I, The Fog of Youth

In an alternate universe far far away and a relative time long long ago: The Boy.

The Boy came home from elementary school one day and The Dad was crying on the fuzzy tan couch – the first time The Dad cried in front of The Boy. The Boy’s parents were getting divorced, but The Boy didn’t care as long as it didn’t interrupt his Nintendo 64 time; ignorance was bliss for The Boy until the consequences kicked-in.

After that fateful day, The Boy would forevermore go back and forth from The Mom’s house and The Dad’s house, every month, without fail, like clockwork.

At the end of every month, on the 30th, 31st, or maybe 28th or 29th, one of the parents would drive The Boy to the other parent’s house. That parent would kiss The Boy on the head and usher him out of the car without saying a single word to the other parent.

“I’ll see you in a month; I love you,” were the cries of nuclear absenteeism, and those split custody blues.

That alternate universe was Earth, Milky Way Galaxy, the arm of Orion; and that relative time was 2001.

The Boy’s mom had quickly remarried, and The Boy suddenly had a second dad. This dad was The Mom’s old work boss – a fact discovered 10 years later – and the two had been seeing each other far longer than The Mom had been divorced. Implications of infidelity whispered within the family. But, none of that mattered to the youngling who just wanted to play computer games and stay up late on school-nights watching Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim without getting in trouble.

This second dad – The Step Dad – had an odd parenting philosophy; either due to laziness or genuine misguidedness, he believed money was love and would buy The Boy anything to win his affection. And by “win his affection,” what the author really means is “leave him alone” because The Step Dad had better things to do.

Naturally, The Step Dad empowered The Mom to buy The Boy whatever The Boy wanted; one of the first things purchased for The Boy was an iMac G3 in “Bondi Blue” color, an extremely aesthetic piece of hardware that combined monitor and guts into one fat transparent unit, capable of playing a number of educational point-and-click computer games made for young children, including Pajama Sam: No Need To Hide When It’s Dark Outside and Blues Clues: Blue’s Birthday Adventure; both of which The Boy played extensively, along with KidPix – Apple’s adolescent MS Paint with more soul than features.

With this powerful machine came unfettered access to dial-up internet. The Boy quickly learned the magicks of instant messengers, particularly AOL Instant Messenger, and discovered how to access online gaming and anime forums. More than once, The Boy gave his home phone number to the wrong anonymous man online, whom The Boy innocently thought just wanted to know his age.

All was fun and games until one of these anonymous men showed up at The Boy’s house and was promptly arrested when The Step Dad happened to – miraculously – be home to call the police.

The Boy quickly learned to fear those who hid their face online but, as a consequence of his own actions, started hiding his own face online; fear and hypocrisy within the fog of youth.

The Mom and The Step Dad, after this stressful event with The-Man-Who-Just-Wanted-to-Know-How-Old-The-Boy-Was, gave The Boy the cautionary words of the world wide web: “it’s dangerous and there are weird people on those sites,” and with that The Boy had learned his lesson – or, at least, the two misguided parents believed he did and erased the whole incident from their minds.

*digital landscape of The Boy circa 2001, authors: unknown

*digital landscape of The Boy circa 2001, authors: unknown

The Boy grew up in the world-wide-wild-west of anything-goes and inconsequentials.

Unrestrained by caution, The Mom lavished The Boy with any coveted electronic game he asked for, oblivious to the parental scrutiny needed to weed out corrupting influences. Consequently, a trove of mature-rated Nintendo 64 and PlayStation games amassed in the boy’s possession, a cache ill-fitting for his youthful 11 years. Foremost among them reigned Duke Nukem 64, a title that cast The Boy into an abyss of terror, ensnared by its chilling portrayals of crimson blood, intestine gore, and brain-bulbousing extraterrestrial beings lurking around every corner – and the underwater sharks, stalking the waters of every lake, sea, pond, and fountain; the latter of which The Boy never bothered to question.

How did sharks get into the fountain?

Duke Nukem 64 would go on to cultivate the fear; the fear of things lurking within the unseen; the darkness, the murky fog of the ocean and of youth, with sharks, jellyfish, and creepy men circling The Boy’s obscured feet.

Reaffirming Jack Thompson’s fears, The Duke introduced The Boy to sexuality; voluptuous scantily-clad women sprinkled throughout the violence, often trapped in alien-green-goo; moaning and begging Duke for release – incredible, in hindsight, that Nintendo allowed this game on their console, as it did exactly what Nintendo so famously fights against: corrupting youth.

In between computer games, iMacs and the internet, The Boy would – like any other child – go to school, an endeavor The Boy vehemently hated. Luckily, The Step Dad lavished The Boy’s sister with a brand new BMW; expensive German motorcar, jewel of the neighborhood. The Big Sister frequently chauffeured The Boy to school in this big-beautiful-overcompensator, as The Mom and The Step Dad were far too ensnared in the clutches of work – or traveling on their expensive yacht – to find time to dedicate to The Boy.

The Big Sister’s expensive car overflowed with rap CDs; initially, the boy was drawn to them, fascinated by the profanities only allowed by adults on television. One album that held his particular favor was Outkast’s “Stankonia,” despite its CD art portraying a deceased man skewered on a spike, an image that instilled in him an enduring fear, an image that could be seen when he closed his eyes to go to bed.

Much too late, in adulthood, The Boy would come to realize that the Stankonia artwork depicted a horned woman colored in psychedelic orange-and-black, perhaps a succubus, rather than a dead man – but, regardless, the image was still frightening to the then-11-year-old.

