I, INTRODUCTION or: Where Were You in 1993?

Monday through Friday, you sit in the back of the school bus near the weird kid whom no one talks to – his glasses taped up or some such trope – reading the same copy of Electronic Gaming Monthly until a new copy arrives, like clockwork, in your mailbox a few days after the first of every month.

The bus driver, a wrinkly old woman named Wanda or Bertha or something, keeps the kids quiet through the classic draconian tactic of screaming real loud, utilized whenever someone talks over her sacred Rush Limbaugh broadcast eerily timed with your bus ride home, blaring from a purple handheld radio dangling from a thick string on the rearview.

Wanda or Bertha or something has never yelled at you, your attention too focused on the cool gaming illustrations in Electronic Gaming Monthly and the new Smashing Pumpkins’ album – Siamese Dream – playing through your – even for this decade – vintage Sony Walkman Cassette Player, the left headphone speaker broken from repeated accidents, or at least that’s what you told the school counselor.

The bus stop is three blocks away from your home. You step off the bus into your neighborhood, walk up and down a few hills, climb the steps of your porch, and enter your home through the side door near the kitchen. You hear the sounds of Mom boiling water for your after-school Kraft Mac and Cheese, Sting’s “Fields of Gold” plays from a small black radio sitting on the windowsill near the stove, likely tuned to Star94, the only station that plays boring soft-rock ballads you won’t appreciate until you’re twenty-five years old.

*can you spot all the references?

*can you spot all the references?

Knowing you only have forty-five minutes to watch cartoons before Mom takes over the family television for her five o’clock episode of Days of Our Lives, you scarf down your Mac and Cheese while flipping through channels, quickly cycling through the lame shows your dumb sister watches – primarily Saved by the Bell and Clarissa Explains It All – and settling, finally, on Fox Kids.

X-Men is on; it’s the episode where Professor X tries to heal Sabretooth’s inner rage, only to find that, much like your own, it’s incurable – the rage is terminal.

You catch the tail end of the episode, quickly overwhelmed by commercials maliciously placed right before the end credits, likely to trick kids into sticking around in hopes of more content, and you fall for it: hook, line, and sinker. Sitting through a Crystal Pepsi commercial and Ronald McDonald enthusiastically telling you about the limited-time-promotional-six-inch-1957-McDonald’s-glass with every order of ten dollars or more.

And suddenly, the final commercial comes on: The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past for Super Nintendo, the game you’ve always wanted. “Now you’re playing with power – super power,” the ad seems intentionally designed to taunt you; and, much to your envy, your neighborhood rival has a copy and talks about it all the time – “It’s the best game ever made,” he says, knowing you don’t own a Super Nintendo and, also, knowing he will never let you come over to play it – because he hates you, or is secretly in love with you, or something.

Dad, opting for the cheapest route possible, bought a used Sega Genesis from the local Video Game Exchange instead of the Super Nintendo so meticulously outlined in your Christmas list, circled several times in frantic red ink. “It’s just as good, according to the guy at the store,” he told you as you opened the box that fateful Christmas morning. Unbeknownst to your father, this single act likely shaped all your gaming preferences, probably for the worse.

Along with the Sega Genesis, there was a copy of the game “Landstalker,” featuring an elfish blonde man wielding a glowing sword on the box art, reminiscent of a discount K-Mart-Link slicing at a skeleton, like Doom’s promotional art but for Dungeons & Dragons nerds and five-year-olds. Dad knew you wanted Zelda, but he picked up Landstalker instead. “The man at the store told me this is just like Zelda,” he said proudly.

You gave Dad a big hug that Christmas. None of this was what you wanted, but you loved it regardless.

*Shakedown, 1993

*Shakedown, 1993

If you haven’t figured it out yet, the year is 1993. The year of the first World Trade Center bombing and the infamous Waco siege. The year of Black Hawk Down and the signing of the Maastricht Treaty, ushering in the European Union and the insufferable conspiracy theories of reactionaries for years to come. The year in which space probe Galileo reached Jupiter, the closest a hunk of Earth-metal has ever come to a Roman god; and, of course, most importantly: the year Landstalker for the Sega Genesis was released in North America.

Grandma Susu on my mother’s side would call Landstalker a computer game, making no distinction between the hardware the game is actually played on because it’s all goofy kids’ stuff anyway – a small hint as to the meaning behind this site’s name; and, keeping with the site’s theme of writing about computer games that are not computer games but actually console games, this article will cover Landstalker for the Sega Genesis in much greater personal detail than you asked for – and having not asked to begin with, this seems like a fairly good deal.

Landstalker, or Landstalker: The Treasures of King Nole, is a Japanese adventure game not at all inspired by Nintendo’s Zelda series. It was developed by Climax Entertainment and released on the Sega Genesis by the renowned publisher, you guessed it, Sega; originally released in 1992 for Japanese audiences and localized in English in 1993.

Landstalker was written and directed by Kenji Orimo, who immortalized himself within the game as the character Pockets, along with a team of developers who could best be characterized as misfit-sadists. This development team would eventually earn a cult-hero-like status among the most pedantic of niche computer gamers: Sega fans.

Individuals such as Yasuhiro Ohori, the map designer, and Masumi Takimoto, the key programmer, become particularly important in this development team’s mythos, something we will cover in the tentatively planned analysis of Alundra for PlayStation, which will most likely never happen.

*David Koresh, Kenji Orimo & Pockets, Alundra, and Jupiter

*David Koresh, Kenji Orimo & Pockets, Alundra, and Jupiter

The year 1993 was dominated by Nintendo supremacy, with Star Fox and Super Mario All-Stars reigning supreme in the mushroom-crowned world of gaming. The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past and Link’s Awakening captured the collective-computer-gamer-consciousness, and two out of the three Famitsu Hall-of-Famers were Nintendo titles, while eight out of the top ten highest-grossing games worldwide were on the Super Nintendo.

Sega already had Sonic, a rival to Mario, but something was needed to rival Zelda, which is where Landstalker comes in – Sega’s Zelda-Clone-That-Is-Not-A-Zelda-Clone. That being said, the arrival of Landstalker in North America did very little to change Nintendo’s stranglehold on the North American gaming hivemind. Although well-received at the time for its unique take on the action-adventure genre, Landstalker flew under the radar for most American gaming outlets, achieving true success only in Japan – a country where respecting your time is not a prerequisite for popularity.

And while I characterize Landstalker as a computer game that does not respect your time, experiences will differ for everyone. It’s all a matter of perspective, literally.

The color I perceive as blue could be perceived as red by another, or vice versa, with the common link being the words used to describe the thing. After all, how would you describe blue other than “blue” or “cool,” both words of nonsensical value when used by themselves. Much like describing a game as “fun” or “good,” meaningless terms that mean different things to different people.

One individual may have reveled in Landstalker’s charms upon its 1993 North American release on the Sega Genesis, while another might have embarked on its pixelated quest via the PC version on Steam; god forbid, there could even be a lost soul entranced in the forever cursed and truly evanescent Nintendo Switch Online version of the game.

The point being: subjective computer game ephemeral.

As for myself? I just downloaded the ROM and played it on an emulator.

II, EMULATION REVISITED or: Trip the Light Nostalgic

What drives someone to purchase a CRT television set from the ’90s, prop it up on a folding table in the corner of their office, and play old television programs, anime, and video games on it – in 2023? Is it a longing for the past? The lugubriousness of growing old – or simply a pretentious display of esoteric exoticism? An attempt at retro-coolness only a select few are unfortunate enough to be privy to. A peek into the antique mind, trendy retrograde highly resistant to the new-age; the adult version of wearing tripp pants and a Misfits shirt to your religious grandma’s 95th birthday party.

In this chapter, we will attempt to answer these questions, but first, let’s explore ancient plastic and trip the light nostalgic.

Some believe that old plastic must be respected, collected, and worshiped on the sacred altar of computer game ephemera. Others argue that by collecting old plastic, we are, in a way, preserving the intended state of the video game, as if we are doing some esoteric concept a solid by hoarding products that will one day release enough deadly chemicals to kill a small child – a sacrifice to the gamer gods so that we may be blessed with many future computer games.

Some may delude themselves into believing that buying an original boxed copy of EarthBound for $2,800 from some sweaty loser off eBay actually supports its niche director, Shigesato Itoi, and somehow increases the likelihood of a North American Mother 3 localization.

These hypothetical-strawman-people are insane; and, well, whatever they believe – I believe the opposite; and whatever they say I am, that’s what I’m not. I believe ancient plastic belongs in the garbage. Or, if you’re eco-friendly, recycled at your local electronics recycling plant. I believe any game older than 10 years might as well be laundered, and that stacking aged plastic on a shelf is peak human hubris, akin to Donald Trump filling his hotels with gold.

Developers are not harmed by downloading a 10-year-old game without paying for it. Ignoring the fact that within the retro gaming community, the majority of collected and played games are far out of fashion, to the extent that the original publishers no longer care about them or the game in question has been re-released by an entirely different company with none of the original development team’s involvement; the vast majority of developers are paid by the hour or receive a salary – they do not earn commission from computer game sales and are typically assigned to different projects immediately after the divine birth of a computer game.

Of course, the counter argument would be that by not supporting – buying – a computer game, you are potentially harming the studio as a whole, which could have a downstream impact on the job security of salaried developers in the long run. And yes, there is some truth to this argument; however, when it comes to 10-year-old computer games, this argument loses its validity. The development team has moved on – it’s time to let go.

Do you want to backup your old collection of Sega Genesis games? You are just a few clicks of a mouse away from doing so.

The only person upset about downloading ROMs is the cheap-suit Nintendo executive who devised the eligosian scheme of listing the Sega Genesis Collection as a free download on the Nintendo Switch online store, only to surprise you – with no warning in the listing – that you need an Expansion Pass after downloading and booting it up.

*Nintendo turns the Sega Genesis into a theme park with a $42.19 cost of admission

*Nintendo turns the Sega Genesis into a theme park with a $42.19 cost of admission

Do yourself a favor; if you want to support Sega, buy the SEGA Mega Drive & Genesis Collection on Steam – which includes uncompressed ROMS of every title in the collection. Yes – Sega is just giving you the ROMs to use as you see fit; a rare corporate attempt at true game preservation.

