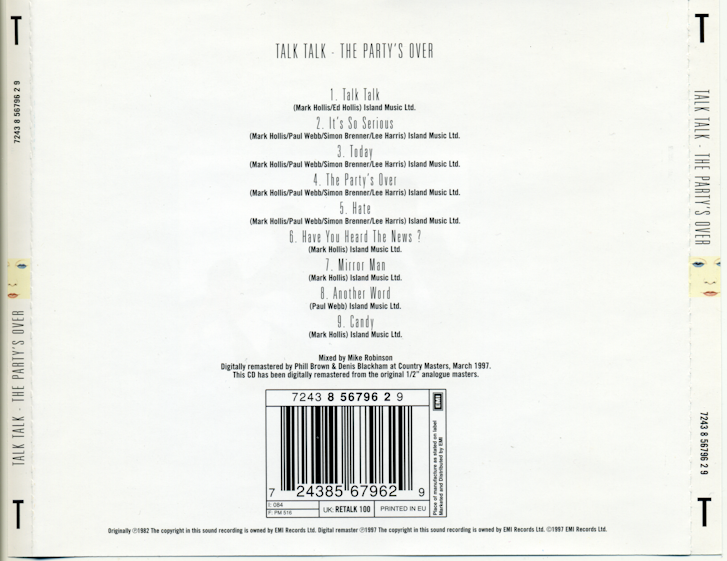

Mark’s brother and early collaborator, Ed Hollis, was already a manager of a semi-well-known pub-rock band, and had connections within the local London music scene, allowing him to put Mark in contact with Lee Harris, Paul Webb, and Simon Brenner, responsible for drums, bass, and keyboards, respectively. ‘Talk Talk Talk Talk’ underwent a synth-inspired reworking for the post-punk era, losing two ‘talks’ in the process and metamorphosing into ‘Talk Talk.’ After another hook-up from Mark’s brother, a demo was recorded in Island Records studios and eventually the song was sent to EMI, leading to Talk Talk’s signing for a record deal in 1981.

Thus, Talk Talk was born and Father Hollis’ dream was closer to becoming reality.

*Talk Talk 1982; ”The Party’s Over” record insert: Simon Brenner, Lee Harris, Paul Webb, Mark Hollis (respectively)

*Talk Talk 1982; ”The Party’s Over” record insert: Simon Brenner, Lee Harris, Paul Webb, Mark Hollis (respectively)

From the very beginning, Mark Hollis wanted Talk Talk to be something different from his radio-friendly contemporaries, specifically Duran Duran and other ‘New Romantic’ bands of the early ‘80s. But this wish was self-sabotaged by being on the same label as Duran Duran (EMI), having their first record produced by Colin Thurston (the same producer for Duran Duran), a band name of a word repeated, and going on tour as Duran Duran’s opening band in 1982 for exposure; possibly cementing the public’s view of Talk Talk as another Duran Duran, but one look at the band members and, most importantly, one listen to Talk Talk’s music says otherwise.

“Our songs are about tragedy… human tragedy; like the title track, The Party’s Over, that’s about someone who’s past their prime and won’t actually acknowledge the fact. They’re striving for what they used to be and looking ridiculous. It’s just the conflict between trying to attain something more than you are, which is a good thing, and the parody of actually doing it. It’s just an observation. Tragedy’s what I feel most at home with.” – Mark Hollis, Record Mirror, 5/8/1982

Talk Talk in 1982 is Duran Duran without the makeup, hair dye, lust for attention, silly headbands, fraudulent air of nobility, and pretty much everything else that makes Duran, well, Duran; and while “The Party’s Over” may start with a shimmering synth line reminiscent of something from Duran Duran’s 1981 album “Rio,” once Mark Hollis starts singing, it immediately becomes apparent that we’re in for a darker and far less superficial experience.

‘Talk Talk’ starts with a pounding drum fill, basslines that sound like plucking rubberbands stretched between two fingers with as much slack as possible, and two layers of synthesizers: a lead synth resembling the melody of a twisted children’s carousel and a second computer game bounce that Sega likely borrowed for their 1988 Megadrive soundchip, all dominating the mix before Mark Hollis’ distinct vocals take charge. Here, Hollis sounds angrier than he will for the remainder of the album, with his voice trembling and seemingly on the verge of bursting into a fit of rage before calming down a bit in the subsequent track ‘It’s so Serious’ — very much a sister-song of swirling synths and cynical yet vulnerable subject matter.