The Big Sister’s musical preferences imprinted themselves upon The Boy, at least they did early on – before The Darkness and The Cool crept in.

And The Darkness and The Cool came quickly. The Boy cultivated the seeds of his future aesthetic preferences during the months spent in the wild-west of his mother’s custody; a free-for-all of anything goes where he was free to discover his own darkness and pursue his own cool without interruption, most of which consisted of bad influences and moving pictures.

Eventually, the boy would grow out of his sister’s musical tastes, introduced to bands such as The Cure and The Smashing Pumpkins one summer due to the influence of older neighborhood kids; kids who seemed to not have a care in the world other than getting into trouble and smoking cigarettes – something the boy also wanted to do but was too timid, afraid of word getting back to The Dad.

The Everlasting Gaze – The Dad.

So, instead of getting into trouble directly, the boy obsessed over music and dreamed of being a pop star – not of the Madonna variety, but the detached-frontman-with-cool-hair variety. Quickly falling in love with The Cure’s “Disintegration” and The Smashing Pumpkins’ “Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness”.

The concepts of The Darkness and The Cool – something The Boy knew nothing about, but he didn’t know that at the time.

In 2001, The Darkness was cool, and The Boy wanted to be empty; emptiness is cleanliness and cleanliness is godliness – and God is empty, just like The Boy who wanted to be Billy Corgan’s Zero.

At least that’s what the boy thought; he wanted to be empty, but at the same time, he wanted Mom to keep serving him chocolate milk with the bendy straw in the Power Rangers cup every morning while he watched Nick Jr.

Nick Jr. and Blues Clues. Little Bear, and Gully Gully’s Island.

The Boy, growing up so fast, could never let go of childlike whimsy. To the point where he was playing Blues Clues: Blue’s Birthday Adventure on iMac one day when his older and “cooler” friend came over. The Boy quickly turned off the iMac when the friend entered the room, but The Boy had forgotten to hide the game’s box. The Friend saw the box, picked it up, looked at it closely and laughed; then took his necklace off – a thick metal chain – and proceeded to beat The Boy with it.

Fear. The Boy would be careful about expressing his true interests from now on.

And for reasons The Boy will never be able to fully articulate: The Boy and The Friend stayed close for years afterwards.

Suburban Stockholm syndrome.