Buying cartridges is not game preservation, playing games on Nintendo’s demonic online service is not game preservation, and purchasing digital only releases is not game preservation. Modern developers, even those we revered as children, such as Square(Enix) and Nintendo, are now more interested in endlessly selling you the same classic games at full price on new consoles in perpetuity, selling an experience instead of a computer game; a theme park of fugacious feelings – emotional manipulation.

Install SoulSeek or go to your preferred ROM site and download all the games for free.

This is the obligatory point in the article where I state that the “on computer games” staff does not support piracy, and will be citing this paragraph when lawyers contact us; this whole chapter is satire, or something.

Anyways, I once engaged in an online argument about the viability of classic computer game remasters – a big mistake, I know. Of course, I took the position that these remasters don’t need to exist and that the original games are fine, offering the optimal way to play in the original developers’ intended vision.

The counter argument was that a new generation of fans would have the opportunity to experience the game. To this, I posed the question: why? Why can’t they simply play the original? The response I received was that it’s too expensive. Buying a physical copy of the game, the console, the controllers, and the optimal television – it all adds up and becomes too costly. After all, a Sega Genesis, two controllers, and a copy of Landstalker would cost about $300; and we’ve already covered how expensive an original copy of EarthBound is.

The barrier of entry is simply too high!

Well, while you’re debating which car title to leverage a loan to purchase that original copy of EarthBound from EpicLoliFan69 on eBay, I am just downloading the game – for free.

The purchase and collection of little cartridges and discs with data on them isn’t noble or necessary. The games don’t “last longer” for preservation’s sake and this act does not support the original developers; ripping the ROM image and keeping it on a drive is true preservation, or just downloading it online – it’s the same thing the cartridge is doing, only not proprietary, locked, or restricted in any way, and much easier to transfer to another medium if necessary. A ROM of Landstalker for the Sega Genesis on three million hard-drives has a much longer half-life than the coveted, but inferior, ancient plastic models that are no longer in active production.

If this offends your computer-gamer sensibilities, sit down, breathe, and think for a moment. Ask yourself: why? Why collect the games? Why give in to the consumerist drive to collect eco-waste?

You want to support the developers. You want more games from your favorite studios. I get it.

If you want to support a new game, that’s great; buy the new Grand Theft Auto game because you like Rockstar Studios and want more Grand Theft Auto games – that is completely valid and should be encouraged; just don’t pretend that buying the original Grand Theft Auto for PlayStation is helping anyone other than yourself and your own egotistical drive to tell people you own a copy of the original Grand Theft Auto for PlayStation.

So, in protest – and, importantly: not to be cool (I swear) – I purchased a translucent 13″ color SecureView CRT television set, model number S13801CL, from eBay, the type of television set used in prisons in the 90s and early 2000s; clearly-clear in make and model, so inmates couldn’t hide their drugs inside; and, “only slightly used.”

The SecureView CRT television set was delivered in a huge box filled with protective foam and peanuts on June 16th, 2023.

Each SecureView, typically, has a prison cell number carved into the casing, and mine is no different: R06190 – that’s the television’s name now.

*R06190; displaying Ranma ½ & Landstalker, prison cell number included

*R06190; displaying Ranma ½ & Landstalker, prison cell number included

I often wonder who was watching this television set while it sat in a dank prison cell – and what programs were they watching on it? What were they in prison for? Did they kill someone, or was it a petty crime like smoking weed? Maybe it was never used, simply languishing in an unused prison cell. And most importantly, how did it end up in the possession of some seller on eBay? Was the seller the inmate who used the television set, somehow keeping it as a memento of their time in prison – or was it something more boring, like a prison auction someone was lucky enough to attend?

Naturally, I searched the cell number online alongside a variety of keywords; but, no luck – it’s a mystery, forever part of R06190’s charm.

Having done no research and making this purchase for aesthetic value alone, I quickly discovered that R06190 only connects to external sources through an RF coaxial port. So, I bought a cheap HDMI to RF adapter. I plugged my laptop via an HDMI cable into this adapter and then connected the coaxial cable from the adapter into the television set. As a final – and most crucial – step, I downloaded RetroArch, several console cores, and a vast 60gb ROM – ISO image pack.

And suddenly, just like that – I’m playing with power, super power; just like the Zelda commercial continuously taunted in 1993. I was playing with the power of every pre-2005 console at my fingertips, all on a cool see-through CRT television set that my 11-year-old self would have killed other kids to get his hands on.

Pressing the power button for the first time, R06190 hummed electric, and a surge of static jumped onto my fingertip as the magic happened. Within the ethereal realm of the clear-body-cube, a filament of tungsten became aglow with celestial energy, bestowing a fairy-fire upon the cathode nestled deep within the belly of the beast. Electrons, like little woodland sprites, woke from their slumber, harmoniously buzzing and guided by the electrode wizard to a phosphor-laden tapestry; all happening in one mesmerizing instant: an image born – the image of the divine, the eternal babysitter of children throughout the first-world: moving pictures composed of rainbow electrolight.

Or something like that.

Contrary to immediately playing computer games, I used this magical power to watch Toonami Aftermath and old anime. After bouncing around from the original Dragon Ball, Cowboy Bebop, and Yu Yu Hakusho, I eventually settled on Ranma ½; and the results were glorious – if I was chasing that early 2000s Toonami feeling, I had nearly caught up with it.

Sixty episodes of Ranma ½ later and I started to notice something: a staticky sparkle scaling upward on the screen. Like 90s cable television, but with a really bad connection. Hard to notice, but once noticed: impossible to ignore – how would I ever play computer games on R06190 with such an imperfection?

After much fooling around with settings and switching coaxial and HDMI cords to no avail, I made the decision to purchase a new HDMI to RF adapter; finally deciding on the elegantly named “HDMI Modulator RF Converter RCA Coaxial Composite VHF UHF SDR Demodulator Adapter w/Antenna in/Out & Channel Switch for Roku Fire Stick Cable Box HD Digital AV Component Video to Analog NTSC Coax TV” model.

This model was much bigger, bluer, and more expensive than my first adapter, and the “modulator” title made it seem far more serious – like giving a tier-1 technical support representative the title of “engineer.”

After purchasing the big blue box, I had to wait another week for its arrival. Fortunately, my short attention span was occupied during this time as I was in the midst of writing an analysis on the game Popful Mail for Sega CD. Being one-track-minded and having been diagnosed with ADHD when I was nine, I can only focus on one thing at a time. Hence, the few staticky sparkles that accompanied my television programs, used mainly for background noise while writing, didn’t bother me much at the time.

The modulator arrived the day after I finished my analysis, serendipitous timing since I was eager to play my next seemingly randomly generated interest – Landstalker for the Sega Genesis.

After some preliminary testing, the new modulator worked perfectly, the sparklies were gone; the image was crystal clear, well, as clear as an RF coaxial would output, and everything was good at that moment. My wild bet on “it’s more expensive so it must be better” actually paid off, for once.

Having prepared for this moment, I had multiple classic-console-controller-to-USB-adapters at the ready, including one for Sega Saturn and PlayStation. So, I hooked the Saturn pad up to my laptop, ran RetroArch, navigated the menus and booted up Landstalker.

*the three elements that make this setup work: laptop, hdmi to rf modulator, R06190, and a Sega Saturn pad

*the three elements that make this setup work: laptop, hdmi to rf modulator, R06190, and a Sega Saturn pad

Sixteen paragraphs later and I have justified this ridiculous excess for long enough. What is the true reason for all this stuff? I could easily play any of these games on my PC setup with one of many 1080p flatscreen monitors – why purchase an old CRT television to do it?

I could make the excuse that a modern flatscreen doesn’t capture the intended essence of the classic games I wish to play; or that the large resolution stretches out the pixels, making the games look nasty; but I don’t really care about any of that.

What I care about is esoteric; capturing the nostalgic quintessence – that feeling of staying up late on those summer nights in Charleston at my grandma’s house; a time when I would call my highschool-girlfriend on a Nokia phone and fall asleep on the line while watching late-night Roseanne together, or just ignoring her calls altogether to play computer games instead, only to tell her, “Sorry, I missed your calls. I fell asleep” the next day.

It’s about chasing the dragon, knowing that dragons don’t actually exist.

It’s about being a kid again.

And, contrary to what I previously typed, I think it’s pretty cool to play old computer games on a translucent ’90s prison cell CRT television.

In conclusion, never trust someone who justifies their excess with over one thousand words.

III, FUTURE FOE SCENARIO or: Characters, Concepts, and Context

The ’90s were a time when every Japanese computer game’s artwork was run through the homogenization factory, the gentrification presser, and then systematically entered into the American hivemind – if the hero was lithe and pretty, they’re now buff and manly; if they were short and goofy, they’re now tall and handsome.

Nigel, the hero of Landstalker, is no different. Originally depicted in 1992 on the Japanese box art as a tall elf boy, thin and quick, executing a solitary slice of his saber with a dark specter looming behind him; the North American box art depicts him as a fairly-built man with chiseled jaw and mullet, standing upon a stone slab towering above a skeleton in a battle-ready stance. His sword held high and glowing with magical power, akin to Doom’s original box art but without all the nightmare-inducing demonic forces eager to rip your legs off – not surprising considering every computer game is now a Doom clone in some form or fashion.

*NA Landstalker, Doom, and JP Landstalker boxart compared

*NA Landstalker, Doom, and JP Landstalker boxart compared

Our hero’s name, Nigel, isn’t even his true name. His original Japanese name is Ryle, a far more exotically fitting name for a 90-year-old elf who has maintained his youth through elven lineage; and, combining all these changes, we get a hero who, although possessing the same sprite throughout each regional release, somehow feels far more like an action hero — a mix of Walker Texas Ranger and MacGyver — than Lord of the Rings’ Legolas or Link of Zelda fame, of which – for the third time – Landstalker is not at all like.