Some tracks are driven solely by Paul Webb’s rubberband basslines and Lee Harris’ energetic industrial drumming while Mark’s vocals haunt the mix before bursting with synthesizer splendor only during the chorus, as evidenced in the standout ‘Today,’ the album’s strongest single, partially propelled by a chanting of the title and Hollis’ ghostly vocals naturally echoing through the valleys of his own emotional caterwauling. This organically leads into ‘The Party’s Over,’ which drops subtle hints as to the direction of Talk Talk’s later work with its minimal soundscapes driven by simple yet subdued synths and a lazily-captivating bassline that builds to a moody tsunami of a chorus before returning to calmer yet now forever rippling waters.

‘Candy’ serves as the thematic and literal finale to both the album and its titular track; a successor song incorporating Father Hollis’ and Burt Bacharach’s influences by layering a minimal-piano-pop nocturne in lockstep with the odd drum timings and that ghostly-wail of a vocal line, something later Talk Talk albums expand upon considerably. On both ‘Candy’ and ‘The Party’s Over,’ easily the album’s strongest tracks, Mark Hollis’ haunting vocals are used to full effect, showcasing his impressively loud range; constantly quavering on the verge of tears, of either sorrow or joy quizzically, echoing upon itself into a spectral wall of sound that effortlessly blends into the surrounding doomed landscapes; this effect draws some similarities to Talk Talk’s distant contemporaries, the Cocteau Twins, where Elizabeth Fraser’s vocals serve less to communicate lyrical content and more as an additional instrument within the arrangement.

While unique and full of promise, Talk Talk’s “The Party’s Over” is a mixed bag: very much a synthpop record with simple song structures, with the first-half’s blatant pop bleeding into the second-half’s moody atmospherics that are just accessible enough not to be entirely off-putting to an audience clearly intended to be Duran Duran fans. Singles such as the self-referential ‘Talk Talk’ became brief dance-club favorites, and the music video played on MTV in its infancy; the latter being a practice Mark Hollis would go on to protest in his iconic music video for ‘It’s My Life,’ rebelliously composed of only stock animal footage and brief shots of the singer with a censorship bar over his mouth. Based on Mark Hollis’ later work, it’s easy to come to the conclusion that “The Party’s Over” was not a natural extension of himself, but rather a product of the time and, more specifically, EMI’s commercial sensibilities, with only sparse pieces of Mark Hollis’ true-self inserted whenever he could get away with it.

In Mark Hollis’ own words, “It’s just the conflict between trying to attain something more than you are, which is a good thing, and the parody of actually doing it.”

“The Party’s Over” is the parody of actually doing it; a time capsule of a band in it’s formative years. An album easily surpassed by their next album, which, in turn, was easily surpassed by the album after that, and again after that, forming a cyclical epic leading to the eventual creation of two genre-defining albums: “Spirit of Eden” and “Laughing Stock,” which led to a wave of imitators that could never quite reach Mark Hollis’ level of genuine, down-to-Earth brilliance – but that’s a story for another four articles.

What matters here is that Father Hollis’ dream had come true: his boy had made it, and the party had just started.

(Provided my attention span holds (it won’t), this is likely the first in a series of articles about each Talk Talk album with a focus on telling the story of Talk Talk and Mark Hollis. I like Talk Talk a lot, so of course, it’s all biased all the way down. And it will likely be awhile before I write another entry, as it took far more research than my more simple opinion pieces; the bits about Mark Hollis’ father are shaky at best as they’re solely based on information in one article. Conclusion: I’m sure I got something wrong somewhere. The gist of the story, however, is correct, and like all history: the game of telephone facilitates the creation of legends. Special thanks to Snow in Berlin, an excellent Talk Talk fansite that cataloged seemingly every Talk Talk interview ever, from which all the quotes and historical stories are pulled from.)