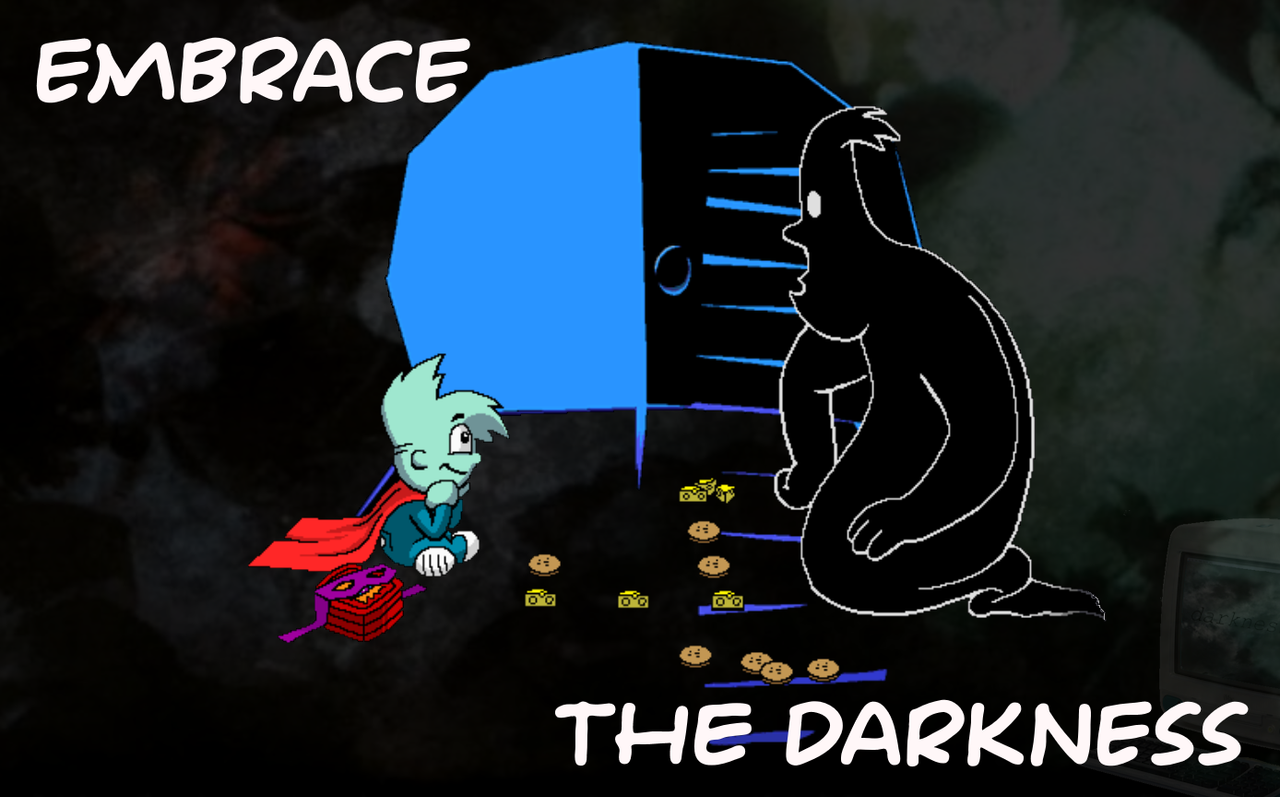

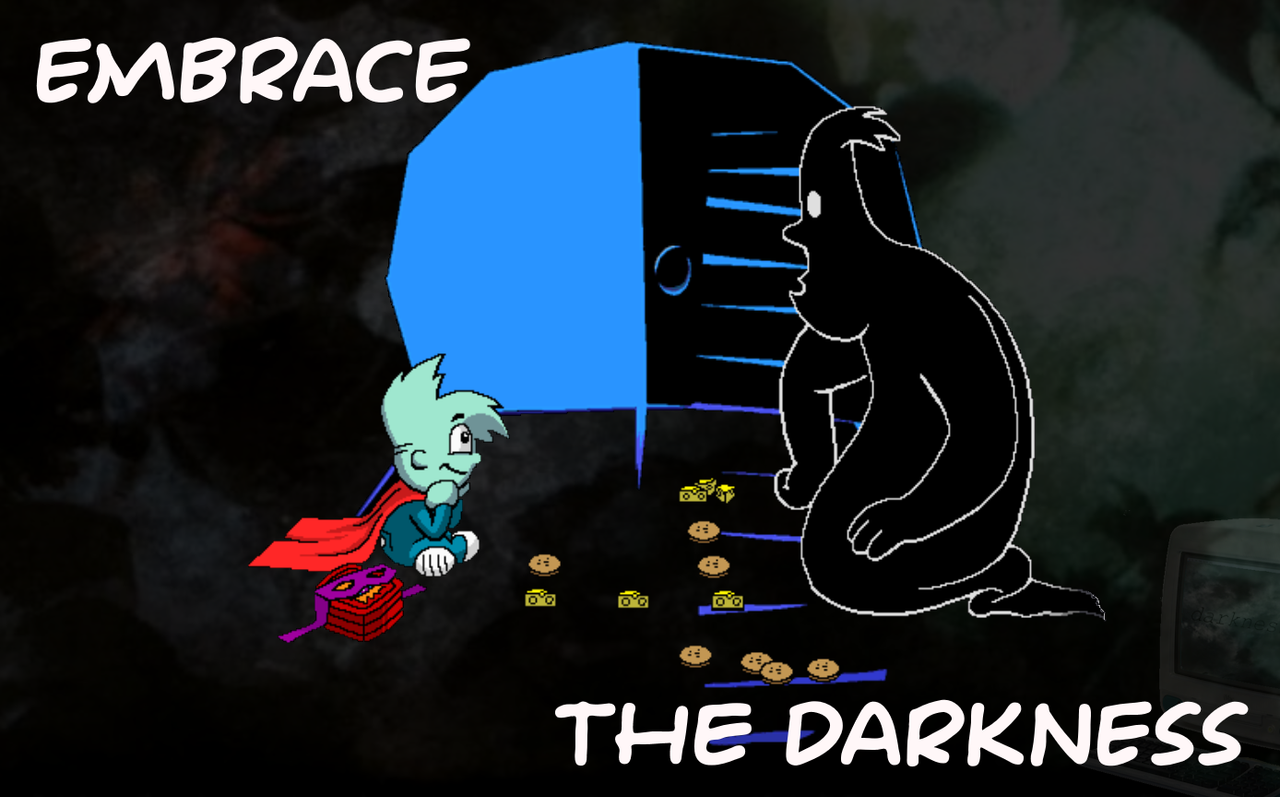

*The Darkness we know so well; stepping through the fog of youth

*The Darkness we know so well; stepping through the fog of youth

The Boy wanted to emulate the uncaring future dropouts, who possessed more privilege than they knew what to do with, and he desired to be loved in the process; to become one of those cool kids who feigned poverty despite dwelling in expansive three-story mansions, discarding more food nightly than an average denizen of the third world consumes in a month.

In pursuit of this contradictory facade of apathy and destitution, at the age of 12, The Boy embarked on a quest to procure several pairs of overpriced baggy tripp pants – the kind adorned with hanging belts – from the local goth store at the mall, while adopting an all-black attire.

The Boy thought this made him one with The Darkness.

The Faux-Darkness enshrouded The Boy. The Mom found it peculiar but exhibited minimal concern; she did buy those pants for him, after all, and subscribed to the notion that “he’ll grow out of it soon,” a concept she read in a parenting self-help book.

Indeed, The Boy did grow out of it, albeit not immediately. Soon after his dalliance with The Darkness, he crossed paths with The Girl who too had experienced The Darkness, and they became inseparable – a narrative best left for another time.

The Girl or not, The Mom’s offerings of material affection persisted unabated; troves of electronic games, Gundam models, Dragon Ball figurines, and other plastics destined for the landfill flowed like the legendary waters of the fountain of youth; this little “gothic” 12-year-old boy reveled in a state of euphoria every other month.

Every other month.

Because every other month, The Boy hid The Darkness, put up the tripp pants, and returned to The Dad’s house.

The Dad’s house was an entirely separate universe with its own planets, stars, and laws of physics. The Dad was a stern disciplinarian: a no-nonsense real estate agent with a strict set of house rules, chores, and hang-ups; all of which needed to be fulfilled before any fun could be had.

Absolutely no tripp pants or accompanying band t-shirts were allowed.

This created a disharmony within The Boy who felt his true self – however misguided and artificial – was being forcefully repressed, and the resentment built up like dead leaves in the backyard. The same backyard The Dad made The Boy rake every other week.