Although much better suited for silent-protagony, Nigel has a personality and talks frequently, coming off as a one-track-minded individual who only cares about stuff as opposed to people. He is, after all, a treasure hunter by profession, and he is very arrogant in his abilities, which is personified in his perfectly animated walking animation, an overly confident strut to end all struts.

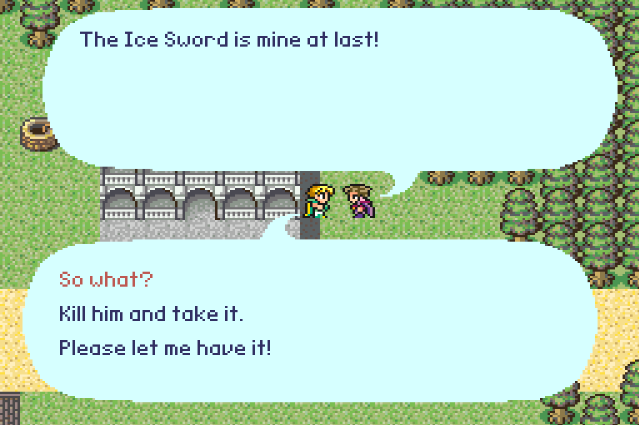

Hailing from the town of Maple, Nigel has ventured to the island of Mercator on a mission to find King Nole’s lost treasure, guided in this direction by a wood nymph encountered during the game’s prologue, the oddly named Friday.

The name “Friday” derived from Old English, meaning “day of Frig,” which itself is based on the Norse goddess Frigg. This either implies that Frigg exists in Landstalker’s mythology or that the writers simply didn’t care — an irrelevant tangent, but interesting nonetheless. Running this line of thinking to its conclusion, every game not set on Earth should have its own incomprehensible language, flora and fauna, and architecture; as it’s extremely unlikely for physio-and-socio-evolutionary-progress to be so similar from world to world.

Tangents aside, Nigel is accompanied by Friday throughout his entire adventure on the island of Mercator, serving as Nigel’s guide and, at times, his moral compass; notably reprimanding Nigel when he agrees to be a little girl’s boyfriend in one of the game’s early towns.

Friday resides in Nigel’s backpack when not popping out to save, lecture or provide guidance to Nigel – doing who-knows-what in there. It is heavily implied that Friday is in love with Nigel, as she is quick to verbally attack any female character he interacts with and often expresses her joy in adventuring with Nigel; a subtle touch not explicitly stated but left for the player to infer.

*Nigel and Friday, honeymooning on a raft

*Nigel and Friday, honeymooning on a raft

Friday is Nigel’s companion, through and through, much like Navi or Tatl from the Nintendo 64 Zelda titles. Surprisingly, these Zelda companions came after Landstalker, and the similarities to Friday are too obvious – all being small fairy beings that talk way too much. Clearly, the Nintendo team was inspired by Nigel’s relationship with Friday, prompting them to add a fairy companion of their own in future Zelda games; a rare case of the inspired inspiring the inspirer.

Nigel’s time on the Island of Mercator is fraught with a number of challenges. Just starting out, he ends up knocked out and awakens in the tribe of Massan, occupied by bear-like beastmen at war with the neighboring tribe of Gumi, also occupied by bear-like beastmen – just of a different fur-color.

Both tribes harbor hatred towards each other due to this minor difference in coloration, an obvious social commentary quickly undermined by the fact that Gumi tribesmen end up kidnapping a girl from Massan and attempting to sacrifice her to Orc Gods, validating Massan’s initially-irrational hatred. Nigel – of course – intervenes, saving the girl and slaying the Orcs; and, it turns out that the Orcs were mind-controlling the Gumi tribe, or something, so no harm no foul and they’re all friends now.

Afterwards, Nigel and Friday venture to the capital city of the Island of Mercator, which is fittingly named Mercator and is governed by Duke Mercator, a naming convention mirroring the song Black Sabbath by the band Black Sabbath on the album titled Black Sabbath.

In terms of town design, Landstalker is the type of game where the inn only has one room, consisting of the reception desk and six beds for everyone to sleep in. What the receptionist does when you’re sleeping, while a good question, is not something we will be exploring in this article.

Mercator is easily comparable to the various incarnations of Hyrule Castle Town, from Zelda – a series that Landstalker is nothing like – and the city itself is huge for Sega Genesis standards, encompassing multiple zones with five or six homes in each, and a huge manor with all manner of hidden passages, pun intended.

Each home in the city has a family of NPCs inside, all with their own weird stuff going on; the attention to detail and nuance of the world is impressive and, as a result, feels fleshed out and thoroughly lived in.

*Island of Mercator, as pictured within the in-game map

*Island of Mercator, as pictured within the in-game map

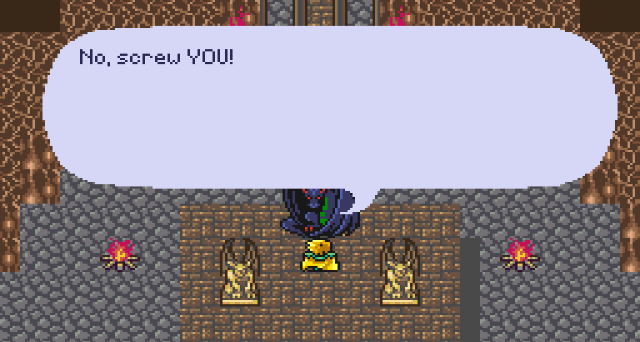

Duke Mercator, after a series of dubious quests, summons Nigel and two other heroes to his manor to partake in a “little game,” aimed at defeating the local wizard – Mir – who resides in a nearby tower. Duke Mercator claims that Mir is forcing him to fork-over exorbitant sums of gold, thus justifying his over-taxation of the locals; and, of course, the locals buy this story, all too eager to encourage Nigel to slay the wizard – gold being the ultimate motivator of human slaughter.

Like all political excuses, Duke Mercator’s story turns out to be a lie. As Nigel conquers the wizard’s tower and confronts the wizard at its pinnacle, it is revealed that the wizard is, in fact, Duke Mercator’s brother. Mir, being aware of Duke Mercator’s true nature as an evil man attempting to locate King Nole’s treasure for himself by using the locals’ tax money to fund his treasure-hunting escapades, is imprisoned by his brother in the tower to prevent the truth from being revealed to the local people of Mercator.

From this moment onward, Mir assists Nigel in his quest for King Nole’s treasure, and Duke Mercator becomes the main villain. Nigel often ends up chasing the Duke’s coattails, always one step behind the Duke until the inevitable final confrontation.

*Duke Mercator challenges Nigel

*Duke Mercator challenges Nigel

The Island of Mercator, both conceptually and thematically, is a lush landmass teeming with beaches, swaying palm trees, dense forests, and treacherous mountain ranges. Secrets and hidden passages await around every corner, with dungeons bursting with treasure scattered throughout the map – the perfect enclosed system for Nigel’s 16-bit adventure.

The dungeons, caverns, numerous pits, and wells that must be traversed for treasure all boast a level of graphical fidelity that is impressive for a 1993 computer game, especially when paired with the unique isometric perspective, something not found in many – if any – action-adventure games up to that point. The splotchy watercolor quality of the textures and the carefully selected color palette enhance the game’s overall aesthetic theme – one of cheeriness or gloominess, with no in-between; you’ll be in a town full of shiny happy people holding hands, then go into a cellar in one of the home’s only to find a sickly green colored dungeon littered with bones.

Whether in a moody dungeon or a cheery town, the art direction is impeccable, truly capturing the intended mood envisioned by the directors. Unfortunately, due to a very dumb choice on behalf of the development team, a huge black bar encompasses the full length of the bottom-fourth of the screen, literally cutting the visual space by 25%; a truly baffling decision, likely made to save space for dialogue boxes, which fill that space when there is dialogue, but the empty void remains even when the dialogue ends.

This big black bar makes Landstalker feel cinematic, in a way, like a letterboxed movie on a widescreen television, which – supposedly – some people actually like; however, I don’t believe it – these hypothetical people are fooling themselves.

Give me full screen or give me death.

*the bar, ever-present and never-ending – but why?

*the bar, ever-present and never-ending – but why?

The music, while suitable for each environment, is mediocre at best. I typically consider a game’s soundtrack “good” if it has two or three tracks that I save to my “computer game music” playlist on YouTube. However, no such standout tracks are found here. The music is competent, but it lacks catchiness or memorability in any way.

The music does succeed in capturing the mood of each environment. Towns typically feature the same cheery, upbeat, and bouncy theme, while dungeons consistently have a dreary and despondent melancholic track that lacks much deviation. As you can imagine, this repetitive soundscape becomes tiresome after an hour or so of dungeon-crawling.

Similarly, Nigel’s overworld wandering is accompanied by the same musical score throughout the entire journey. The number itself is epic in scale but too upbeat for simply walking through the forest; however, it works well when a monster attacks you – and to the game’s credit, such encounters happen frequently.

If the music accomplishes one thing successfully with its ongoing epic pulsations, it’s instilling a sense of continuously moving forward, propelling the player to jump and slash their way into new adventures.

And you’ll be jumping and slashing a lot.

IV, GAMEPLAY or: Not a Zelda Game, Seriously

Landstalker is an action-adventure game with light role-playing elements. Some would say it’s a lot like Zelda – A Link to the Past, only coming out a year before the Japanese release of Landstalker in 1992. However, I wouldn’t make the Zelda comparison because it’s cheap, easy, and meaningless. One should not need knowledge of another thing to understand a different thing. It’s laziness, and while I am lazy to an extent, I am not lazy about computer games – computer games are very serious.

From the moment you boot up Landsalker, you’re presented with an in-engine cutscene of Nigel platforming through a dungeon called the Jypta Ruins in the year 312 of Gamul. This scene is a vertical slice of everything you need to know about Landstalker. Nigel is shown running from a boulder trap, jumping from platform to platform, in an odd isometric perspective. Nigel is then shown working through a jumping puzzle where platforms float and move around in the sky, and he must time his jumps carefully to land on each one, finally climbing up a vine rope into a room where he cuts down some obstacles blocking the path to a large treasure chest full of treasure.

If the prologue does not look appealing to you, turn the game off and move on to something else because Landstalker’s prologue represents the past, present, and future of your experience.

*part of the prologue, heavily compressed with every other frame removed

*part of the prologue, heavily compressed with every other frame removed

Landstalker is the type of game where you find a large treasure chest in the bowels of a dungeon, only for a lone solitary key to be inside. Who is putting these keys inside chests, and why have they never been used before?

Landstalker is also the type of game where a switch in the basement of a manor opens a door two floors above you for approximately thirteen seconds. The architect of the manor either lost his mind or was extremely concerned about security.

At its core Landstalker is a game about jumping and slashing through puzzles and platforms. The sound designers knew this very well when they made the jump sound-effect identical to Sonic the Hedgehog’s, a euphonious “whrr-oup!” noise that fits Sonic’s vibrant happy worlds and, at least early on, fits Landstalker’s as well.

Landstalker is, first and foremost, a platformer with a fully traversable overworld filled with monsters that must be slain before each platforming section. Sometimes, the overworld zones themselves are platformers. In between this platforming, there is travel, towns, and puzzles, all in an effort to do more platforming.

Controls make or break a platformer, so let’s discuss the controls. But first, we have to address the elephant in the room: the game’s perspective. Landstalker is presented in an isometric perspective, setting it apart from adventure games like Zelda or Crystalis which operate from a top-down or side-view perspective, where left, right, up, and down are clearly defined.

Directionals aren’t so well defined in Landstalker. Being a computer game that employs an isometric perspective, the playfield is viewed at an angle instead of a flat view, which gives Landstalker a faux-three-dimensional feeling, sometimes referred to as a three-fourth perspective or two-point-five-dee perspective.

The isometric perspective makes Landstalker visually striking and immediately intriguing to the uninitiated, pretending – successfully – to be more graphically advanced than it actually is, which is a feat all its own. However, this perspective presents an array of problems, such as challenges with depth perception and the controls themselves.

Landstalker has either the worst controls ever or the best controls ever, depending on your perspective of the perspective. Since directions are ambiguous based on how Nigel is standing and where he’s facing, it’s not as simple as left, right, up, and down. Instead, each direction on the d-pad functions as forward or backward depending on which direction Nigel is facing; additionally, since it’s a pseudo-three-dimensional plane, you have to be able to traverse the pseudo-plane, which involves moving in-depth – closer or further from the screen. To achieve this, the game uses diagonal directions to shift Nigel’s position on the plane, with the required diagonal varying depending on Nigel’s position; basically, pressing a diagonal turns Nigel to face a different direction, you then use the left – right – up – down directionals to move him forward or backward in that new direction.

*Saturn pad with crude paint drawings and official illustrations explaining the importance of diagonals

*Saturn pad with crude paint drawings and official illustrations explaining the importance of diagonals

It’s all very hard to explain, and when you first boot up the game and are given control of Nigel, you won’t know how to move him around properly. Left, right, up, and down all move him forward or backward, creating an interesting “is my controller broken?” phase. Yet, somehow – and again it’s very hard to explain without experiencing it yourself – once you figure out that diagonals turn Nigel to face a different direction, it becomes very obvious how to move around properly; becoming accessible and natural after twenty minutes of play.

Landstalker, being an early Sega Genesis game, used the original Genesis pad, which consisted of three face buttons and a luscious d-pad that included all diagonals – a feature Sega kept on all their pads until the Dreamcast, where it was removed for an inferior four-directional pad.

The point being, Landstalker should be played with a pre-Dreamcast Sega pad, and that is exactly what I did. Using my Saturn pad, controlling Nigel – diagonals and all – felt natural and deliberate; playing with any other type of d-pad would have been a nightmare scenario.

Being designed around the Sega Genesis pad, Landstalker’s controls are very straightforward: press A to attack, press B to jump, and the third face button can also be used to attack. Oh, and press Start to access the item menu – that’s it; retro simplicity at its finest.

*Traveling the overworld; featuring phallic mushrooms and Nigel’s strut

*Traveling the overworld; featuring phallic mushrooms and Nigel’s strut

Landstalker’s gameplay loop starts off strong and never changes: go to a town, there’s a problem, the problem is solved by doing something in a nearby dungeon, travel outside of town to locate the dungeon, complete the dungeon, and finally return to the town for your rewards; typically, after solving the problem, some new path opens to a new town. This formula was incorporated in several adventure games of the era.

Every zone is connected by large environmental “overworld” zones, which are not much different from dungeons, as both are complete with puzzles, monsters, and platforming; but you can’t simply go everywhere at the start of the game, various obstacles block progression until certain events are completed. For example, saving the kidnapped Massan girl causes the Massan tribesmen to clear a landslide, allowing you to progress to the next area.

Notably absent is the acquisition of equipment that gives Nigel new abilities that would allow him to reach new areas. This inclusion would have helped to keep things interesting, although it would have made the game more like Zelda, a game that Landstalker is not at all like — I swear.

Most of your time in Landstalker will be spent crypt-walking and dungeon-crawling. The first three dungeons really shine in terms of actively keeping you engaged without being too frustrating; showcasing the early freshman versions of each isometric puzzle and platforming trick you’ll encounter later on.

These puzzles include – but are not limited to – box puzzles where you pick up the box and place it on a button, box puzzles where you stack boxes to get on a higher ledge, timed button puzzles where you jump on a button then race to the door it opened before the time runs out, and the classic “stand in room for two minutes doing nothing until the door opens,” which is actually not classic – just stupid.

The Wizard Tower dungeon, where Meractor sends you to defeat his brother, is a high point of the game and where the difficulty starts to ramp up. Featuring a blue-gray tile set with putrid green flooring, giving the tower a foul swamp aesthetic. The wizard at the pinnacle taunts you along the way; and like any good Wizard’s tower, it’s full of trick rooms, invisible walls, spike traps, and illusions that – admittedly – forced me to use an online guide at least once.

The Wizard Tower is the type of level in a computer game that a kid in the ’90s would get stuck on for weeks on end; occasionally booting up the game and messing around only to accidentally stumble upon the correct answer to a puzzle weeks later. Depending on your perspective, this can be either really cool or unnecessarily cryptic. This type of experience is hard to replicate in 2023, where the temptation to access detailed online guides is always looming in the computer-gamer-subconscious.

The puzzles throughout the Wizard Tower, as well as the entirety of the game, are constantly surprising, incorporating a level of ingenuity that often comes as a shock within the confines of the game’s seemingly basic structure. While many puzzles involve “picking up the box and placing it on the button,” others require you to “pick up six boxes and stack them on top of each other at an angle to use as a ladder to reach a button that opens the exit for two seconds,” often utilizing timed gates and ladders to get the player’s heart racing.

*Landstalker gets creative with puzzles; button that moves statues, but you need to use Nigel’s head to ensure they move along the right path.

*Landstalker gets creative with puzzles; button that moves statues, but you need to use Nigel’s head to ensure they move along the right path.

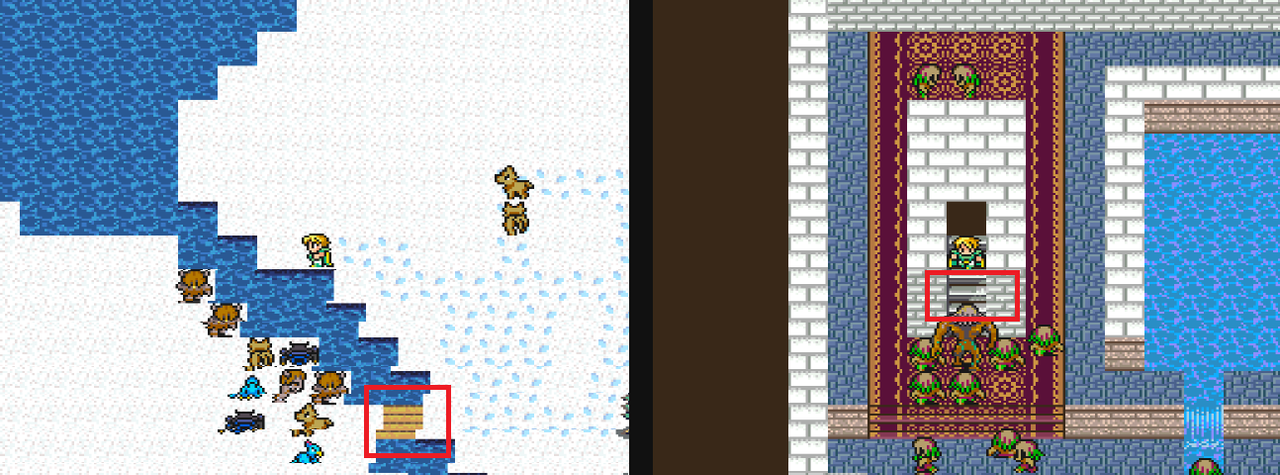

What happens after the completion of the Wizard Tower is the true highlight of the game. A scenario that illustrates the potential Landstalker possesses to create memorable moments that blend gameplay and storytelling into a perfectly woven tapestry.

Once you get back from the Wizard Tower and confront Duke Mercator, he steals all your MacGuffins and trapdoors you into the dungeon below his manor – a vast underworld with fiends in every room, quick but satisfying puzzles, and brisk platforming through the dungeon floors back up to the manor proper.

After fighting through filth to return to the main floor of the manor, you discover that Duke Mercator has kidnapped Maple’s princess and trained all the knights to attack you on sight, necessitating the slaying of knights who once spoke with you as a friend.

After considerable bloodshed, you ascend the top of the manor and enter the chamber where Maple’s princess is being held; but suddenly, the Duke’s winged dragon-knight swoops in through the window, snatches the princess, and swiftly departs. Hastily, you make your way to the window only to realize that the dragon-knight has absconded with the princess, taunting you as they fade into the distance. Turning back to the window to descend the manor, you find the knights have closed in on your position, compelling you to leap from the manor’s pinnacle and land in the courtyard below, directly in front of Duke Mercator’s grandiose statue of himself.