Adding to resentful repression; contrary to playing computer games constantly, The Dad made The Boy play sports: baseball, basketball, and tennis at the local church; activities The Boy never wanted and had shown no interest in. The Dad, in his vain attempts to make his boy active, was living vicariously through The Boy, or his idealized version of The Boy – a fact all too obvious when The Dad would become far-too-angry when the kid’s-basketball-referee made a bad call, or when The Boy missed a baseball pop-fly because he was lost in his thoughts, pondering on the The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time.

The dead leaves continued to build.

The Dad didn’t like to spend money on The Boy; not poor, but frugal, and The Dad aimed to teach The Boy the lessons of frugality. The Boy, so used to love being expressed through material means, felt that The Dad didn’t care about him due to the lack of brand-new things.

The Dad was stubborn and refused to buy The Boy new things, unless The Boy worked hard for it.

“Working to earn something is more rewarding than getting it without any effort – you will appreciate it more if you buy it with your own hard-earned money,” The Dad would often say.

The Dad loved his son and wanted him to grow up to be a responsible man, perhaps even a better man than himself.

It was obvious to any onlooker. It was not obvious to The Boy – it never is, is it?

And, of course, The Boy hated everything about living with his father.

The Boy would count the days until The Mom picked him up, and when he was at The Mom’s house he would – in anxious dread – involuntarily count the days until he had to return to Hell.

When in Hell, The Boy would get home from school and immediately go upstairs to play Nintendo 64, only for The Dad to take him by the hand, sit him down at the kitchen table, and tell him to complete all his homework first.

Stubborn but too passive to vocalize it, The Boy would sit at the kitchen table until dark – sometimes until bedtime – putting in the least effort possible out of spite, getting no homework done; not realizing that simply doing the work would enable him to spend more time doing whatever it is he wanted to do.

And when bedtime came around, The Boy would play Game Boy under the covers – sneakily killing the lights whenever he heard footsteps to avoid The Dad and The Step Mom from catching him staying up far past his bedtime.

Dad would often wonder why it was so hard for The Boy to get out of bed in the morning.

*ghosts of the past haunt The Boy overlooking suburban splendor

*ghosts of the past haunt The Boy overlooking suburban splendor

The Dad’s house helped The Boy learn how to be subtle – how to repress his feelings. But it also taught him structure and discipline. In a roundabout way, The Dad was a role model; initially resented but ultimately redeemed, like The Smashing Pumpkins’ album “Adore.”

From an outsider perspective, and from The Boy’s future adult-perspective, this custody-tug-of-war was a necessary evil – The Mom and The Dad, back and forth.

The Boy’s parents may have been divorced, but they exerted the same level of balance on The Boy’s life; albeit in monthly increments of extreme bliss and extreme – perceived – torture.

And without a hint of sarcasm, The Boy had an incredibly privileged life.

Going on thirteen years of age The Boy continued to play the childish computer games The Mom bought him for that old iMac G3 – a late bloomer; the games The Friend violently disapproved of.

The Boy’s favorite childish computer game was Pajama Sam: No Need to Hide When It’s Dark Outside.

That game was about a young boy named Sam: his aspirations, his hopes, his dreams, and overcoming his fears.

But most importantly, that game was about The Darkness.

II, Embracing the Darkness

Sam is a boy obsessed – a boy obsessed with a comic book hero. Much like The Boy obsessed with pop stars, computer game heroes, and The Darkness; something only captured in the brief fleeting moments of dancing in front of a mirror alone.

But, unlike The Boy, Sam is scared of The Darkness, as any child should be; Sam doesn’t want to drape himself in The Darkness; he wants to rid himself and the world of The Darkness. And, also unlike The Boy, Sam’s obsession is in reach; every night he becomes Pajama Sam – or does he?

Sam’s goal is to destroy The Darkness, and he will do anything to achieve this goal.

The Darkness isn’t so bad until bedtime, when Sam’s mom comes into the room; a parental figure never actually seen on screen, similar to that of a Sunday morning cartoon parent, with only her hands and feet visible.

The absent Mom tells Sam to find his socks in the closet and put them in the dirty-clothes basket before going to bed, a simple task to The Mom – a dreadful task for The Boy.

Dreadful because the closet is where The Darkness resides. There’s no night-light in the closet, and when The Mom shuts the door, The Darkness starts to creep in.

Sam, so scared of The Darkness, decides to become a hero to conquer it, a hero straight from his favorite comic books: Pajama Man.

“That’s right, fiend! Pajama Man is here to conquer The Darkness,” exclaims Sam’s favorite comic book superhero in the splash screen presented at the start of this computer game.