Duke Mercator has stolen all of your stuff, made off with the princess, and sailed off from his dock to the next town over. Moreover, he has destroyed the local lighthouse, preventing you from following him.

This set-piece utilizes every asset of the game to create an experience that feels exciting and worthwhile. Combat, puzzles, platforming, and cartoony storytelling blend together in a way that momentarily suspends your worldly awareness; the computer-gaming-end-goal of any worthwhile developer.

Sadly, such moments do not recur, and the game only worsens from this point onward.

*never trust a man with a large statue of himself in his front yard

*never trust a man with a large statue of himself in his front yard

In an effort to painstakingly detail every aspect of the game, monsters roam the Island of Mercator in abundance; Landstalker, after all, would be a fairly boring action-adventure game otherwise. There are only a few types of monsters, which can be summarized in one long comma-separated sentence: slimes, phallic mushrooms, orcs, giant cyclops, bipedal unicorns, some worms, armored knights, and mutant ninjas.

Each monster has multiple recolored variants, representing harder-hitting and bulkier versions of the originals. Slimes and mushrooms deviate from this pattern by becoming more aggressive and inflicting different status effects as their colors change; and, like all systems of this nature, there is a standard progression to these recolored variants, with green slimes being encountered early-on while stronger purple slimes lurk in the halls of the final zone.

Combating these enemies is not complicated. Pressing A makes Nigel slash with his sword, and jumping while attacking can reduce some of the frame data, enabling Nigel to attack slightly faster. Proper positioning within the isometric world is key to victory; however, if Nigel is too close to a tree or other obstacle — and sometimes it’s hard to tell — his attack will bounce off the environment with a small ding, leaving him vulnerable to attack, which happens all too often; additionally, the perspective can create an illusion that enemies are in front of Nigel when they’re actually slightly to the left or right in the foreground or background, causing Nigel to miss when attempting to attack them.

Bosses are a rarity, but when they do appear it’s typically at the end of dungeons; however, this is not always a guarantee, with some dungeons ending unceremoniously. When bosses do make an appearance, they often turn out to be altered versions of existing enemies. The first boss fight, for example, is two normal orc monsters recolored red, which you find as normal enemies later on.

As the game progresses, you will encounter enormous golem bosses brandishing hammers. To evade their attacks, you must time your jumps precisely when they bring their hammers crashing down to the ground. This adds an additional layer of complexity to the bosses, going beyond the usual button mashing that occurs far too often.

Though most bosses fail to make a lasting impact, Mir and the final boss defy this trend, outliers to the standard formula. Mir’s battle unfolds like a game of dodgeball, but instead of nerf balls, they’re fire balls. As for the final boss, well, find out for yourself – or don’t; whatever you want to do.

*golem boss approaches!

*golem boss approaches!

Landstalker’s combat can be likened to white bread, yet thanks to the impeccable sound design and elegantly simplistic animations, it takes on a lightly buttered, smooth, and satisfying quality. This remains true despite the tendency for combat to devolve into bunching enemies together and repeatedly pressing the attack button, exploiting monster recovery frames; a common characteristic found in 90s action-adventure games.

Combat doesn’t change much throughout your adventure; however, there are a few notable exceptions. From the very beginning, there’s a sword gauge on the UI. Initially, it serves no obvious purpose except to sit there, looking pretty, and to pique the players’ interest by teasing the idea that it’s – obviously – used for something, but what exactly?

Eventually, Nigel discovers the Magic Sword, which allows the sword gauge to charge up. When fully charged, Nigel unleashes a flame-slash that hits harder than the default attack. Ultimately this upgrade is nothing special; however, it marks the first of four attack upgrades that get progressively more exciting

In due course, Nigel acquires the Thunder Sword, which operates similarly but with electricity. This is followed by the Ice Sword, capable of shooting a small ice-tornado projectile. Lastly, Nigel obtains the Sword of Gaia, which triggers a full-screen earthquake, damaging everything on the screen, although the earthquake momentarily pauses the game to perform the full animation, temporarily removing you from the action for four whole seconds.

Nigel also finds new armor, boots, and rings throughout his journey. Armor serves the sole purpose of allowing Nigel to tank more damage, and surprisingly, the armor slightly changes Nigel’s appearance, which is a nice touch for an adventure game from the ’90s; especially considering that some computer games, even several modern games – such as a certain game released on Thursday, June 22, 2023 – don’t have this feature, the hero forever doomed to wear the same odorous garments for eternity.

]

*the sword of gaia, earthquake doubles as time magic

]

*the sword of gaia, earthquake doubles as time magic

While armor does not provide magical effects, the boots and rings do – offering abilities such as healing-while-moving and immunity to floor hazards. Three out of the five pairs of boots protect Nigel from different floor hazards; however, in an odd decision likely inspired by development-time-restraints, most of these boots are found in the final dungeon. This is unfortunate, as immunity boots could have easily been utilized to add variety to the early-to-mid-game platforming and puzzles; but not too unfortunate, as swapping equipment requires going into the menu, briefly taking the player out of the action – a criticism commonly directed at The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time’s Water Temple dungeon, which also utilized iron boots in a similar menu-based fashion.

In addition to weapons, armor, and rings, there are various consumable items as well, serving different purposes such as healing and temporary power-ups. Nigel’s bag is capable of storing all consumable items, including dungeon keys, with a maximum capacity of nine for each item.

Consumables can be purchased from shops or found in treasure chests throughout the Island of Mercator, along with the prized non-consumable item: Life Stocks. Life Stocks serve as the primary means of increasing Nigel’s life points and function similarly to a certain game’s heart container system. They also enhance Nigel’s attack power, making them invaluable for progression. Fortunately, Life Stocks are the primary reward for puzzles, so you won’t be lacking during your time in Mercator.

Although there are several consumable items, only one truly matters in Landstalker; that is the strangely-named EkeEke grass.

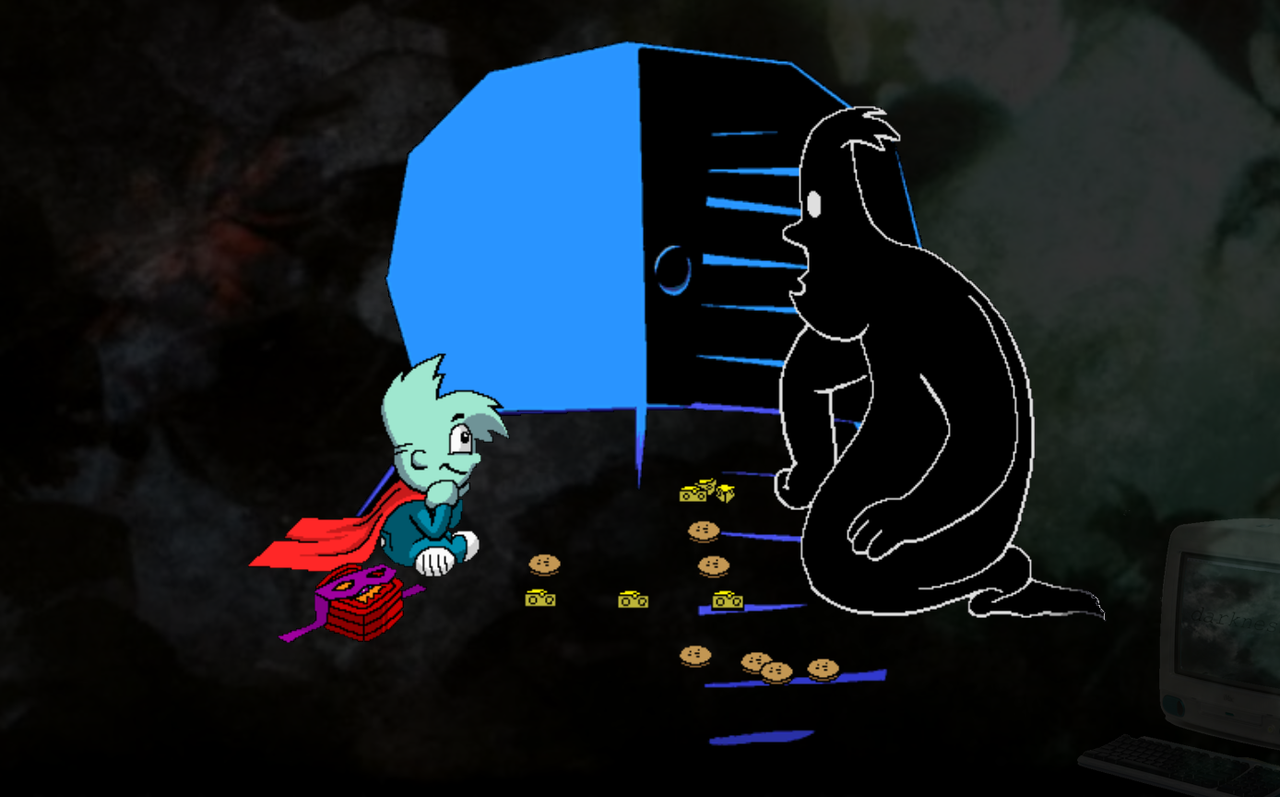

EkeEke grass serves a dual purpose: healing Nigel and reviving him from death. The idea is that Friday emerges from the bag and stuffs grass into Nigel’s mouth in the event that he falls in combat; resuscitating him and allowing him to continue his treasure hunting.

This feature functions as ‘extra lives’ and is integral to the Landstalker experience because death is as frequent and predictable as the sunrise, albeit lacking the beauty and tranquility of that celestial event.

*Friday reviving Nigel with EkeEke grass

*Friday reviving Nigel with EkeEke grass

While not immediately essential, EkeEke grass becomes incredibly crucial as the monsters grow more bothersome and the platforming becomes increasingly unfair. Leaving town without a full stock of nine grasses is a guaranteed waste of time since you will inevitably meet your demise and have to reload from your previous save.

Typing of which, Landstalker’s save system is very Dragon-Questian in that saving is only possible in a church through a priest who worships a Goddess. The priest even asks if you wish to continue playing once you have finished saving.

This method of saving functions as a checkpoint system, forcing you to reload at the last church upon true-death, courtesy of the Goddess’s benevolence. The underlying theory being that the Goddess governs time and space, summoning our hero back from the future to an earlier point in time, thereby facilitating the hero’s ultimate victory as long as the hero is willing to endure the time loop.

This checkpoint system ends up being a brutal cudgel that Landstalker hits you over the head with time and time again, especially when lacking EkeEke grass.

It’s safe to say that the revival properties of EkeEke grass were added late in the game’s playtesting after the developers received feedback that the playtesters were committing suicide en masse from having to redo hours of tedious platforming every time they fell into a pit of spikes, which – due to the game’s perspective – is completely unavoidable; so, instead of fixing the platforming issues they opted for giving the player extra lives.

Which is the perfect segue into why I will never play this game again.

V, CONCLUSION or: Reasons I Will Never Play This Game Again

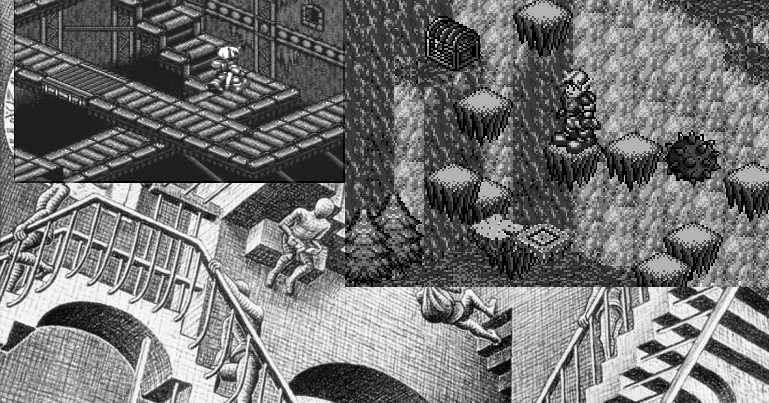

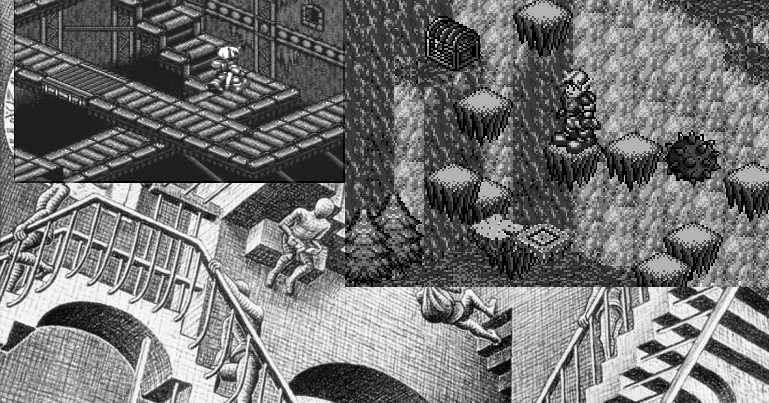

Landstalker’s manual claims that the game takes place on the Island of Mercator but, in reality, Mercator is part of M. C. Escher’s world of “Relativity,” full of unknown and incomprehensible geometries. Actively hostile toward everything and everyone within it, like a demonic puzzle box in which every wrong move flat-out kills you – this death is not immediate or sudden; it’s slow, deliberate and painful – like prolonged torture.

And like a cat, you have nine lives to experience this torture.

*Landstalker by M. C. Escher

*Landstalker by M. C. Escher

Like many computer games, Landstalker starts off relatively easy. A classic game design philosophy that has rarely ever been broken, slowly ramping up in difficulty around the half-way-point. This so-called “difficulty” is not really a matter of perspective – it is the perspective itself.

Monsters roam the halls; deadly traps litter the ceilings, waiting to crush you; and the floors sting with the sharp points of spikes. However, all of this is child’s play. The true enemy in Landstalker is the isometric perspective. The developers were well aware of this fact, utilizing the perspective like a ruler wielded by a 1940s teacher before laws against child abuse at school were instituted.

Landstalker feels like it’s purposely – and maliciously – designed to ruin the player’s day, utilizing devious tricks to deceive the player, all centered around exploiting the isometric perspective to fool the eye.

What you see is not true; it’s all lies. You may perceive an obvious platform to jump to, but as you leap, you find yourself plummeting into the pit below. In reality, the platform is situated on a plane slightly above you, an aspect impossible to discern without resorting to trial-and-error. Such jumps are scattered throughout every zone, sometimes occurring consecutively, which naturally prompts one to question the reality around them and, consequently, their own sanity.

*Perspective “puzzle”; sped up 3x; illustrating the absurd use of perspective to create mind-warping situations where the next jump is incomprehensible

*Perspective “puzzle”; sped up 3x; illustrating the absurd use of perspective to create mind-warping situations where the next jump is incomprehensible

This trial-and-error-platforming permeates your every pore. Within this hellish M. C. Escher painting simulator, you can never truly discern the placement of a platform. All you can do is leap and hope for the best. If you miss, you must climb back up and attempt a different direction, perhaps aiming for the platform this time – or perhaps not. Every jump is a gamble.

In comparison, computer games like Mario and Sonic present you with a clear playing field. The floating platforms in those titles require well-timed and precise jumps that, with enough skill, can be executed successfully on the first try. If you fail, it’s your own fault – just do better; however, this is not the case with Landstalker. Here, platforming becomes a series of mistakes, where successfully landing a jump on the first attempt is a feat achievable only after offering twelve sacrificial lambs on the dark altar of computer games.

In this way, Landstalker is a lot like Comcast Customer Support – it does not respect your time or sanity.

Picture this: your internet screws up, and you want to get back to doing your fun internet-things, so you call up Comcast Customer Support. The prompt says to press 1 to submit an issue; therefore, you press 1. It then asks you to describe your issue out of five different options, all with their own prompt. None of the options fit the exact nature of your problem, so you hit the 6th “other” option, thinking it will take you to a real person; however, for some mephistophelian reason, it loops you back to the start of the dialogue tree – forcing you to start over.

So, you start over; this time, frantically pressing prompts and saying “let me speak with a representative” repeatedly as if you just woke up inside a nasty – but warm – dumpster; before finally hearing the ringing noise of – possibly maybe – talking to a human being. Lo, hark and behold, a representative answers and asks what your problem is in the rudest tone imaginable; but you ignore this sleight; so desperate for resolution that you tell them your problem with an insane-looking smile behind the phone – “I’m getting a weird error message when I open the web browser.”

The Comcast representative gives you a fake apology; then, they say they have to put you on hold for a moment while they research your issue. At some point during this hold, the line drops, but the silence remains, and you don’t notice that you haven’t been on the line until five minutes have passed; they hung up.

Hands trembling in an alchemical mixture of rage and despair, you redial the Comcast Support line once again.

Eventually, after enough trial-and-error, your issue is resolved, and you’re back to playing cool online computer games; but at what cost? Yes, you got an $80 credit on your next internet bill, but the issue isn’t monetary – it’s cardiopulmonary.

*time to redo four rooms; the Comcast Customer Support experience

*time to redo four rooms; the Comcast Customer Support experience

In many dungeons – and sometimes the overworld itself – the platforming process is so lengthy that failing results in such a setback that you have to redo four to five whole rooms of insane-perspective-platforming just to get back to where you trial-and-errored to begin with just to trial-and-error again; eventually, after three hours of redoing rooms, you know the perspective-trickery so well that you have memorized every absurd jump needed throughout the entire dungeon.

Games like Landstalker are why re-releases and remasters of classic computer games have built-in save-state functionality; and while I played this on an emulator of sorts, I purposely did not use save-states to preserve the original experience of the game; but if I had, the game would have been completed in less than half the time due to the sheer amount of tedious retreading Landstalker makes you do upon every slight-failure.

Consider the following: you enter a room with a large-dark-pit separating yourself from the exit. There are a number of floating platforms you can hop across to reach the exit. If you fall, you land in a basement cellar full of monsters waiting to eat you, and if you happen to escape that cellar, you have to climb back up to the room you’re in now, having gone through several similar rooms along the way.

You go to jump on the first platform, which is – clearly – right in front of you, but you miss – because of the perspective nonsense – and fall into the pit. You take several hits from monsters in the cellar below but manage to escape and make your way back to the pit-room again fifteen minutes later; eventually, you make it across the pit, but only after repeating this process three additional times – but, alas, you’ve done it: you’re in the next room.

The next room has three doors. Two of these doors lead to new areas, maybe with treasure or a boss – whatever. The third door, for some bezelbubian reason, transports you back to the basement cellar with all the monsters. So, of course, you pick the wrong door – the cellar door – and you’re back in the basement, forced to escape, climb back up the numerous floors, through the pit-room – again – and back into the room with three doors. By this point – as it’s been ten minutes – you’ve forgotten which door you chose originally, so you accidentally choose the cellar door again, and again, and again.

That’s Landstalker.

That’s why EkeEke grass revives Nigel. Many of these little mistakes lead to eventual death by a thousand tiny cuts. If the revive system didn’t exist, you’d not only have to redo all those rooms you just completed, but you’d have to redo traveling there from the last church you saved at, completing any additional absurd platforming along the way.

Landstalker feels like it has a mind of its own, and that mind has one singular thought: “I hate you. Yes, you – the player.”

*moving platform puzzle, one mistake is spike pit into a redo into a heart attack

*moving platform puzzle, one mistake is spike pit into a redo into a heart attack

Landstalker is one of the most unique games for the Sega Genesis. An action-adventure game with an isometric perspective that is – mostly – a platformer at heart; unfortunately, Landstalker’s perspective undermines its core gameplay, and while movement is fluid, combat is “fun” – whatever that means – and the setting and characters are entertaining, this is not enough to make up for the hours of frustration that come from the tedious and often mean-spirited platforming sections that rely solely on you failing repeatedly before figuring out that “oh, the platform is actually above me to the left six degrees!”