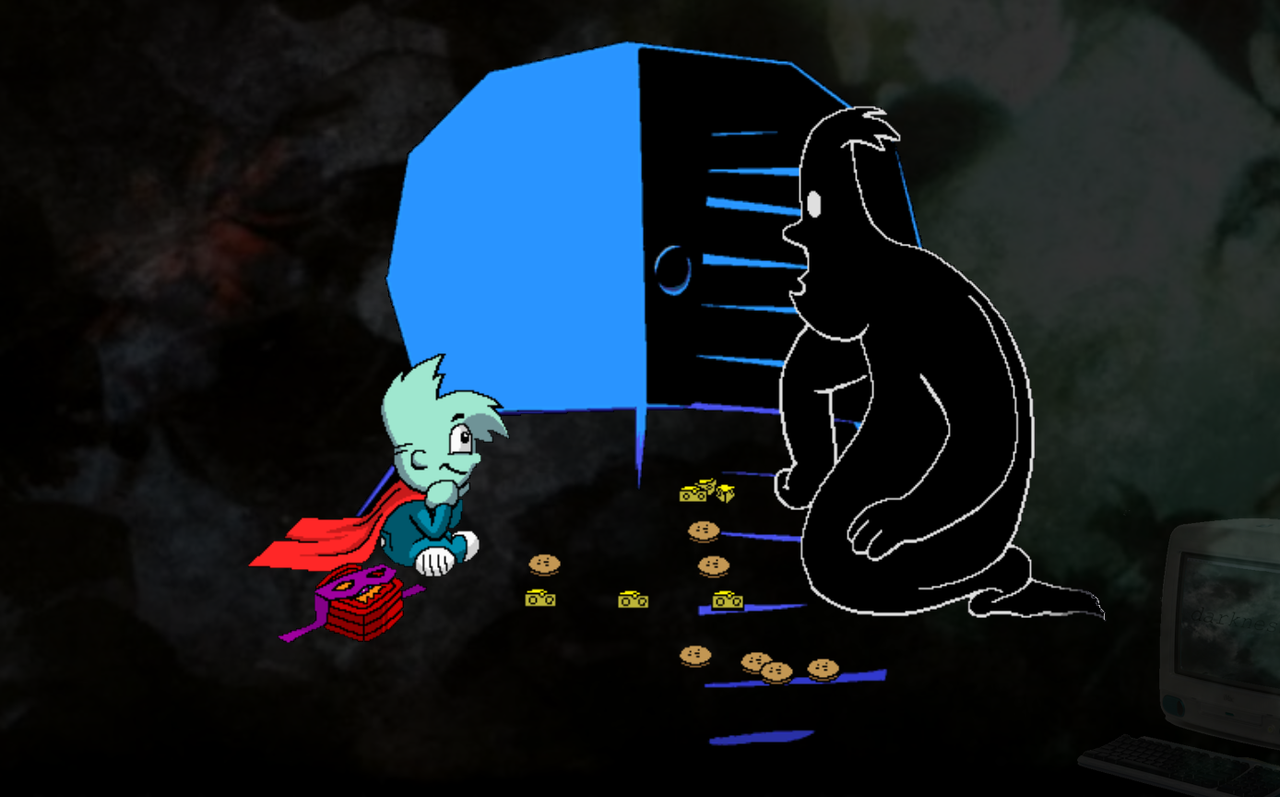

*we can be heroes, just for one day.

*we can be heroes, just for one day.

The Darkness; ruiner of daytime, bringer of bedtime.

Sam’s Pajama Man hero gear is strewn all over the room. How is he ever going to conquer The Darkness without his Pajama Man gear? Sam jumps out of bed, looks straight at the camera, and says, “I need to find my Pajama Man mask, flashlight, and Portable Darkness Containment Unit!”

Sam’s Portable Darkness Containment Unit being the Pajama Man lunch box The Mom bought for him, which he intends to use to capture The Darkness forever.

And to find these items, The Boy takes the mouse cursor and clicks on various items in the scene – in this case: Sam’s room, and everything in Sam’s room does something; his pillow, when clicked, may burst into feathers or squirt water; the coat rack in the corner of the room may turn into a stick-person and do a little dance; these are entertaining distractions for the target audience of this point-and-click computer game: 7 to 9 year-olds – not 13-year-olds, which is the age of The Boy – The Late Bloomer – who continues to play this game into his teenage years.

In a twist on the children-computer-game-point-and-clicks of the time, Pajama Sam’s adventure is different each time a new game is started; locations of items necessary for progression are randomized from playthrough to playthrough; The Boy may find Sam’s mask under the rug or on the coat rack, and the lunchbox under the bed or the nearby wastebasket, instead. This randomization applies to every aspect of the adventure, determined by the random numbers toiling around in the background before The Boy clicks the “new game” button.

And once Sam finds his mask, lunchbox, and flashlight, he too becomes like Pajama Man – the destroyer of The Darkness.

Or does he? Pajama Sam musters his courage, swings the closet doors open, takes a deep breath, turns his flashlight on, and shines it into the shadowed confines of the closet.

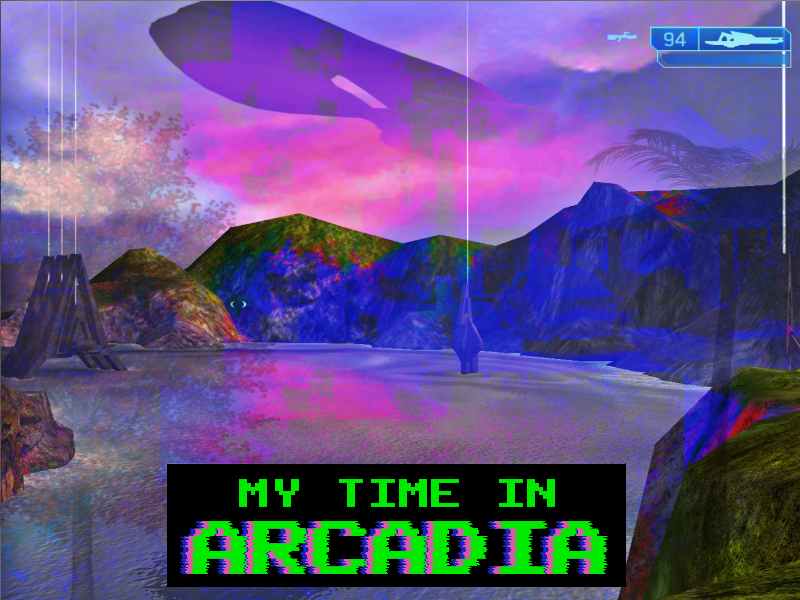

*Et in Arcadia, Pajama Sam

*Et in Arcadia, Pajama Sam

Just as Sam steps through the border between The Comfy and The Darkness, he finds himself falling through a psychedelic hole for what seems like forever. Sam’s fall is cushioned by an oversized baseball glove; a bowling-ball can be seen in the distance, along with a worn-out baseball, tennis racket, and rows of trees draped in the clothing of small children.