Much of this frustration could have been alleviated if there was a rewarding pay-off; for example, you get a cool new ability when you complete a punishing platforming section; however, the most common treasure in this game is EkeEke grass – stuffed in every other chest – almost as if the developers knew you would need it for their own brutal and unfair game-design decisions. Nigel, outside of the Sword of Gaia, doesn’t feel like he’s getting stronger throughout the game, more just managing not to break his legs or impale himself on a spike.

Landstalker tries to reward the player with satisfaction alone, but that’s not enough. Successful completion of unfair platforming sections does not feel rewarding – it feels like a relief.

Landstalker does not require skill; it demands mindless repetition and therapy. And when the final boss was defeated, I felt relieved. I was finally free.

As always, if you don’t succeed – try again; or don’t. If you get bored, do something else.

(Originally published on 7/12/2023)

#ComputerGames #Landstalker #Review

*for a fleeting moment, I am the captain

*for a fleeting moment, I am the captain *the bridge of the Avalon-1

*the bridge of the Avalon-1 *Imagination interrupt: illusion has stopped responding.

*Imagination interrupt: illusion has stopped responding. *space sims: the origin; one of these things is not like the other

*space sims: the origin; one of these things is not like the other *a boy and his blog

*a boy and his blog *bottom screen on the left, top screen on the right; also claw.

*bottom screen on the left, top screen on the right; also claw. *keeps going and going and going and going and going and going

*keeps going and going and going and going and going and going *tetrominos falling into place; not at all a Radiohead experience

*tetrominos falling into place; not at all a Radiohead experience *the boy and the man

*the boy and the man

*digital landscape of The Boy circa 2001, authors: unknown

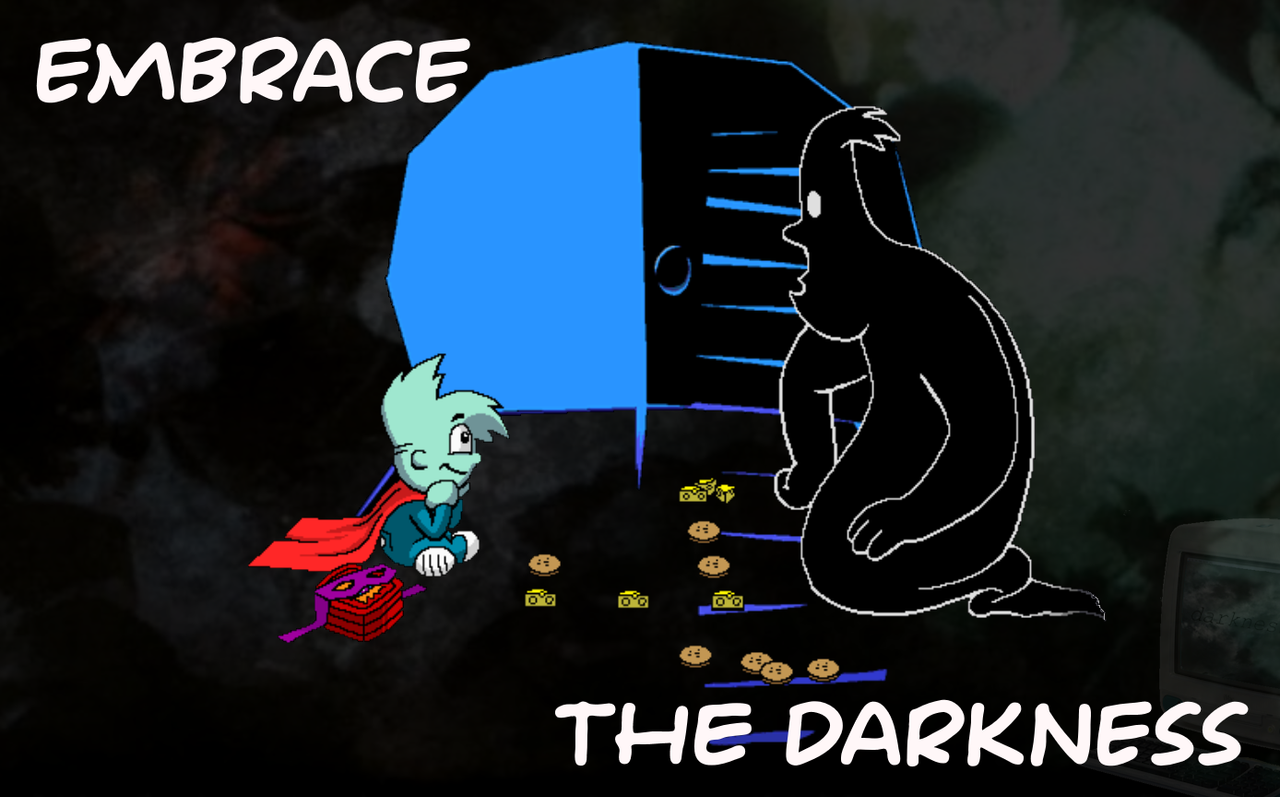

*digital landscape of The Boy circa 2001, authors: unknown *The Darkness we know so well; stepping through the fog of youth

*The Darkness we know so well; stepping through the fog of youth *ghosts of the past haunt The Boy overlooking suburban splendor

*ghosts of the past haunt The Boy overlooking suburban splendor *we can be heroes, just for one day.

*we can be heroes, just for one day. *Et in Arcadia, Pajama Sam

*Et in Arcadia, Pajama Sam *Pajama Sam captured by the trees in The Darkness

*Pajama Sam captured by the trees in The Darkness *clicking through youth

*clicking through youth *Sam confronts his fears

*Sam confronts his fears *Sam embracing The Darkness

*Sam embracing The Darkness

*can you spot all the references?

*can you spot all the references? *Shakedown, 1993

*Shakedown, 1993 *David Koresh, Kenji Orimo & Pockets, Alundra, and Jupiter

*David Koresh, Kenji Orimo & Pockets, Alundra, and Jupiter *Nintendo turns the Sega Genesis into a theme park with a $42.19 cost of admission

*Nintendo turns the Sega Genesis into a theme park with a $42.19 cost of admission *R06190; displaying Ranma ½ & Landstalker, prison cell number included

*R06190; displaying Ranma ½ & Landstalker, prison cell number included *the three elements that make this setup work: laptop, hdmi to rf modulator, R06190, and a Sega Saturn pad

*the three elements that make this setup work: laptop, hdmi to rf modulator, R06190, and a Sega Saturn pad *NA Landstalker, Doom, and JP Landstalker boxart compared

*NA Landstalker, Doom, and JP Landstalker boxart compared *Nigel and Friday, honeymooning on a raft

*Nigel and Friday, honeymooning on a raft *Island of Mercator, as pictured within the in-game map

*Island of Mercator, as pictured within the in-game map *Duke Mercator challenges Nigel

*Duke Mercator challenges Nigel *the bar, ever-present and never-ending – but why?

*the bar, ever-present and never-ending – but why? *part of the prologue, heavily compressed with every other frame removed

*part of the prologue, heavily compressed with every other frame removed *Saturn pad with crude paint drawings and official illustrations explaining the importance of diagonals

*Saturn pad with crude paint drawings and official illustrations explaining the importance of diagonals *Traveling the overworld; featuring phallic mushrooms and Nigel’s strut

*Traveling the overworld; featuring phallic mushrooms and Nigel’s strut *Landstalker gets creative with puzzles; button that moves statues, but you need to use Nigel’s head to ensure they move along the right path.

*Landstalker gets creative with puzzles; button that moves statues, but you need to use Nigel’s head to ensure they move along the right path. *never trust a man with a large statue of himself in his front yard

*never trust a man with a large statue of himself in his front yard *golem boss approaches!

*golem boss approaches! ]

*the sword of gaia, earthquake doubles as time magic

]

*the sword of gaia, earthquake doubles as time magic *Friday reviving Nigel with EkeEke grass

*Friday reviving Nigel with EkeEke grass *Landstalker by M. C. Escher

*Landstalker by M. C. Escher *Perspective “puzzle”; sped up 3x; illustrating the absurd use of perspective to create mind-warping situations where the next jump is incomprehensible

*Perspective “puzzle”; sped up 3x; illustrating the absurd use of perspective to create mind-warping situations where the next jump is incomprehensible *time to redo four rooms; the Comcast Customer Support experience

*time to redo four rooms; the Comcast Customer Support experience *moving platform puzzle, one mistake is spike pit into a redo into a heart attack

*moving platform puzzle, one mistake is spike pit into a redo into a heart attack

*Talk Talk’s “It’s My Life,” Popful Mail strategy guide mailer, old consoles; Breakfast Club backdrop

*Talk Talk’s “It’s My Life,” Popful Mail strategy guide mailer, old consoles; Breakfast Club backdrop *while the anime cutscenes are typically very few frames, they are all beautifully drawn and fully voiced in English thanks to Working Designs’ localization

*while the anime cutscenes are typically very few frames, they are all beautifully drawn and fully voiced in English thanks to Working Designs’ localization *NEC & Sega CD Popful Mail compared; Mail pictured in the same area in both, illustrating the near 1-to-1 level design between the two versions.

*NEC & Sega CD Popful Mail compared; Mail pictured in the same area in both, illustrating the near 1-to-1 level design between the two versions. *the various zones of Popful Mail; showcasing the Super Mario Bros. 3 inspired world map

*the various zones of Popful Mail; showcasing the Super Mario Bros. 3 inspired world map *Lina Inverse and Popful Mail; it’s up to the reader to figure out which is which

*Lina Inverse and Popful Mail; it’s up to the reader to figure out which is which *all three heroes in their spritely glory

*all three heroes in their spritely glory *goobers galore

*goobers galore *the various shopkeepers you will encounter on your popful journey

*the various shopkeepers you will encounter on your popful journey *it’s a platformer, I swear

*it’s a platformer, I swear *all three game over screens; something you’ll be seeing a lot

*all three game over screens; something you’ll be seeing a lot *Mail’s inventory screen; showcasing her armor, weapons and items

*Mail’s inventory screen; showcasing her armor, weapons and items *bosses, bosses, bosses!

*bosses, bosses, bosses! *end game credits

*end game credits

*Three Style Siff: Romancing SaGa concept art, mobile game sprite, and Minstrel Song concept art, respectively; the aesthetic difference in Minstrel Song being obvious (and ugly)

*Three Style Siff: Romancing SaGa concept art, mobile game sprite, and Minstrel Song concept art, respectively; the aesthetic difference in Minstrel Song being obvious (and ugly) *my thoughts exactly

*my thoughts exactly *Miyoo Mini Plus or Baby Arthur; which is more important?

*Miyoo Mini Plus or Baby Arthur; which is more important? *Well, which would you play first?

*Well, which would you play first? *the retro gamer council convening to revoke my membership

*the retro gamer council convening to revoke my membership *Can you spot the difference? I can’t

*Can you spot the difference? I can’t *David Bowie as the Goblin King, Kenji Ito, and David Sylvian of the 80s band Japan (respectively); all will become relevant in time.

*David Bowie as the Goblin King, Kenji Ito, and David Sylvian of the 80s band Japan (respectively); all will become relevant in time. *smiles and frowns; Kobayashi and Amano

*smiles and frowns; Kobayashi and Amano *Tomomi Kobayashi concept art compared to Kazuko Shibuya’s sprites; also Mime Bartz sprite from Final Fantasy V (bottom left) to illustrate just how similar both games look

*Tomomi Kobayashi concept art compared to Kazuko Shibuya’s sprites; also Mime Bartz sprite from Final Fantasy V (bottom left) to illustrate just how similar both games look *Final Fantasy IV, Romancing SaGa, and SaGa 2 compared

*Final Fantasy IV, Romancing SaGa, and SaGa 2 compared *two of many “hell zones”, areas you need to go highlighted in red; blocked up by monsters, each you will have to defeat, no exceptions.

*two of many “hell zones”, areas you need to go highlighted in red; blocked up by monsters, each you will have to defeat, no exceptions. *Red dragon battle; notice the characters lined up in rows and the awesome sprite work on the drago

*Red dragon battle; notice the characters lined up in rows and the awesome sprite work on the drago *skilling up after winning a battle; weapons skill up in the same way

*skilling up after winning a battle; weapons skill up in the same way *What happens when you get to the boss without any weapon skill uses left and a previous save file that would erase three hours of play; this boss took me 20+ reloads to defeat, finally getting lucky on the final try with a low-success rate 1-hit kill spell with 1 charge left.

*What happens when you get to the boss without any weapon skill uses left and a previous save file that would erase three hours of play; this boss took me 20+ reloads to defeat, finally getting lucky on the final try with a low-success rate 1-hit kill spell with 1 charge left. *boss at the top of the tower on the Island of Evil; climbs out the window shortly after this interaction

*boss at the top of the tower on the Island of Evil; climbs out the window shortly after this interaction *marked for death by the Assassin’s Guild, or something; kudos to Eien Ni Hen for the great translation work

*marked for death by the Assassin’s Guild, or something; kudos to Eien Ni Hen for the great translation work *Hmm, I wonder which option would award evil points?

*Hmm, I wonder which option would award evil points? *somehow Square captured the vaporwave aesthetic thirty years before its inception

*somehow Square captured the vaporwave aesthetic thirty years before its inception

*Penguin publishing cover art for William Gibson’s “Virtual Light”, SaGa 3 box art, Red from Gunstar Heroes and Haddaway’s “What is Love” single

*Penguin publishing cover art for William Gibson’s “Virtual Light”, SaGa 3 box art, Red from Gunstar Heroes and Haddaway’s “What is Love” single *out of respect for the brave souls messing with the 1s and 0s; full endgame credits roll for Final Fantasy Legend III, played upon defeating the final boss

*out of respect for the brave souls messing with the 1s and 0s; full endgame credits roll for Final Fantasy Legend III, played upon defeating the final boss *Marcel Duchamp Fountain, 1917; seminal work of “dada” art movement

*Marcel Duchamp Fountain, 1917; seminal work of “dada” art movement *cast of Chrono Trigger, drawn by Akira Toriyama; a much better cast of characters than those found in Final Fantasy Legend III

*cast of Chrono Trigger, drawn by Akira Toriyama; a much better cast of characters than those found in Final Fantasy Legend III *cast of Final Fantasy Legend III; Arthur, Curtis, Gloria, and Sharon, respectively; original concept art compared with Americanized NA manual art

*cast of Final Fantasy Legend III; Arthur, Curtis, Gloria, and Sharon, respectively; original concept art compared with Americanized NA manual art *Pureland Water Entity and world map of Final Fantasy Legend III, per the Game Boy manual; see the Pureland Water Entity in the far right

*Pureland Water Entity and world map of Final Fantasy Legend III, per the Game Boy manual; see the Pureland Water Entity in the far right *concept art of Talon found in Final Fantasy Legend III’s Game Boy manual; alongside Talon’s in-game sprite

*concept art of Talon found in Final Fantasy Legend III’s Game Boy manual; alongside Talon’s in-game sprite *the paradox begins

*the paradox begins *bootstrap paradox illustration created by yours truly

*bootstrap paradox illustration created by yours truly *crude illustration of the split timeline theory, preventing grandfather paradoxes

*crude illustration of the split timeline theory, preventing grandfather paradoxes *an example of an endless “one direction” door loop; still more interesting than Harry Styles; developers, don’t do this.

*an example of an endless “one direction” door loop; still more interesting than Harry Styles; developers, don’t do this. *a dungeon jumping puzzle that took me far too long to figure out

*a dungeon jumping puzzle that took me far too long to figure out *a battle scene; return to sea monke

*a battle scene; return to sea monke *Ashura, a recurring boss, with two Lizalfos from the Zelda series

*Ashura, a recurring boss, with two Lizalfos from the Zelda series *small collection of some of my favorite monster sprites: cat mummy, ronin, low-quality merman, Ghouls and Ghosts demon, and brain-in-a-vat-bro

*small collection of some of my favorite monster sprites: cat mummy, ronin, low-quality merman, Ghouls and Ghosts demon, and brain-in-a-vat-bro *dumb equipment UI: someone please explain what “Bronze” is referring to

*dumb equipment UI: someone please explain what “Bronze” is referring to *Dumb equipment UI: Someone please explain what “Bronze” is referring to

*Dumb equipment UI: Someone please explain what “Bronze” is referring to *Gloria, the mutant, casts Quake on a group of monsters, decimating them all; also meat

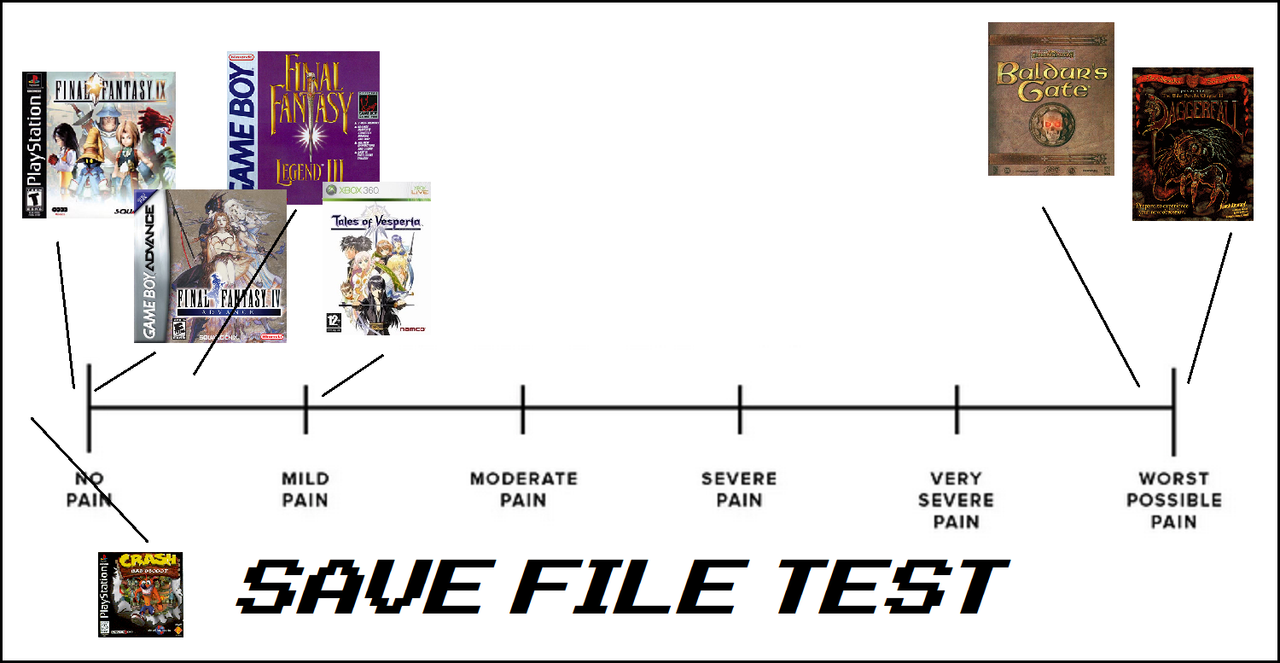

*Gloria, the mutant, casts Quake on a group of monsters, decimating them all; also meat *the save file test graph, simplified; ignore the “pain” bits (typo, seriously)

*the save file test graph, simplified; ignore the “pain” bits (typo, seriously) *Columbo trying to understand the hidden logic of Final Fantasy Legend III

*Columbo trying to understand the hidden logic of Final Fantasy Legend III *we did it! wait, what were we doing again?

*we did it! wait, what were we doing again?

*Sting, Japanese SaGa 2 box art, and Richard Dean Anderson

*Sting, Japanese SaGa 2 box art, and Richard Dean Anderson *Dungeon scene, notice the shadows on the columns and general sense of depth