This is the entrance to Sam’s closet; another world where Sam’s discarded and forgotten toys, sports paraphernalia, and clothing have grown their own faces, histories, and personalities. This is a land where The Darkness dwells, in a large home – quite literally – down the road.

But Sam’s not scared; he’s got his Pajama Man mask, flashlight, and Portable Darkness Containment Unit, and he’s ready to destroy The Darkness.

Pressing on with courage and conviction, Sam travels a bridge over a stream; a suspicious plank of wood floats in the stream. Sam thinks it could be helpful, but the plank is just out of reach. A special scene plays out when The Boy clicks the stray plank, which initiates a scene showing Sam reaching out for the wood to no avail. Similar scenes play out upon clicking many things throughout The Land of Darkness, typically indicating something of importance.

Sam moves on, focused on the future, facing his fears with a mask on, into the dark woods just beyond the bridge; a forest full of large oak trees as far as the eye can see.

Filled with confidence, Sam rushes through the dark woods before realizing that something has snagged his leg: a rope.

Sam has fallen into a trap: a rope-trap tied to a tree branch lifts him into the air, leaving Sam dangling head-first in the world of upside-down.

The trap sprung within a split second, and just as he realized what was happening, he saw a large face staring at him. One of the trees – all of the trees – had faces, staring at him. Some of these trees had crazed expressions on their deformed faces, grinning from tree-ear to tree-ear in malicious pride as they had finally caught prey.

“We are customs. You are not supposed to be here,” the ringleader tree with the lazy eye and toothy smile says right before he strips Sam of his Pajama Man mask, lunchbox, and flashlight. “We, the trees, are confiscating your items,” the ringleader says with the air of an overzealous hall-monitor.

And just like that: the trees have stolen Sam’s obsessions and scattered them among The Darkness.

The Boy has returned to The Dad’s house; it’s time to put away the tripp pants, video game controllers, and goth records. Sam is just a normal boy now – no longer a superhero.

With Sam’s Pajama Man gear snatched away, he finds himself hanging alone, suspended by one leg from a rope cinched around a tree branch. The trees shut their eyes and mouths, seamlessly resuming their facade as ordinary trees, as if nothing had happened.

Sam now faces the challenge of freeing himself from this predicament.

The Boy clicks the rope.

Sam, gritting his teeth, climbs up the rope, fingers gripping coarse fibers. Slowly but surely, Sam uses his hands to ascend the rope, methodically untying the knots that hold him captive. Finally, he manages to loosen the last knot, causing him to descend with an unceremonious thud onto the ground below. The very same rope that ensnared him tumbles down alongside him; and like a scavenger in The Darkness, Sam puts it in his pocket.

Who knows – maybe it will be useful later on?

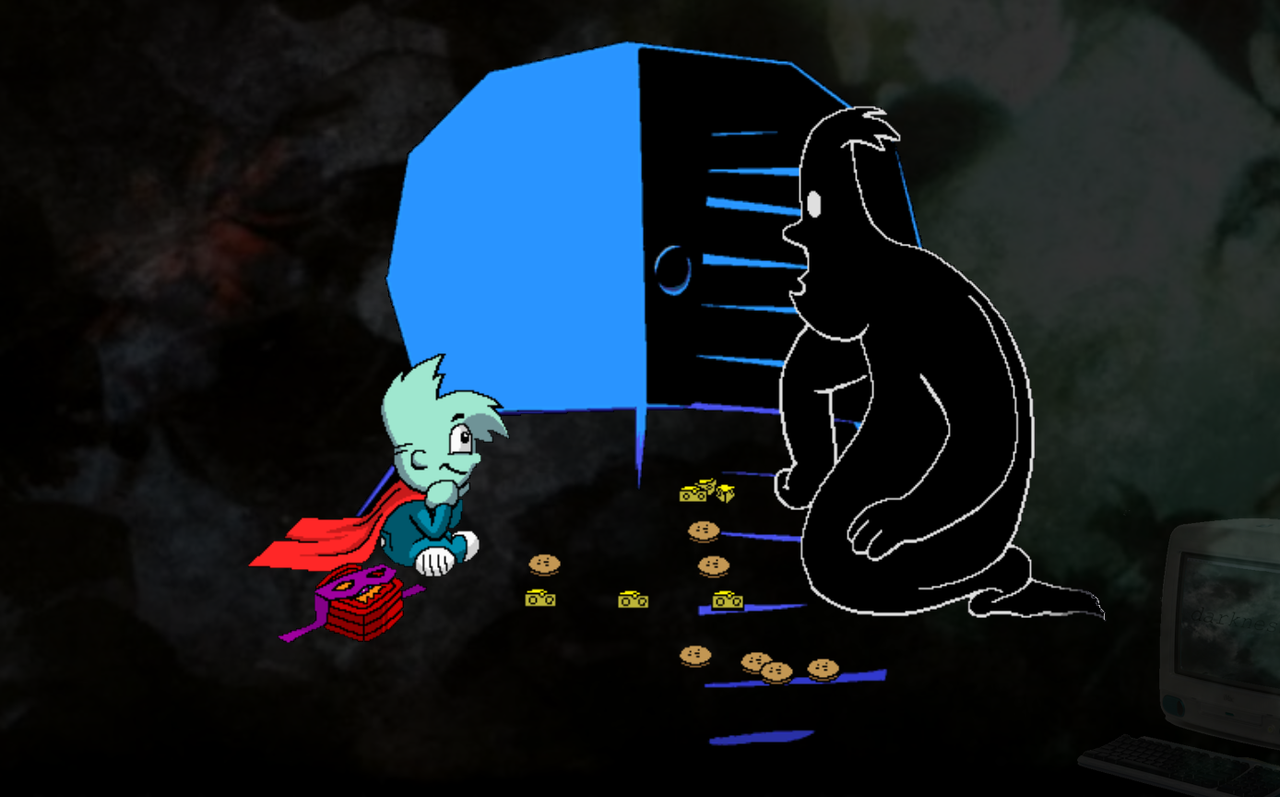

*Pajama Sam captured by the trees in The Darkness

*Pajama Sam captured by the trees in The Darkness

Before moving on, a purple tree nearby sprouts eyes and a mouth, halting Sam in his tracks. “Hey, I’m sorry about those trees; they’re not the friendliest bunch, but your belongings are still around here – somewhere. Just keep an eye out,” the tree says happily.

Sam expresses gratitude to the amiable tree and realizes his next task: retrieving his mask, flashlight, and lunchbox once more. Deja vu. After all, how can he hope to confront The Darkness within his own realm – where The Darkness is most powerful – without the Pajama Man flashlight and Portable Darkness Containment Unit?

Or perhaps this is just Sam’s closet? Regardless, Sam’s precise location holds little significance to The Boy. He forges ahead, eventually arriving at a crossroads. A colossal tree stands before him, adorned with windows and expansive tree-homes crafted around each of its sturdy branches.

A lift stationed at the tree’s base catches Sam’s eye; undoubtedly the entrance. An adjacent sign provides clear direction, labeling the path to this massive treehouse as “The Darkness’ House.”

A shiver runs down Sam’s spine, but The Boy is excited.

Confronting The Darkness without Pajama Man gear feels like an insurmountable challenge. Thus, Sam chooses the rightward crossroad marked “Boat Dock,” determined to recover his confiscated possessions which must be around here – somewhere.

At the boat dock, Sam comes across a large river. A nearby boat sits on the shore, and like many things in The Closet, this boat has a face and talks. Sam asks the boat nicely, “Can you take me across the river?” But the Boat – giving his name as “Otto” – refuses.

Otto explains that he’s scared of water, scared he might sink, scared of The Darkness – nothing will convince him otherwise.

Sam finds himself in a dilemma; how can he traverse the river if the boat refuses to get in the water? Then, a recollection strikes The Boy: the wooden plank floating in the nearby stream. With a sense of foresight, Sam recalls the rope he had used earlier, certain it could be of use once again.

“Be right back,” Sam exclaims before zipping off-screen with a sound resembling that of broken sound barriers.

Sam retraces his steps to the bridge. The Boy employs the rope with two clicks, and Sam expertly lassos the plank, drawing it out of the water and into his grasp. Sam then stashes the sizable plank within his computer-game-sized pockets.

Sam returns to Otto the Boat and tosses the wooden plank into the water nearby. “See – wood does float,” Sam says, a triumphant grin spreading across his face.

The Boy feels like a genius.

From this point on, Sam and Otto forge a strong bond. Otto becomes The Boy’s trusted companion, navigating him through an intricate web of river passages, each twist and turn aimed at recovering Sam’s pilfered possessions.

And The Boy keeps clicking.

*clicking through youth

*clicking through youth

That’s “Pajama Sam: No Need to Hide When It’s Dark Outside.” A series of clicks in the Land of Darkness. A series of roadblocks with solutions already presented to the player five minutes ago, although intended for the player to miss on the first pass – future sight being 20/400.

Pajama Sam is an advanced game of concentration, of picking the matching cards and having to flip them both over if picked incorrectly. In its purest form, Pajama Sam is an hour-long puzzle with the pieces randomized each playthrough; items and socks placed randomly for Sam to find within The Darkness.

But this is no computer game to Sam, so mentally enslaved by the terror of The Darkness that he is determined to physically enslave The Darkness in a lunchbox that he calls his Portable Darkness Containment Unit. However, Sam can’t do it himself; he must adopt a false persona, that of Pajama Man. This facade gives Sam the courage to face his fears instead of being overcome by them, paralyzed in his bed.

Sam conjures up a world so rich and textured within his six-year-old mind that one has to wonder which movies his faceless mother let him watch before bedtime. This “Land of Darkness” is simply his closet, which is full of mundane items draped in pure Darkness; however, with the flash of the flashlight, the world becomes colorful, exciting, and palatable to the frightened six-year-old. A necessary illusion to complete his task, which – realistically – is collecting socks, but – figuratively – capturing The Darkness.

Once Pajama Sam has puzzled his way through the quizzical Land of Darkness, found his mask, flashlight, and lunchbox, he’s finally ready to face The Darkness.

Confidently marching through the home, up the winding stairs to The Darkness’ bedroom, Sam comes face to face with the bedroom door of The Darkness.

The Darkness’ bedroom door is a common wooden door. Ordinary. Non-specific. Yet, Sam can’t help but feel a pit in his stomach; however, instead of cowering, he tightens his Pajama Man mask, flicks on his flashlight, and grabs the doorknob; twisting it open to reveal The Darkness’ bedroom.

The Darkness’ bedroom is identical to Sam’s. Same furniture. Same sheets. Same mess. Same closet. Same everything – just darker.

Sam, gripped with fear and confusion, slowly steps through this dark copy of his own bedroom, shining his flashlight all around; but, The Darkness is nowhere to be found.

Just then, Sam hears a noise from the closet. A bumping.

The Darkness must be in the closet, just like in his own bedroom, so he tip-toes over to the closet – it’s locked – but after a short puzzle, he finds the key and unlocks the dismal double doors of The Darkness.

*Sam confronts his fears

*Sam confronts his fears

Sam waves his pillar of light around wildly, hoping to catch whatever it is inside the closet within the beam.

Then, Sam’s flashlight catches The Darkness, a black blob amidst the stream of yellow light; Sam, so afraid, nearly drops his flashlight and runs out of the room.

The Darkness, lurking in his very own closet, grins widely for a brief moment before realizing that Sam is trembling in fear. The Darkness’ grin turns into a melancholic frown: “You’re scared of me too?”

“I have no one to play with,” The Darkness proclaims.

Sam, shocked, questions The Darkness, only to find out that The Darkness just wants a friend – everyone is afraid of him, and Sam is just another of the countless beings in The Land of Darkness frightened to death of The Darkness.

Sam, realizing the error of his ways, swallows his six-year-old pride, puts away his enslavement-lunchbox, smiles, and proclaims, “I’ll play with you.”

And just like that, The Darkness and Sam sit down – together – in the black of the closet, to play a game of tic-tac-toe.

That is, until Sam’s mom calls him back to bed.

Sam hops up, waves goodbye to The Darkness, and says, “I’ll come by tomorrow night, and we can play another round!”

Unsurprisingly, upon leaving The Darkness’ closet, Sam ends up where he started: his own bedroom.

*Sam embracing The Darkness

*Sam embracing The Darkness

Sam and The Darkness are one and the same. An irrational fear manifesting itself into a vivid childhood hallucination, guiding Sam to the answer: Embrace the Darkness.

Both Sam and The Boy pretend to be heroes; both invent imaginary worlds in their heads, but for different reasons.

The Boy, afraid of The Dad and stripped of his obsessions every other month, invented a world inside his head to retreat, one where his imagination flourished with the things he enjoyed from The Mom’s house. The Boy languished in pure escapism, both physically and mentally.

Sam invented a magical world with a singular goal: overcoming his fears. At first, Sam believed he needed to defeat his fear, capture and hide his fear away in a lunchbox, but when faced with the truth, he overcame the fear and embraced The Darkness. All in a span of less than two hours.

It would take The Boy years – well into adulthood – to reconcile with the revolving door of his early childhood and the fear and animosity held toward his father, who – much like The Darkness – was a kind-hearted, albeit slightly misunderstood individual yearning for a connection with The Boy.

The Boy’s alright – but Pajama Sam is better.

(Originally published 8/11/2023)

#ComputerGames #PajamaSam #Autobiographical

*Iori rushes Ken in the digital equivalent of a samurai honor duel

*Iori rushes Ken in the digital equivalent of a samurai honor duel

*Lockout on the cathode-ray tube.

*Lockout on the cathode-ray tube. *Arcadian fishing pond.

*Arcadian fishing pond. *Pongo, Perdita, and pups transfixed by dancing light.

*Pongo, Perdita, and pups transfixed by dancing light. *Jackals and grunts huddle around bonfire of questionable origin.

*Jackals and grunts huddle around bonfire of questionable origin. *Night; Arbiter searches the Arcadian fishing pond; clubhouse and pool seen in the distance.

*Night; Arbiter searches the Arcadian fishing pond; clubhouse and pool seen in the distance. *Jake’s home in Arcadia.

*Jake’s home in Arcadia. *Master Chief overlooks fading Arcadia.

*Master Chief overlooks fading Arcadia.

*Hobby Lobby, model kit aisle, circa 2023.

*Hobby Lobby, model kit aisle, circa 2023. *Zaku II, Gouf Custom, and RX-78-2 gunpla

*Zaku II, Gouf Custom, and RX-78-2 gunpla

*the room in Rubicon

*the room in Rubicon

*for a fleeting moment, I am the captain

*for a fleeting moment, I am the captain *the bridge of the Avalon-1

*the bridge of the Avalon-1 *Imagination interrupt: illusion has stopped responding.

*Imagination interrupt: illusion has stopped responding. *space sims: the origin; one of these things is not like the other

*space sims: the origin; one of these things is not like the other *a boy and his blog

*a boy and his blog *bottom screen on the left, top screen on the right; also claw.

*bottom screen on the left, top screen on the right; also claw. *keeps going and going and going and going and going and going

*keeps going and going and going and going and going and going *tetrominos falling into place; not at all a Radiohead experience

*tetrominos falling into place; not at all a Radiohead experience *the boy and the man

*the boy and the man

*digital landscape of The Boy circa 2001, authors: unknown

*digital landscape of The Boy circa 2001, authors: unknown *The Darkness we know so well; stepping through the fog of youth

*The Darkness we know so well; stepping through the fog of youth *ghosts of the past haunt The Boy overlooking suburban splendor

*ghosts of the past haunt The Boy overlooking suburban splendor *we can be heroes, just for one day.

*we can be heroes, just for one day. *Et in Arcadia, Pajama Sam

*Et in Arcadia, Pajama Sam *Pajama Sam captured by the trees in The Darkness

*Pajama Sam captured by the trees in The Darkness *clicking through youth

*clicking through youth *Sam confronts his fears

*Sam confronts his fears *Sam embracing The Darkness

*Sam embracing The Darkness

*view from the afternoon; April 28th, 2023.

*view from the afternoon; April 28th, 2023.